Some of the most valuable sources of information for silent and early sound films can be found in Moving Picture World, Variety, and numerous other motion picture trade publications. Summaries of lost films, gossip about long-forgotten stars, thousands of movie reviews from critics and exhibitors, vintage ads that capture the zeitgeist of the era, and publicity stunts performed by local theater owners provide a window into the everyday machinations of the classic film industry from the most powerful studio head to the most rural theater owner.

Eric Hoyt’s Ink-Stained Hollywood tracks the evolution of these motion picture trade papers from their genesis in the early 1900s to the early sound era of the 1930s. Hoyt, the manager of the wonderful online resource The Media History Digital Library, uses his extensive knowledge of early trade papers to provide readers with context behind dozens of regional and national trade papers that document the film industry.

My favorite aspect of Hoyt’s analysis is his focus on how theater exhibitors used the various trade magazines. For instance, Exhibitor’s Herald ran a section called “What the Picture Did for Me” that ran film reviews submitted by theater owners throughout the country. One particular rural theater owner, Phillip Rand of Salmon, Idaho became a frequent and well-known contributor to the column.

As a publicity stunt, in 1923 Paramount flew Rand out to Hollywood and gave him a studio tour where he met stars like Viola Dana and Tom Mix. Photos of his tour appeared in the magazine to show that Exhibitor’s Herald had even the smallest theater owner’s interest in their hearts (Salmon, Idaho’s population was around 1,000 at the time). More importantly, this stunt was proof that people like Rand could benefit from a yearly subscription to the magazine.

Phillip Rand (left) meets with star Viola Dana (middle) and director George D. Baker (right) on his tour of Hollywood.

Hoyt examines the papers’ conflict of interest, trying to best serve the needs of the theater exhibitors while protecting the studio’s bottom line by advertising their films no matter the quality. It’s all too often when perusing through these magazines to find a large one-page ad and only a few pages away find a glowing review of the film. How could exhibitors trust a service that worked so closely with the studios? Of course, some magazines chose to more openly side with the studios and rely on their advertising money to stay profitable. Many smaller publications bragged about their independence as they offered no or limited ad space, charging higher prices for subscriptions hoping that exhibitors would pay a higher price to hear a perspective that aligned with their own.

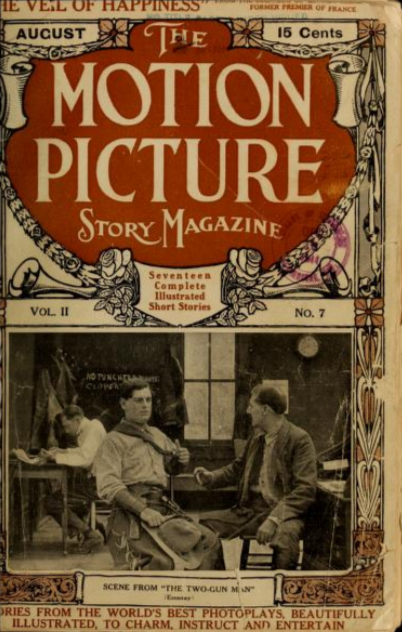

Hoyt’s writing is very academic in nature but he explains things well enough that you rarely have to reread sentences to get any of his analysis. Through an online version of the book, the appendix includes links to digitized trade papers, allowing you to check out the exact page and issue of each magazine that Hoyt uses as examples throughout the book. I must warn you though that each detour to a random issue of Motion Picture World will lead you down plenty of new rabbit holes. A positive in my opinion but it took me much longer to read than I originally expected. (Not to mention the many times I sought out a film from the advertisements that remain lost to time.)

One of the many magazines available to freely view on The Media History Digital Library.

A surprisingly recurring theme throughout Ink-Stained Hollywood is the evolution of censorship in Hollywood. Martin Quigley, a co-writer of the 1930 Production Code, was best known for creating Exhibitor’s Herald and held a lot of sway in the film industry in the 1920s and 1930s. Reviews from exhibitors routinely addressed whether a picture was clean to their standards and op-eds frequently proposed solutions to clean up Hollywood. That’s the advantage of tackling a topic so large over a brief period of time as there are bound to be topics and recurring themes that will grab your attention that you wouldn’t expect to find in such a book.

In the end, Hoyt’s Ink-Stained Hollywood provides a much-needed road map to understand the differences between each magazine and the context that they were published and consumed under. Hoyt convincingly proves his thesis that “the millions of pages published by the American film industry’s trade press [are] among Hollywood’s greatest productions”.

Instead of just looking up quick reviews and perusing through vintage ads, having read Hoyt’s book I have much more context to understand how these papers reflect the struggles and landscape of early film. If you enjoy perusing early Hollywood magazines and want to learn more about them and how they impacted Hollywood, then Ink-Stained Hollywood is a must-read.

This book review is part of the 2022 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge hosted by Raquel Stecher’s Out of the Past blog. Check out my other reviews of classic film books I am reviewing this summer and great reviews from others.

This is right up my alley! Thanks for your review.