I recently finished Buster Keaton’s silent filmography—or so I thought. Focused on watching all Keaton’s appearances in Arbuckle shorts, the 21 shorts he directed, and his silent feature comedies, I overlooked his starring role in Herbert Blanche’s 1920 The Saphead.

It was a natural mistake—and one I quickly remedied by watching it online. A light-hearted drama with a few bits of comedy, The Saphead has largely been forgotten in favor of Buster’s independently produced films he had full control over. Even if the film doesn’t have the same ingenuity and charm as Buster’s later films, it contains a fascinating look into Buster’s rise in the public conscience in the early 1920s and his evolution as a performer.

Buster Keaton as Bertie the Lamb in 1920’s The Saphead.

Keaton Going Solo

By 1919, Keaton had become known as Roscoe Arbuckle’s sidekick, appearing in fourteen two-reel comedies alongside one of the biggest stars of the late 1910s. 1920 saw them part ways. Arbuckle, with a new million-dollar-a-year contract in hand, went to make feature films for Paramount. Keaton, backed by future brother-in-law Joseph M. Schenck, began work with his own production unit assigned to make roughly eight two-reel comedies a year.

Many comedians came and went in the silent era with numerous production units churning out a dozen or so one or two-reel comedies that would never fully connect with audiences. Keaton’s first few comedies would be important ones to land with the public to keep his screen career on its upward trajectory. But before he could fully commit to his solo debut, Schenk loaned him out to Metro to play the lead in The Saphead.

Adapted from the hit 1913 Broadway play The New Henrietta, the film was originally meant to star Douglas Fairbanks. Having originated the role on Broadway, Fairbanks already made an adaptation in 1915 The Lamb that featured his motion picture debut. Busy with other projects, Fairbanks suggested they cast Keaton in the lead role instead.

Promotional material for 1915’s The Lamb (left) and 1920’s The Saphead (right) sans Buster Keaton’s character.

With hindsight knowing his future career, replacing Fairbanks with Keaton seems like an odd choice. Other than the two performers’ gifted physical performances and unique onscreen charisma and appeal, Fairbanks’ adventuring, optimistic go-getter persona couldn’t seem farther away from Keaton’s expressionless Great Stone Face. On the heel of Keaton’s work with Arbuckle, which features Keaton running maniacally around while cracking plenty of smiles that he rarely uses in his later works, the decision to call up Keaton in Fairbanks’ place becomes much more plausible.

Whatever Fairbanks saw in Keaton to fill the role he made famous, Metro agreed to give Buster his shot.

Bertie the Saphead

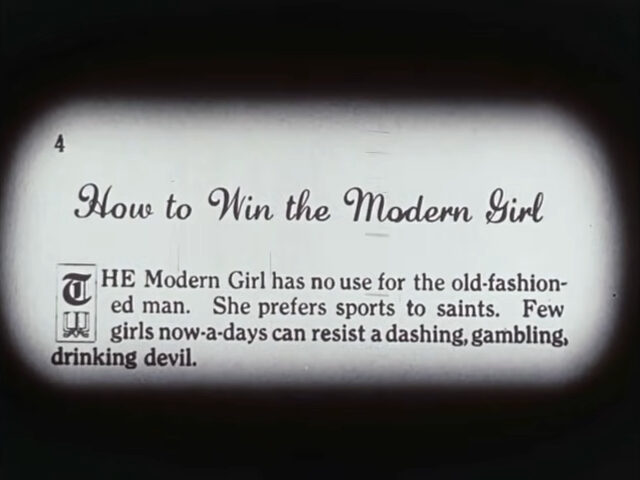

The Saphead follows our titular character Bertie Van Alstyne (Buster Keaton) who incurs the wrath of his rich stock-trading father Nicolas (William H. Crane) after months of staying out late partying on the town. Bertie, normally a calm-natured soul, has only been pretending to be a haughty socialite. Following the advice of a hokey self-help book that asserts the modern girl is only interested in the partying type, Bertie reaches for party-boy status to gain the attention of his love Agnes (Belulah Booker).

Eventually, Bertie and Agnes communicate their feelings to each other but not before Bertie’s father disowns him for his partying ways. Now on the outskirts of his family, Bertie must work his way back into his father’s good graces to gain his permission to marry Agnes. Add in a family scandal and a conniving brother-in-law trying to take over Nicolas’ stocks on Wall Street and you got yourself a comedic drama.

Bertie falls for crappy love advice hook, line, and sinker.

While Keaton certainly employs the same light and largely deadpan mannerisms that he’s known for today, Bertie is not the self-made man Keaton would play in his later self-produced films. Bertie is a dolt. Even when triumphant, he bumbles his way back into success by sheer dumb luck.

Of course, some humor can be found in a simple fool. For instance, one scene features Keaton attempting to get arrested in a speakeasy hoping to further his sexy bad boy image for Agnes. After trying several ways to stand out from the cops during their raid of the bar, Bertie hands a cop a bill in hopes of buying him a ride in the back of the cop car. Instead, the cop accepts the bill as a bribe leaving a despondent Bertie to return home rather than gain his nortoriety in the gossip collum.

A police officer takes Bertie’s money but not him.

While later Keaton characters would triumph by crafting an ingenious machine or crafting a plan that ends up working in an unexpected way, Bertie stumbles his way into success without any effort on his part. For instance, in the climax, Bertie unknowingly saves the day by buying up his father’s plummeting stock when one of his aids bids him to. His father is ecstatic but we the audience are left feeling no suspense or excitement.

Perhaps the story could have worked better with a naive, go-getter that Fairbanks would have provided. The finished product however is filled with flat-stock characters that fail to deliver on the film’s conflict and humor; there’s no one to root for or even care for.

Perhaps it’s unfair to compare The Saphead to Buster’s later genius. It’s by no means a slog to get through, with a couple of interesting gags and jokes, but it still stands as a middling film that’s an awkward fit for Keaton’s persona. Far more interesting than the film itself is how it plays into Buster’s early career and screen image.

The opening title card putting Broadway stage veteran on the same billing as a budding screen presence.

Reviewers Hail Buster Keaton

Initially, the biggest name in the film was the well-respected stage veteran William H. Crane who originated the role on Broadway. In promotional materials, Crane and Keaton shared equal billing. Upon the release of the film, there was no disagreement about who was the star of the film. Nearly every critic agreed that Keaton stood out above the whole cast. A January Motion Picture News article simply titled REVIEWERS HAIL BUSTER KEATON listed the following praises:

He invested the part with scores of really fine touches of kindly satire and pathos, as well as of nicely balanced comedy.

The youngest star of filmdon [Keaton] is destined to win a high place in the esteem of the picture goers.

Buster Keaton makes his bow to the cinema world in a seven-reeler…being so auspicious that the thoroughness of preparation for stardom is indicative of the fine traditions he is following in his acting.

Motion Picture News Jan. 15, 1921

Keaton’s praise shines through even in the most tepid reviews of the film. Wid’s Daily complains about the long pauses between laughter while Variety calls out the film’s overreliance on long shots and several scenes with poor lighting; yet, both remained effervescent in their notices of Keaton. Wid’s Daily remarks that Keaton carried the picture so much that you could feel his absence when he did not appear in a scene. Variety called Buster a revelation, “the personification of a mental minus sign in facial expression”.

One of several pratfalls that shows off Keaton’s physical comedy.

Even if the material didn’t quite mesh with Buster’s persona Keaton added the most as he possibly could to the character. He added a few of his signature pratfalls into the mostly situational comedic drama that elicited plenty of laughter from audiences and praise from critics.

While The Saphead was originally planned to be released in September of 1920, a slight delay landed its premiere on October 18th. By this time, Keaton had already released his two-reel comedies One Week and Convict 13. Metro, releasing his two-reel comedies, had plenty of reason to push Keaton’s name and face in the fall of 1920.

Several theaters took the opportunity to screen a Keaton short before playing The Saphead. Motion Picture News reported that two New York theaters ran the newly released The Scarecrow in front of The Saphead to a full house. People were clearly clamoring for Keaton just as much as the critics were in his first foray as a star into pictures.

A July 1920 Moving Picture World snippet promoting Keaton alongside several of the day’s stars.

Just the Beginning…

Keaton—and Metro for that matter—couldn’t have planned his onscreen coming out part any better. Gaining acclaim in a feature film not only provided added publicity but also reached audiences less inclined to watch comedy shorts. Keaton also had proof he could succeed in a feature film when he transitioned from two-reelers to features just a couple of years later with Three Ages.

Without The Saphead would Buster still have broken through and had such a unique career? Almost certainly. But his first feature film role definitely made his star shoot higher and much faster propelling him into the most proficient and rich decade of his career.

The Saphead gave audiences just a glimpse of what was to come in Buster’s career. Keaton’s over two decades of experience dating back to his childhood years on the vaudeville stage had built up to unveiling the proto-type of his Great Stone Face character. A New York Times review written about his work in The Saphead could very well have been written by a number of his latter silent features:

Keaton is a natural screen comedian, a pantomimist.., and although he always remains solemn, he is defnitely subtly expressive, revealing many shade of subjective tragedy that are ridiculously comic from the oustide point of view. And the case with which he plays gives his perfromance the finish that pure comedy, even extravagantly absurd comedy, requires. He many not have great versatility—that remains to be seen—but within the field is one of a unique group of screen players… an accomplished and peculiar clown, and therefore a gentelment of comedy.

New York Times Feb. 14, 1921

If only they knew what lay ahead for the great Buster Keaton.

This blog post is a part of Silentology‘s Tenth Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon. For more great articles celebrating the seminal work and career of Buster Keaton, visit the blogathon’s main page.

I’ve seen The Saphead twice. It’s not a great film and I doubt it would be remembered at all were Keaton not in the cast, but it’s charming for what it is. You’re absolutely right that this film was not essential to Keaton’s developing career, but it did give audiences a foretaste of one of Keaton’s familiar character types, the spoiled rich young man who becomes a hero. He would make the heroism much more active and less dependent on chance or bumbling, of course, but Bertie is in many ways the ancestor of Rollo Treadway and Alfred Butler.

Thanks for sharing critics’ reviews of The Saphead. It’s interesting to see how the film was received Back in the Day.

I had read about The Saphead for many years before I saw it. Most books said it wasn’t anything special. I was surprised when I finally saw it that it wasn’t bad, and that Buster’s performance was wonderful. It reminded me of The Front, where Woody Allen played in a movie that he didn’t direct. I felt that the pacing was off. One other thing, Many books said The Lamb was adapted from The New Henrietta, but it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the story, except that the hero is nicknamed The Lamb.

Ah the makes sense. From what I read it looked like The Saphead was a modern updating of the two Henrietta play adpatations from the 1887 and 1913 stagings but alas I couldn’t find an accessible print of the 1915 The Lamb to compare for myself.