Last year I enjoyed reading Zane Grey’s most influential and frequently adapted for the screen Western Riders of the Purple Sage. This year I read Grey’s first Western novel the 1910 Heritage of the Desert and watched a couple of 1930s B-Western adaptations.

The novel begins when a group of Mormon cowboys stumbles upon an almost dead hired hand named John Hare, a Connecticutian traveler attacked when mistaken for a spy by a rival rancher. Nursed back to health, Hare quickly becomes friends with the Mormon patriarch August Naab and falls in love with his half-daughter Mescal even though she is betrothed to become another man’s second wife. Hare quickly becomes involved in Naab’s fight against the rancher Holderness who is pressuring Naab to give up his land and water rights.

It’s a pretty standard plot for the Western genre. Forbidden love, fights over land, an honest group of cowboys pitted against an outfit of gunslinging outlaws. Grey, however, is quite adept at both painting vivid images of the Western frontier and crafting unique characters. He peppers his novel with beautiful descriptives of the Utah desert, significantly elevating this otherwise by-the-numbers plot that hundreds of novels would imitate over the ensuing decades. For instance, when John Hare gets his first glimpse of a Southern Utah valley, Grey beautifully writes:

He saw a red world. His eyes seemed bathed in blood. Red scaly ground, bare of vegetation, sloped down, down, far down to a vast irregular rent in the earth, which zigzagged through the plain beneath. To the right it bent its crooked way under the brow of a black-timbered plateau; to the left it straightened its angles to find a V-shaped vent in the wall, now uplifted to a mountain range. Beyond this earth-riven line lay something vast and illimitable, a far-reaching vision of white wastes, of purple plains, of low mesas lost in distance. It was the shimmering dust-veiled desert.

Alongside his vivid descriptions of the desert landscape, Grey’s three-dimensional characters keep you invested even when the story slows down a bit. Although he had very little firsthand knowledge of how Mormons lived in the 1870s, he manages to paint a nuanced picture especially compared to the majority of novels and films from the time period that merely painted Mormons as cartoony villains. He doesn’t shy away from depicting polygamy, even having Mescal being pared off to become a polygamous wife; yet, through the pacificist character of August Naab, Grey humanizes his Mormon characters without skirting around the controversies of the faith community (much in the way John Ford would do years later in his severely underrated Wagon Master).

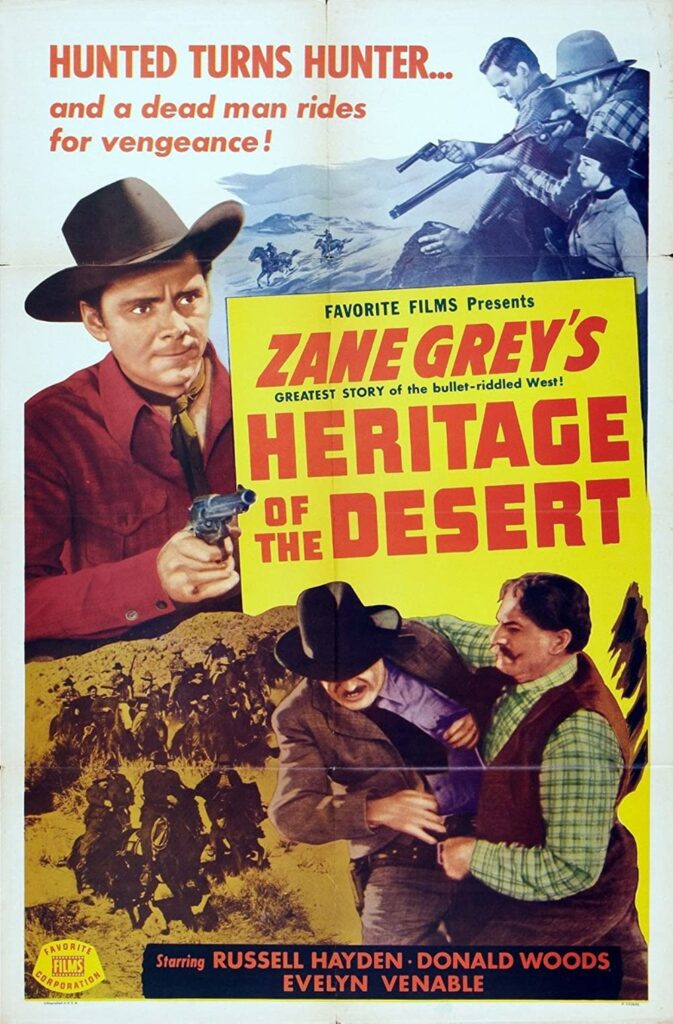

The book was adapted for the screen three times: in 1924 by Irvin Willat, in 1932 by Henry Hathaway in his feature film debut, and in 1939 by Lesley Selander. The 1924 version survives unavailable for viewing in the Gosfilmomond archive. It’s a shame because my personal favorite Ernest Torrance plays the juicy role of August Naab alongside Bebe Daniels as the female lead. Motion Picture World, while not impressed by the plot, praised Ernest Torrence for giving “a splendid performance, adequately suggesting the greatness of character and the vision of the pioneer”. Being in the shadow of Paramount’s 1923 widely successful box office behemoth western The Covered Wagon, it apparently was given the budget of an A-picture that allowed some beautiful on-location shooting.

Advertisements for the three screen adaptations of Heritage of the Desert: 1924 (top left), 1932 (bottom left), 1939 (right).

Unfortunately in the two available screen adaptations, many of the strengths of Grey’s writing are not transferred to screen. Both B-Westerns struggle to recreate Grey’s beautiful imagery onscreen without a large budget or unique cinematic vision. The 1932 version, starring a fun David Landau as the ruthless Holderness and Randolph Scott in his first Western, does a decent job of sticking to the novel in its under-hour running time but mishandles a sped-up, climactic ending. The 1939 version works as a fast-paced B-western but fails as a faithful adaptation of the novel, adding more shootouts and plot twists to spice up the action. In both, there is no mention of Mormons, although the 1939 version gives Naab some vague religiosity that tries to explain his hesitancy to confront his rival Holderness.

While I preferred the more action-packed Riders of the Purple Sage (both the novel and its film adaptations), Heritage of the Desert is a worthy entry into the Western genre and clearly had a lasting impact on the genre in novels and films. It is quite impressive that despite the fact that in 1910 most films were short two to three reels, Grey’s novel reads like it was made for feature films, especially his climactic shootout to save the girl from the villain’s grasp. Fans of Westerns will enjoy the breezy novel and, if they are up to watching poor versions on a free video site that shall not be named, will enjoy watching its two under 80-minute B-westerns adaptations.

This book review is part of the 2022 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge hosted by Raquel Stecher’s Out of the Past blog. Check out my other classic film book reviews and others’ great reviews.

Just curious! Naab is a very unusual name. I wonder where Zane Grey got the name because my grandfather, John Peter Naab homesteaded in Fruitland, Duchense, Utah during the time the book was written and I’ve read Zane Grey was in the area. Was it possible they knew each other? Most people misspell the name Naab, so for Zane Grey to use the exact spelling in his book makes me curious. Also, my grandfather’s parents were baptized Mormon but I’ve not found that my grandfather was.

That’s a fascinating connection! I wasn’t familiar with the Naab name and it’s cool he actually spelled it right. I recently came across a YouTube great video where a historian tracks Grey’s early exposure to Mormons that would be a good resource for you.

If I recall correctly Grey based the character of August Naab largely on polygamist Jim Bennett who he meet during trips in 1907 and 1908 in the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. I know Grey returned later to Northern Arizona and Southern Utah but I don’t know if he would have gone as north as Duchense. Are there any Naab’s that would have lived further south around that time? Grey definitely had experience in Kanab before writing Heritage of the Desert so my guess would be he might of heard the name from somewhere around there.