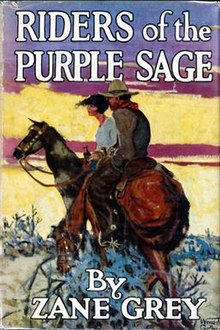

Ohio-born author Zane Grey, originally a dentist and minor league baseball player before trying his hand at writing, was instrumental in solidifying the major themes, characters, and tropes of the American Western genre. Writing dozens of novels and short stories from the first decade of the 20th century until his death in 1939, Grey also heavily influenced the depiction of the old west in Hollywood. Dozens of his novels were adapted into over a hundred films with the majority of them being made in the 1930s and 1940s. For a short time period, Grey even created his own production studio to better control the film adaptations of his works.

To explore how Grey’s vision of the West influenced classic Hollywood filmmakers, I decided to read his most commercially successful novel and the first one adapted into a film: 1912’s Riders of the Purple Sage. Set in the fictional Mormon town of Cottonwood, Utah in 1871, the novel follows Jane Withersteen’s quest to defend her large tract of land from conniving cattle rustlers and the abusive Mormon leaders in her own community. Having grown up Mormon myself and having spent a considerable amount of time in Utah throughout my life, I thought it would be a fascinating read. Also, the book has been adapted into five motion pictures giving me plenty of opportunities to see how Grey’s prose was adapted for the big screen over several decades.

The novel begins when Lassiter, a mysterious, black-clad gunman searching for his sister who disappeared 18 years ago, shows up at the Withersteen ranch. The unmarried Mormon Jane Withersteen, who controls large herds of cattle and a sizable tract of land inherited from her father, is being pressured into a polygamous marriage with the town’s stern Elder Tull that would result in her giving up her land, livestock, and independence to her husband and the church. Needing protection and always friendly to outsiders, Jane welcomes Lassiter into her home despite his reputation in the area as a cold-bolded killer much to the chagrin of the local Mormon clergy.

Shortly after Lassiter’s arrival in Cottonwoods, Tull teams up with the castle rustler Oldring and his infamous Masked Rider to steal a herd of Jane’s cattle to imitate her into becoming his third wife. Jane sends her trusted cattle hand Venters to face Oldring and retrieve her cattle. In a face-off, Venters shoots Oldring’s notorious Masked Rider only to find out the rider is a young woman. While Venters nurses the Masked Rider back to health in a secret hideout in the canyon, at Withersteen Ranch Jane and Lassiter start falling in love as they take in a little orphan named Fay. Soon Lassiter discovers that Jane’s friend Bishop Dyer was the one responsible for his sister’s death. Jane hopes to prevent Lassiter from enacting revenge while struggling to overcome her own guilt of failing her religious duty to marry a Mormon.

Once Venters has fallen in love with and nursed Bessie the Masked Rider back to health, he returns to Withersteen’s ranch to fend off an incoming attack from Tull and his castle rustlers. Will Jane keep her ranch and autonomous position in her community? Will Lassiter avenge his sisters’ death and carry out his revenge on Bishop Dyer and the elders of Cottonwood? Will Jane, Lassiter, Venters, and Bessie survive Tull and Oldring’s raid and make it out of Cottonwood alive? I guess you’ll just have to read the novel to find out!

On the surface, the story is a melodramatic dime novel filled with Western stock characters: the mysterious gunman, the compromised female romantic interest in need of protection, the power-greedy villain willing to use whatever means necessary to keep control over his town. These stock characters seem like easy characters to plop into any Western story and easily put onscreen. Beneath this simplicity, however, is much more depth and darkness. Each character’s internal conflict heavily influences the narrative of the story.

For instance, Jane Withersteen struggles to stay true to her community’s religious beliefs while maintaining her independence in a patriarchal abusive system. In the end, Jane resolves this internal conflict by keeping her personal faith in God while rejecting the misogynistic dictates of her Mormon elders. Lassiter similarly must find the balance not in a religious philosophy but in his own internal creed of revenge and bloodshed. By the conclusion of the story, Lassiter successfully balances his propensity to fight with his responsibility to protect the love he has for Jane. Grey, not known for historical accuracy, uses the background of Mormon and non-Mormon antagonism in the 1870s to explore themes of masculinity, violence, and faith.

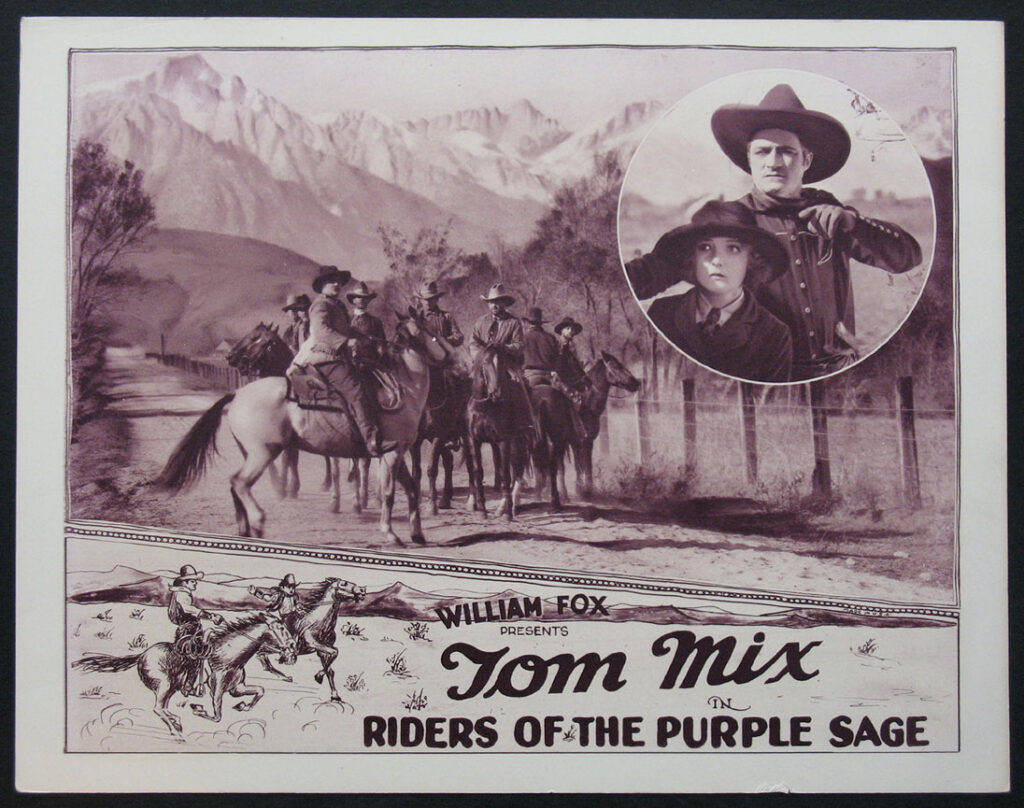

A film poster for the 1925 adaptation of Riders of the Purple Sage starring Tom Mix.

When many mistakenly attribute a film like The Searchers as the first Western to deal with darker themes, Grey’s works like Riders of the Purple Sage show that the Western genre has always been a fruitful place to investigate complex ideologies, modern definitions of manhood and gender, and the American myth itself. In a time when the Western was becoming a staple in American film, Grey’s vision of the West foreshadowed where filmmakers would take the genre over the coming years. For example, Lassiter resembles the rough and tumble Western gunslingers with a heart of gold that William S. Hart would play throughout his career in the silents in films like The Bargain or Hell’s Hinges.

Riders of the Purple Sage itself was adapted into a now-lost film by the Fox film corporation starring William Farnum and directed by Frank Lloyd in 1918. I’ve recently watched the 1925 Tom Mix version and am currently hunting down the 1931, 1941, and 1996 versions and will write about my thoughts on the adaptations sometime in the future. Most of the films excluding the lost 1918 and 1996 adaptations, jettison the Mormon themes and turn the villain into a more generic judge hoping to increase his power in Cottonwood. The 1925 Tom Mix version I watched worked fine as a B-western but misses the gravitas of the novel without the complexity of Jane’s faith and the Mormon/Gentile conflict.

Over a hundred years after its publication, Riders of the Purple Sage is a perfect showcase of Zane Grey’s engrossing Western melodramas and the picture of the American West that heavily influenced early Western films. Grey manages to weave melodramatic romance, complex religious and moral quandaries, and beautiful descriptions of the American West. I’d particularly recommend the novel to fans of pulp dime novels, Western junkies, or anyone wanting to better understand the development of the myth of the American West that captured the imagination of millions of Americans on the printed page and on the silver screen.

This book review is part of the 2021 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge hosted by Raquel Stecher’s Out of the Past blog. Check out all my classic film book reviews and great reviews from others participating in this summer’s challenge.

Sounds like the most recent version with Ed Harris and Amy Madigan was fairly true to the novel, at least by keeping the Mormon underpinnings…