The canon of the greatest films constantly changes as each generation reevaluates yesteryear’s classics and rediscovers previously overlooked films. Oftentimes, films held in the highest esteem by contemporary audiences and critics do not become beloved by later generations. Evolving morals, changing tastes, and decades of hindsight slowly chip away at the status of many once-great films, reducing them to aged artifacts of the filmmaking styles of the day. (Stay tuned for next month’s 2022 Sight and Sound Poll to see this happen in real time.)

For some of the earliest great films, however, the films themselves do not even survive for later critics and audiences to reevaluate. This was the fate of George Loane Tucker’s 1919 film The Miracle Man which today has no known surviving copies. When rattling off the greatest hits of a begone silent era, critics of the early 1930s routinely cited The Miracle Man alongside films like The Covered Wagon, The Big Parade, and *sigh* The Birth of a Nation as the greatest heights of cinematic artistic achievement. (For one example see this article in April 1932’s Motion Picture Herald.)

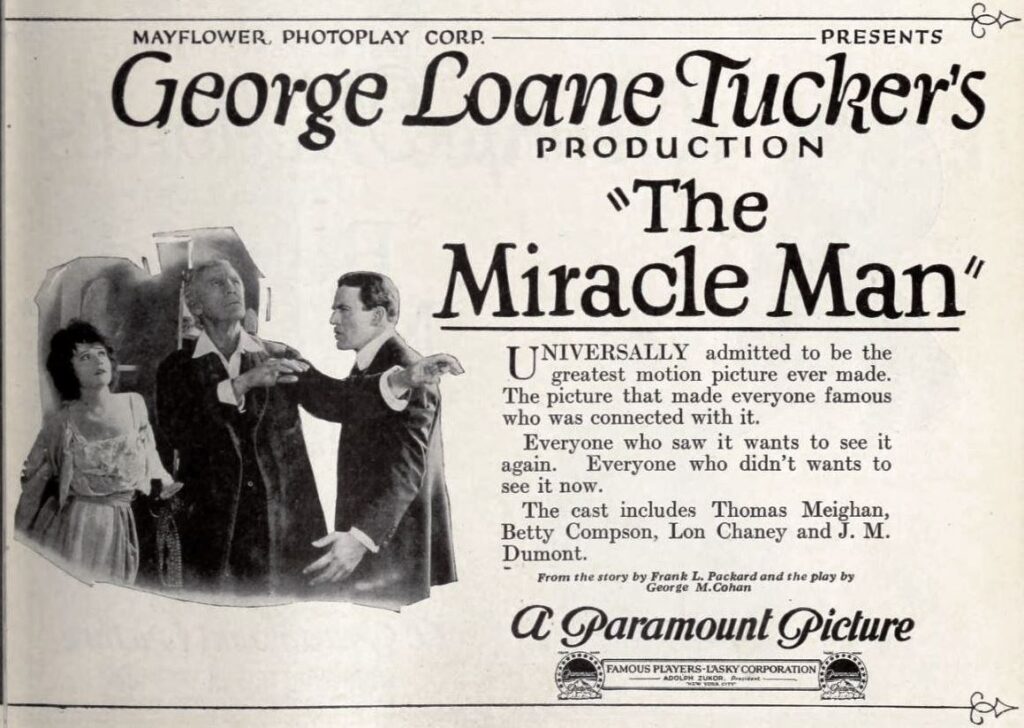

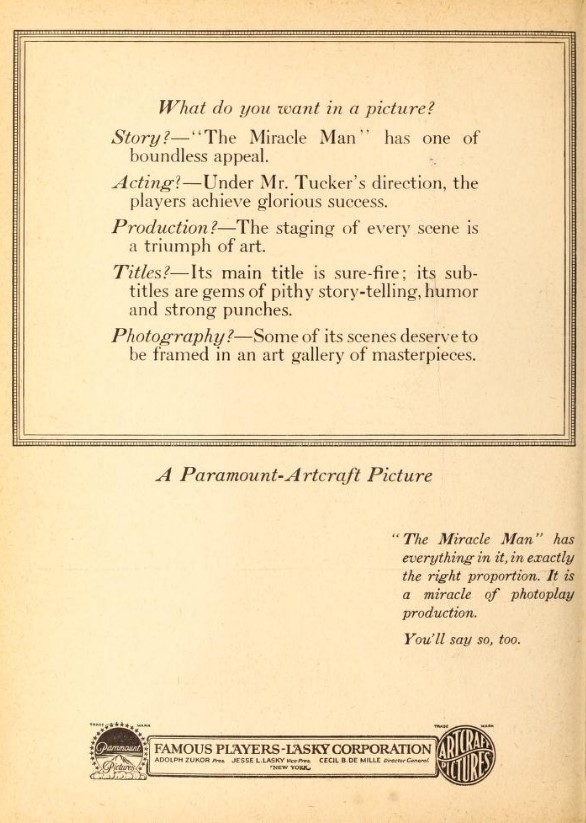

A lobby card for The Miracle Man (1919).

Fortunately for us, we do have some idea of what The Miracle Man was like. The 1914 novel of the same name is easily available to read online. Roughly two minutes from the film survive, highlighting the most discussed scene from the film. Most importantly, Norman Z. McLeod directed a 1932 sound remake heavily influenced by the original. By examining the surviving footage and the precode remake, we can start to piece together a better picture of the lost classic The Miracle Man and find out if we have a great film in the 1932 remake.

This review of the lost 1919 silent and 1932 sound versions of The Miracle Man is a part of Hometowns to Hollywood‘s Take Two! Blogathon. Make sure to check out other great posts about Hollywood remakes.

A Lost Instant Classic

Frank L. Packard’s 1914 novel The Miracle Man follows a group of four New York cons who hatch an embezzlement scheme centered on publicizing a small-town faith healer. Their plans quickly go awry when the faith healer miraculously heals a crippled boy, forcing them to reconsider their scheme, relationships, and life of crime.

The book proved to be a sensation when it was released in 1914. By the end of the same year, George M. Cohan directed a Broadway play based on the novel. Famous Players Lasky paid $25,000 for the rights to Cohan’s play hoping to produce it as a star vehicle for actor Thomas Meighan.

To act alongside Meighan, the studio selected Bette Compson, a regular in Al Christie comedies, and Lon Chaney, a character actor slowly rising through the ranks. George Loane Tucker, best known for his scandalous white slavery 1913 feature film Traffic in Souls, helmed the direction of the picture.

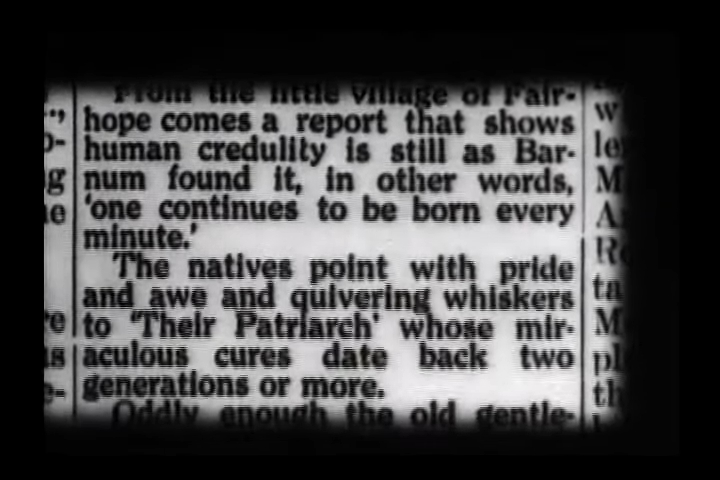

Using the novel and critics’ brief synopses, we have a pretty complete picture of the film’s plot. The film begins in Chinatown as Rose a fake streetwalker, the Frog a contortionist, The Dope a fake pimp, and the leader of the outfit Tom Burke grift local tourists in a New York cabaret. Hoping to cash in on a big score, Doc hatches a plan centered on a blind and deaf small-town faith healer he read about in the paper.

The plan is rather simple. Fake a miracle, publicize it, and manage the Patriarch’s business expenses, taking naive believers’ generous donations and keeping it for themselves. The Frog will use his contortionist skills to fake a miraculous healing, Rose will get close to the Patriarch posing as his long-lost grand-niece, and Doc and the Dope will drum up publicity, making sure as many people as possible will be there to witness the miracle man ‘heal’ the Frog.

A snippet in the paper where Tom discovers his next big score.

Initially, the scheme goes perfectly. Rose’s disguise allows her and Tom to get close to the nearly blind and deaf faith healer. The Frog and Harry gather a group of curious train passengers, including two journalists and a band of believers, to come see the miracle man heal The Frog’s crippled frame. With his audience, the Frog crawls toward the Patriarch and slowly relaxes his contorted body, wowing the crowd.

Unfortunately for the gang, amongst the crowd is a local crippled town boy whose disbelieving father had barred him from seeing the faith healer. Following The Frog’s example, the boy hurriedly limps toward the Patriarch. His crutches fall as he runs up to the Patriarch and hugs him. Claire, a rich paralyzed woman, stands up from her wheelchair, confirming that the boy’s healing was no hoax either. A stunned and speechless crowd aren’t in as much shock as the gang now confronted with a moral dilemma.

Following the very real miracle, the gang falls apart as one by one they decide to get out of Tom’s plan and their life of crime. Claire’s brother Richard begins courting Rose, the Dope falls in love with a local town girl, and the Frog becomes the adoptive son of an old woman in the town who recently lost her only son. Tom is the last holdout, taking charge of the Patriarch’s finances and pocketing the donations believers give him to help build a chapel for the faith healer.

After Rose turns down Richard’s marriage proposal out of her love for Tom, Tom gives up his scheme and reconciles with Rose. Now upright, reformed citizens of the small town, the four former criminals gather to pay their respects to the elderly Patriarch. The miracle man dies peacefully surrounded by the gang as they commit to continuing the Patriach’s mission of preaching goodness.

(For a more comprehensive recreation of the film, see this post by Criticreatro who uses synopses in Brazilian film magazines from the time to describe the lost film’s complete plot.)

Two minutes of the film managed to survive as part of Paramount’s 1933 promotional film The House that Shadows Built celebrating the studio’s greatest achievements of its first twenty years. It too often seems that the fragments of lost films that survive are rather perfunctory in nature but luckily for us, Paramount’s showboating preserved the most discussed scene of the film: the faith healer’s successful miracle.

This brief scene shows off Tucker’s experienced directorial style. The camera places us in the viewpoint of the crowd gathered to watch as Chaney’s character drags himself up a dirt path to the Patriarch standing stoically, beautifully framed by the archway of his front door. A quick reverse shot further elevates the supernatural standing of the Patriarch eerily similar to Jesus teaching the multitudes on the Mount of the Beatitudes.

We cut between the crowd’s reaction and the gang’s as the Frog slowly straightens out his contorted body at the feet of the Patriarch. We see the smugness of the gang in closeups as the Frog’s fake miracle wins over a shocked and awed crowd. As the audience, we revel in the dramatic irony, looking down on the gullible crowd as they fawn and faint over the sham miracle.

We’re not done yet though. From the same perspective we saw the Frog’s ‘miracle’, we now see the crippled boy slowly limp down the path the Frog just crawled down. He drops one crutch before we cut to his elated face. We cut back out to the medium-long shot of the boy throwing off his crutches and running toward the Patriarch and the Frog. As we cut back to the crowd and gang, our empathies have switched. We find the crowd’s reactions not pathetic but celebratory now sharing their shock and delight. The incredulous and nervous reactions of the gang bring home just how earth-shattering this revelation is, setting up their moral dilemma that plays out for the rest of the film.

Because of the particular sequence of shots and the well-time edits, we feel pride, shock, joy, and intense nervousness alongside the film’s main characters in all in a minute or so. It’s a breathtaking and effective example of the silent screen’s ability to tell a story and convey emotion with nary a word of dialogue in sight (although perhaps the promotional film edited out title cards present in the original version but even a title card or two wouldn’t have diminished the scene’s emotional effect). For such a short snippet, it showcases great acting (especially Chaney’s control over his body), Tucker’s steady directorial hand, and the potential for the rest of the film.

Quite a pictorial reverse shot whose door framing should have made a young John Ford blush.

Upon its release in the fall of 1919, The Miracle Man took the industry and box office by storm. Estimated as the second highest-grossing film of 1919, the film ran for weeks and months in theaters around the country. Critics were effusive in praise for the picture at the time of its release. For example, Motion Picture News‘ review gushed:

There is cleverness, wit, pathos, sentiment and satire which is bound to sway any audience anywhere. This can be truthfully heralded as a big special attraction in an honor class all its own. Decidedly distinctive. Photography and laboratory work exceptionally artistic. Continuity clear as a bell and a stirring love element that appeals.

Even those less effusive in praise for the picture singled out the film’s emotional impact. Variety, writing that “Mr. Tucker starts his story slowly, ends It badly, and lets It drag perceptibly after the big scene”, also stated that “since “Ben Hur” nothing approaching this has been seen on stage or screen, and it has “Ben Hur” beaten seven ways for real sentiment. It is simpler, more true to life as we know it, and so more effective”. Everyone agreed (including me) that the healing scene stood as a great artistic achievement.

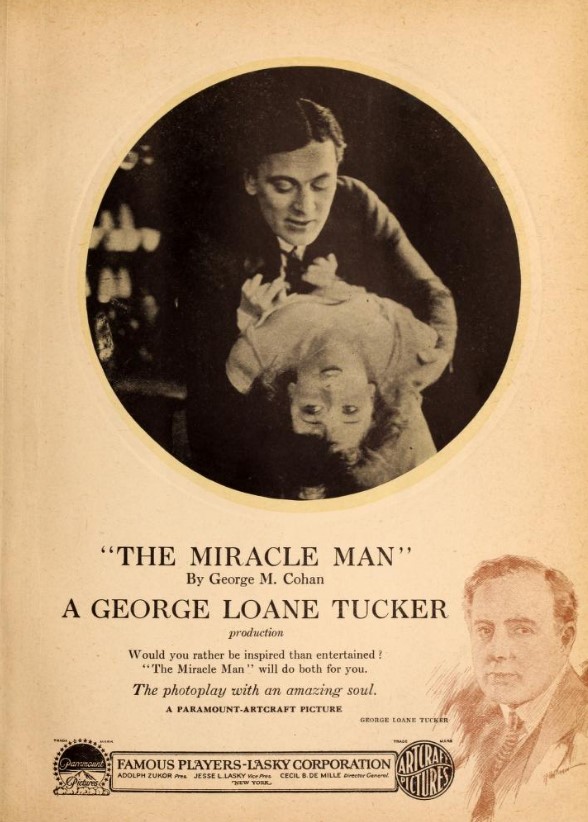

Three ads in Moving Picture World for The Miracle Man. Ads featured George Loane Tucker prominently in lieu of any established stars.

Based on The Miracle Man‘s success with critics and audiences, it became an instant classic. In a letter contest in Photoplay’s July 1920 issue toward the end of its theatrical run, The Miracle Man received more votes than any other film. Throughout the 1920s, it was frequently cited as a high point of cinema, ending up on several best of critics lists and audience polls. It was only a matter of time before such a big, successful property would be remade.

An All-Talking Remake

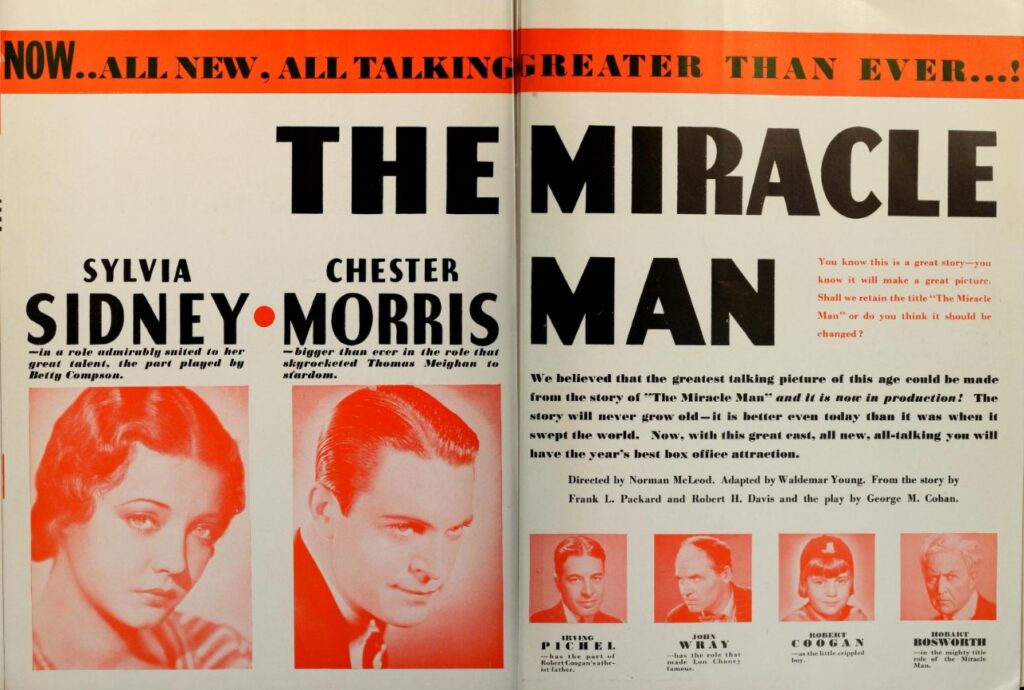

When they remade the film into a sound property in 1932, Paramount was hoping to strike gold again. To play the leads, named Helen and John instead of Rose and Tom this time around, the studio picked two of their top stars at the time in Sylvia Sydney and Chester Morris. They filled the rest of the cast with reliable character actors: the dead-pan Ned Sparks as Harry the Dope, John Fray as the contortionist The Frog, and silent film veteran Hobart Bosworth as the Patriarch. Norman Z. McLeod helmed the direction.

The opening scenes are done extremely well. We open on the streets of Chinatown crossing the paths of a pickpocket and a crippled man, the Frog, begging in the streets. A group of well-off tourists, whose bus almost runs over the Frog, happily throw a few bucks into the crippled man’s hat at the behest of Tom, a generous member of the group.

As the tourists enter a bazaar owned by Nikoo (played in yellowface by the great Boris Karloff) to watch a traditional Chinese parade, a poor woman sneaks in behind them. While the tourists are busy watching the parade on the bazaar’s balcony, John catches the poor woman grabbing money from his pocket. Making a very public scene, the woman breaks down crying, telling her sob story about losing her job and not being able to afford a return ticket to her hometown back in the Midwest. The group, just as they had to the Frog, generously donate their money to the poor woman for her train ticket home.

Instead of leaving for the train station, the woman after the parade enters a well-furnished apartment. She smugly counts her wad of cash before lighting a cigarette, slipping into a sparkling nightgown, and mixing herself a drink on the rocks. Without a word of spoken dialogue, we immediately know the woman Helen is just a common grifter no better than the streetside pickpocket.

Gee, I wish I was that poor!

The pickpocket, the crippled man fully capable of walking around on his own, and John trickle into the apartment, revealing the four as a coherent group of scam artists. It’s an efficient introduction that establishes the very nature of the gang’s characters showing us both their street smarts and utter lack of morals when trying to get what they want. The opening also helps give us a heavy dose of the Great Depression to feel more empathy for the gang trying to make a comfortable life for themselves while scamming tourists with plenty of money.

While the opening follows the novel and 1919 film’s plot to a T, the inspiration for the gang’s grand scheme improves upon past versions. Instead of reading about the faith healer in the newspaper, John stumbles across the faith healer himself. After John throws Nikko down a flight of stairs for creeping on Helen, he gets a train ticket to Meadville a rural and remote town far from the law. When John checks in at the small town’s only hotel and asks where he can get liquor, the clerk suggests he see the town’s miraculous faith healer known as the Patriarch. Ever the skeptic, Doc immediately upon meeting the Patriarch and seeing the whole town’s complete faith in the old man sees a golden opportunity to line his and his gang’s coffers with money.

The remake’s inciting incident works much more smoothly than the original’s and covers up a couple of plot holes. Running away from the law hardens Doc’s character and emphasizes his skepticism. Also, it’s much easier to believe a gang could exploit a small-town faith healer if they stumble upon him themselves. If journalists already got to The Patriarch and he really could heal anyone that came to him in faith, why wouldn’t the whole country already be after him and his powers?

Just as in the original, the whole town wholeheartedly believes in the Patriarch’s power to heal except for one man, Henry Holmes, who keeps his crippled boy Bobbie from seeing the Patriarch. We get an extended scene of the town chiding him for his unbelief in front of the hotel. Walking home, Bobbie asks his father why he doesn’t believe in God. Mr. Holmes dramatically yells at God to strike him down to prove his existence. The scene’s on-the-nose dialogue, clear distaste of the atheist, and Jackie Cooper’s melodramatic performance take you out of the realistic characters the film had so far presented.

The remake’s healing scene is almost a carbon copy of the original, using a nearly identical set and very similar shots as well. The scene works quite well but lacks the same emotional power found in the scene from the 1919 film. A large part of the difference lies in the over-top score used in the talkie remake; however, Leonard was smart to limit his dialogue in the scene and rely on the power of the image. Creating a spiritual scene that isn’t corny is difficult to do but both versions do a decent job of portraying it in a way that doesn’t feel preachy or ingenuine.

Left: Tucker’s framing in the 1919 original healing scene; Right: Leonard’s framing in the 1932 remake healing scene.

After the healing scene, the film loses a lot of steam and goodwill built up through the first half. Histrionics return when Bobbie shows off his healed legs to his unbelieving father. Mr. Holmes weeps with joy, tossing aside his years of skepticism for unwavering faith in an instant. Cooper lays the cheese on thick alongside his father, asking him rather cornily, “How do you pray daddy?”. The shock and awe instilled in the healing scene are completely undone with this unnecessary gaudy scene that is little more than a religious diatribe against unbelief. (In the original the father was a non-believer because of his work as a scientist, a much-needed characterization to make him a more sympathetic figure rather than a mere pawn in a Sunday School lesson.)

The gang similarly turns on a dime. As Helen puts it to Doc, “We can’t go on the way we’ve been. We got to be good.” The next time we see Harry he has already begun dating a local girl, gotten a job as a bank clerk, and quits the gang. The Frog becomes a close friend and devotee of the Patriarch while Helen spurns Doc to spend time with a rich suitor who generously donates to the cause.

Doc is the lone holdout and the vehicle for the rest of the picture’s drama, carrying it as best as he can. While he seems not to question the authenticity of the miracle, he outweighs his scam’s potential payout over a spiritual transformation declaring that “Money will buy me miracles”. Once Harry, the Frog, and Helen officially quit the racket, Doc plans to take the remaining donation money and get out of town. At the last minute, however, he returns after learning that Helen turned down Mr. Thornton’s marriage proposal because she still loves and believes in Tom. With Doc and Helen reconciled and the gang committed to leading good, honest lives, the Patriarch’s work is done. This version ends just as the original did with the Patriarch dying peacefully in his home as the gang stands around him.

The Miracle Man moves on after completing his hardest mission yet: to convert four hardened criminals.

The last of half of the film feels empty and hollow, going through the motions and checking off plot point by plot point as quickly as possible. Supporting characters disappear completely as we strictly focus on the gang, the Patriarch, and Helen’s suitor for the last forty minutes. We never hear back from Nikko and the city, Bobbie and his father, or even the rich paralyzed woman healed by the Patriarch. We simply wait out the last act for Tom to convert, never doubting for a moment he and the gang will go straight in the end.

With such a sudden transformation from ruthless conmen to repented saints, the gang’s transformation is too simple to be believable. The film assumes not only that the Patriarch’s healing is the real deal but that anyone witnessing a miracle will easily accept its veracity and change their life. (The writers must not have ever heard of the children of Israel before.) The gang just automatically become good with little to no effort on their part. They don’t have to give up anything worthwhile to leave behind their world of crime. No need for restitution with those they scammed and no traces of guilt.

Beyond being unbelievable, their transformation lacks gripping dramatic tension. Watching the gang struggle between material wealth and their conscience has the potential to be quite interesting. Could they rationalize away the miracle they saw if it meant securing a life of comfort amidst the Depression? Could they simply enjoy their lifestyle of crime too much to care about their own soul or the welfare of others? We get a small glimpse of this with Doc but not enough to keep us engaged and questioning the outcome of his character arch.

It also doesn’t help sell the gang’s conversion that the Patriarch is a two-dimensional character. Bosworth plays him as a distant mystic, a larger-than-life figure more God-like than human; yet, outside his miraculous healing brought about simply from his faith, nothing about him suggests anything special. All his words are vague Biblical phrases and appeals to others to believe and do good. The on-the-nose organ music that plays in nearly every scene the Patriarch inhabits doesn’t help ground his character much either. He doesn’t require anything from his followers or the townspeople other than believing in God (which apparently is pretty easy to do based on how fast a gang of criminals can become pious doers of good). Besides his miraculous healing powers, there isn’t much to him that would make you instantly change your life to follow him.

Another problem is that once each criminal goes straight, they lose all their unique quirks that made the characters interesting in the first place. After the miracle, the Frog never contorts his body again and Harry gives up his dry humor and quips. It’s really hard to care about these characters when they simply become just another humble townsfolk. We became attached to these characters watching them work their magic in the film’s first act but could care less about them when they settle down and work at the bank or milk cows on the farm.

Just the mere shadow of The Miracle Man can quell any couple’s quarrels!

Contemporary critics were more generous to the film than me, giving the film generally favorable reviews. Motion Picture Herald’s Rita McGoldrick rated the film excellent writing that “a well-known silent picture becomes vocal, with a strong cast giving a dramatically fine performance”. Even though the remake didn’t become a sensation like the original, it did well financially reaching sixth at the May 1932 box office, falling behind classics Grand Hotel and Scarface.

Every review I found online referred to and intelligently referenced the original film when talking about the remake. Knowing how dismissive films studios of their previous silent output as soon as talking pictures took over the industry, a silent film remaining in the theater-going public’s memory for more than a decade is quite an impressive accomplishment.

Twelve years later and audiences still remembered the 1919 version well enough for the studios to advertise the remake based on the 1919 film’s success.

A Miracle of Motion Pictures

Despite the 1932 talkie remake’s close adaptation of the silent classic, it remains largely forgotten today (hence the crappy screenshots I had to use from a 360p version on archive.org) and failed to leave the same mark as 1919’s The Miracle Man.

The original to this day remains amongst the most wanted lost silent films. It remains a pivotal film in the career of Lon Chaney, one of the silent screen’s most gifted actors. (A recreation of the 1919 film’s healing scene appears in the 1957 Lon Chaney biopic The Man of A Thousand Faces. The scene doesn’t quite get the framing right making me wonder if the original film was already lost by then).

Watching the remake today it’s clear to see what audiences would enjoy about the story. The film’s first half sets up the central plot brilliantly, quickly establishing each character while giving us reasons to root for the otherwise unseemly criminals. Even as the ensuing parts of the film fail to capitalize on the great setup, getting bogged down in faith-promoting cliches, the theme of redemption through faith and miracles would no doubt be an appealing story to many religious Americans both in 1919 and 1932.

I wonder if the same problems would plague the original 1919 film if we could secure an extant print to view. The original may have handled the latter half of the film more subtly. Or pantomime, rather than scripted dialogue, was a much better vehicle to capture the spirituality the story aims to seek. In its review of the 1932 remake, Variety theorizes why the remake failed to succeed where the silent film excelled:

Perhaps one element which might have been overlooked in this present-day transmutation of ‘The Miracle Man’ is that basically the ‘Miracle Man’ theme is grand hokum. It’s of a brand of hoke which, somehow, in the passsage of more than a decade since 1919, makes it much more diffcult for cinematic palatability than back in ’19. That wheeze about ‘the world do move’ has seen its answer time and again in pictures which were made from story material of some years back. What was 100% acceptable then too often has required modernization, reburbishing or other treatment to attune it to the immediate present.

It appears, at least in the mind of this reviewer, that 1919’s The Miracle Man by 1932 had already succumbed to changing tastes and morals. Unfortunately, we will never know if the 1919 silent classic would stand up to modern audiences or if it would fail to become a screen classic like its remake. Luckily we have its 1932 interestingly flawed remake and some surviving footage to give us a small glimpse into such a pivotal and well-regarded film from early Hollywood.

Fantastic article! Those little surviving scenes are so tantalizing, especially when compared to the no-so-fantastic sound version. If only some of those lost films could magically be found. I guess there is always hope.

Thanks! I always found it crazy when people get so worked up over and start analyzing frame-by-frame modern movie trailers and teasers but then I realized that I basically do the same thing, just with 100-year-old snippets from lost silent films! A couple of minutes is better than nothing I guess.

Fascinating! It’s too bad this one hasn’t gotten a lot of attention.