Charlie Chaplin’s greatest talent was his ability to mix heartfelt emotion into his comedies. From his touching father-son relationship with Jackie Cooper in The Kid to the utterly honest climactic romantic scene in City Lights, Chaplin manages to give you the warm fuzzies just as easily as he tickles your funny bone. Chaplin best summarized his approach to filmmaking when he described The Kid as a picture with a smile and perhaps a tear.

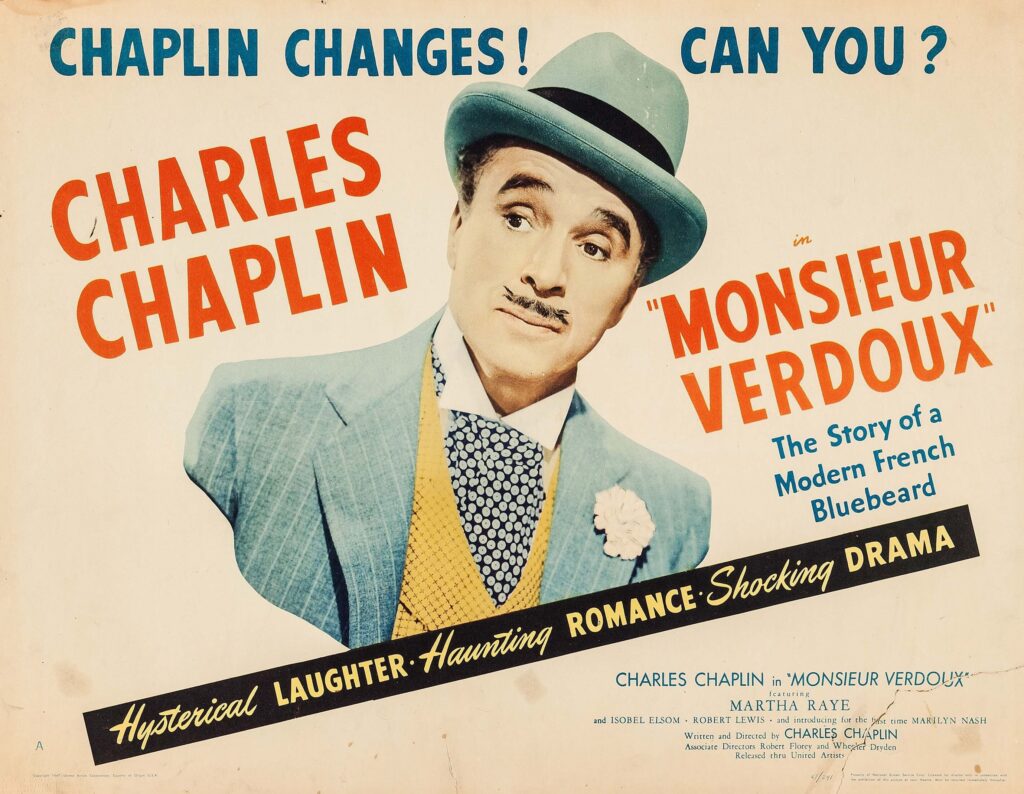

Audiences used to Chaplin’s distinctive mixture of comedy and pathos were thrown off by his 1947 black comedy Monsieur Verdoux. Chaplin plays a middle-aged Bluebeard who marries and kills rich, elderly women to support his wife and young son. At first glance, it is a strange choice for the man behind the tramp. Upon further inspection, however, Monsieur Verdoux is a brilliantly constructed social commentary that uses comedy to manipulate the audience to empathize with a murderer and critique mid-20th century Western society.

Good-bye Tramp, Hello Bluebeard

The film opens on Henri Verdoux’s tombstone as his voice from beyond warmly greets the audience. Not shying away from his crimes, he succinctly summarizes his life and what motivated his character to become a Bluebeard:

For 30 years I was an honest bank clerk, until the Depression of 1930 in which I found myself unemployed. It was then I became occupied in liquidating members of the opposite sex. This I did as strictly business to support home and family. But let me assure you that the career of a bluebeard is by no means profitable. Only a person with undaunted optimism would embark on such a venture. Unfortunately, I did. What follows is history.

His history begins at the home of the bickering Couvais Family somewhere in the North of France. Their sister Thelma has gone missing after marrying a man she only knew for two weeks. After arguing over the issue, the family decides to take the man’s picture to the police if Thelma doesn’t appear in the next couple of days.

Funny looking bird, isn’t he?

Unfortunately for the Couvais family, Thelma won’t be showing up anytime soon. As they speak, her remains burn in an incinerator at Monsieur Verdoux’s picturesque villa in the south of France. Verdoux has successfully withdrawn sixty thousand dollars from Thelma’s bank account. Now he is in midst of selling off the villa and hurriedly disposing of any evidence of his and Thelma’s all-too-brief honeymoon. When a wealthy widow named Madam Grosnay appears to view the villa, Verdoux wastes no time professing his love to her in hopes of acquiring yet another investment to current assets.

From just this opening, we get a complete picture of Verdoux’s business modus operandum. Always on the clock, Verdoux constantly searches for wealthy widows to add to his growing list of murders. He assumes various aliases from a sea captain rarely onshore to an engineer working on a massive building project in Southeast Asia. After a shotgun wedding, Verdoux leaves his newlywed to tend to his other business affairs. He returns when strapped for cash, persuades his impatient wife to withdraw her money from the bank, murders her, and disposes of the body.

His business ventures support his paralyzed wife and young son who he dashes home to see between his various sham marriages and murders. While he rarely gets the chance to spend more than a day with his wife and son, his Bluebeard lifestyle pays for a lovely home complete with a beautiful garden and maids. A much better living arrangement than they had when he worked as a bank teller for three decades indeed.

A family a man would kill for

For the majority of the film, we follow Verdoux as he hurriedly travels around France juggling his wives and dodging the law. We see him experiment with a new drug meant to kill his wives painlessly within an hour, aggressively woo Madam Grosnay, and struggle to successfully kill his pesky wife Annabelle, a dim-witted socialite who happened her fortune upon winning the lottery. All the while Verdoux keeps his upbeat demeanor, carrying out his business for the sake of his family and perhaps for his own entertainment as well.

*SPOILER WARNING* Monsieur Verdoux’s fortunes change when Europe falls into economic collapse and war. He promptly loses his fortune to the panic and shortly afterward loses his wife and son to premature death. Years after giving up his Bluebeard lifestyle and wandering aimlessly through life, he turns himself into the police when the Couvais family spots him in a restaurant.

He uses his trial and publicity to condemn those profiting and encouraging the mass killing ramping up in Europe in the 1930s. Admitting his guilt, he laments that he must pay for his crimes as a murderous businessman while war profiteers face only acclaim and massive wealth. The final shot of the film calls back to the many iconic endings of Chapin’s silent works. Monsieur Verdoux walks offscreen into the distance—not to his next adventure as the Tramp does in films like Modern Times but to the guillotine. *SPOILERS OVER*

Turns out that crime DOES pay!

Merely describing the film’s plot doesn’t do justice to the humor baked into nearly every scene. There is nothing humorous or likable about a man murdering numerous vulnerable elderly women solely for their money; yet, Chaplin injects this dark premise with uproarious comedy.

Take Chaplin’s physicality when charming the wealthy widow Madam Grosnay. Up to that point in the film, Verdoux had been a pretty genial but straight-laced man moving through the motions of his business. Upon meeting Madam Grosnay and hearing that she had never remarried after his husband’s death, Verdoux immediately changes his demeanor to an impish suitor incapable of controlling his hormones. Literally throwing himself at Madam Grosnay in an attempt to show his uncontrollable desire, his over-the-top, desperate attempts at romance generate laughs from the audience. Seeing him humiliate himself in such an embarrassing fashion, we easily forget the dire consequences facing Madam Grosnay if she falls for Verdoux’s theatrics.

Just a simple boy in love

Chaplin’s own performance as Monsieur Verdoux allows the film to walk a delicate tightrope between comedy and sinister drama. One minute Chaplin is fluttering about spouting cheesy poetry and falling out of windows in attempts to seduce a widow. Next, he is coldly proposing testing a deadly poison on a random vagrant on the street in the same tone one would discuss investing in the stock market. Verdoux’s sinister apathy for the lives of his victims is only digestible for the audience because of his genteel nature and the bits of comedy that lighten the mood and lift the audience’s spirits.

Chaplin’s physical moments of comedy are equally matched by his most pesky wife Annabelle played wonderfully by Martha Raye. While the other women in the film are meant to merely be unsympathetic and devoid of personality, Annabelle is a burst of energy. Her cantankerous attitude, nonstop chatter, and defiant individuality provide the perfect foil to Verdoux’s coldly composed killer experienced in manipulating his wives into handing over their fortunes to him. In the film’s funniest scene, Annabelle avoids Verdoux’s attempts to drown her, chloroform her, and strangle her without ever knowing her strangely acting husband is standing behind her in the middle of a remote lake with several weapons of murder.

A Place in the Sun with a slightly happier ending.

Beyond merely providing the audience laughs, the film’s comedy allows the audience to more easily identify with the morally bankrupt Monsieur Verdoux. Painting the majority of the film’s characters as unsympathetic or flat-out annoying helps further shift audience sympathy to Verdoux. The Couvais family is an overbearing, fickle family you wouldn’t want to have dinner with. Verdoux’s dowdy, uptight wife Lydia entirely lacks any appealing characteristics so much so that we hardly feel anything when Verdoux murders her offscreen. The less we identify with and care about these characters, the more forgiving we are to Verdoux’s murderous behavior.

While the film is purposefully constructed to allege our sympathies with Verdoux, it never fails to sugarcoat his actions or even excuse away his behavior. Verdoux right from the opening narration is upfront about his guilt. It is a delicate balance that draws us into the story without asking us to fully put aside our own judgment against Verdoux’s senseless murders.

Putting the Dark in Dark Comedy

The most important function of Monsieur Verdoux‘s comedy is to act as an essential counterweight to the dark message of the film. A two-hour anti-capitalist creed would be a rather tiring ordeal; however, two hours of comedy with a moralistic ending is much more digestible.

After focusing solely on Verdoux’s life of crime for the majority of the runtime, the final scenes of Verdoux on trial and in jail widen the scope of the film to explicitly discuss international affairs of the world. Verdoux turns the condemnation of his own murders to those of the world’s largest nations and armies:

As for being a mass killer, does not the world encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? Has it not blown unsuspecting women and little children to pieces? And done it very scientifically? As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison.

Verdoux’s speech is not a defense of his own murders but a blasting critique of post-World War II Western nations on the brink of the Cold War. If Verdoux’s handful of economically minded murders are punished with death, why should a munitions dealer receive wealth, acclaim, and the gratitude of society for creating the methods of mass execution? The almighty dollar has no regard for morals or any disdain for death and destruction. Verdoux’s life is a stark warning for any society that worships wealth and money to the point that one’s own personal well-being and success devalues other humans to disposable numbers and figures.

For a guy known mostly for his silent work, Chaplin’s a pretty good orator.

While Monsieur Verdoux‘s closing political message is rather black and white, and for some a little too on the nose, Monsieur Verdoux also works as a fascinatingly complex character study into the life of a narcissistic mass murderer.

Monsieur Verdoux throughout the film projects a character that masks his own feelings and morals from those he interacts with. With his family, he is the noble, loving provider. Around his wives, he is the ultimate businessman methodically adding to his bottom line. When wooing wealthy widows, he is a great lover (or tries to be). Even when on trial and surrounded by journalists and reporters, Verdoux is a moral outsider warning the public of the corrupt system they are complicit in.

We finally see a genuine Verdoux stripped of any disguise when he takes in a young woman (played by Marilyn Nash) alone off the dark streets one night to test his experimental poison. Just having been released from a three-month jail sentence that day, the woman is the perfect victim that wouldn’t attract any unnecessary attention to Verdoux’s business ventures.

A rare glimpse of Verdoux’s humanity

While he prepares a small meal and mixes the poison in with her wine, Verdoux and the woman enter a deep discussion about the dreariness of existence. With a knowingly sinister smile, Verdoux asks the woman if she would welcome death if it were quick and ultimate, “Wouldn’t you prefer it to this drab existence?”. The woman responds with a stern no. She chooses to keep living despite her current situation because love gives her life meaning. The woman tells Verdoux that she had once loved her husband, an invalid veteran who depended on her for his everyday survival. Being wanted and loved made her feel life was worth living. Declaring she would have killed for her love, Verdoux decides to spare her life since she, like him, has something to live for.

It’s a striking decision for the character. Verdoux has completely reduced others to pawns in his business dealings. His many victims are merely a means to achieve financial stability for himself and his family. Business, business, business. For a brief moment, he sees the woman as a person and as an equal. This brief moment gives us a glimpse past Verdoux’s veneer as a businessman showing us he isn’t too far detached from humanity to feel anything beyond his bottom line.

In fact, his murders are committed out of love. Verdoux loves his wife and child so much that he literally kills for them. Furthermore, he seeks to justify his cold-blooded murders as mercifully ending the pain and suffering of women too lonely to find love in the world.

Remember Verdoux’s assertion that it takes an optimist to become a Bluebeard? Verdoux’s version of optimism is not that life is worth living but that death is a release from the suffering and pain of life, not the dreaded outcome most people fear. His inner psychology provides both the reason and justification for his homicidal behavior. His behavior came not from a place of hate but a place of venerability, determined after losing his job to ensure that the one thing he cared about was taken care of no matter the costs.

Roles reversed

When he meets up with the woman years later on the street, their roles have reversed. Now married to a wealthy munition manufacturer, the woman lives comfortably and gives Verdoux a free meal. She is now the one questioning Verdoux’s philosophy of life while Verdoux ruminates on the particulars of his own misfortunes.

When Verdoux declares he now has nothing worth fighting for after losing his family, the woman tries to convince him that life is still worth living. Unlike their first meeting, the woman fails to convince Verdoux of the beauty of life. While the woman’s hope had once caused him to spare her life, seeing the woman in a marriage built wealth and prosperity over love convinces Verdoux to give up on life and turn himself into the police. Verdoux now sees himself just as the many widows he murdered, without love and any hope to find meaning in life. He has lived long enough to fulfill his destiny and now hopes to at least rail against the cruel society that turned him into a cynic before he leaves it.

His brief interactions with the woman show us that Verdoux’s all-business demeanor was a mask that shielded him from the insecurity and the humiliation of losing his position in society. In his own words, his life as a Bluebeard was “a numb confusion, a nightmare in which I lived in a half dream world, a horrible world”. Having lost everything in the ruthless business world, Verdoux vowed to do whatever it took for him to never be tossed aside again.

These brief glimpses beyond Verdoux’s outward cynicism allow us to see him as a tragic, sympathetic character. We pity not that Verdoux pays his life for his crimes but that his obsessive drive to ensure financial success prevented him from enjoying the love and companionship of his family.

After getting this dark I’m pretty exhausted too.

A Message with Perhaps a Laugh

In the film’s final scene, a journalist comes to Verdoux’s cell on his execution date with a favor to ask of him.

“Listen, Verdoux, I’ve been your friend all through the trial. Now, give me a story with a moral to it! You, the tragic example of a life of crime.”

Chaplin easily could have formulated his picture into such a morality tale that painted Verdoux as a stark warning to those in the audience audacious enough to commit murder. All too many Hollywood films of the time shoehorned a nice, easily digested morality tale in its last five minutes, completely negating the darkness or subversion of the previous 80 minutes of the film.

What makes Monsieur Verdoux such a great dark comedy is Chaplin’s refusal to give the audience easy answers. We aren’t supposed to merely come away from the film with a renewed distaste of murder. Instead, we are to ask why we are more willing to accept ruthless business practices amongst countries and corporations than when an individual commits these same crimes.

Because of its ambitious scope and complex characters, Monsieur Verdoux is one of Chaplin’s most fascinating and unique films. It’s quite an artistic achievement to pack that many laughs into such a potent and timely message that doesn’t shove its point down your throat. A remarkable picture with a message and perhaps a laugh.

This review was nominated for Best Film Review (Musical or Comedy) 2023 by The Classic Movie Blog Association.

This post is part of MOVIES ARE MURDER! a blogathon hosted by the Classic Movie Blog Association. Visit the blogathon’s main page to read about more than a dozen of murderously delightful films.

I greatly enjoyed this superb post, Shawn! I’ve only seen a few Chaplin films, and none of his non-silents. I do consider myself a fan, though, and I’m definitely a fan (usually) of dark comedy. And I’m fascinated by the idea of the film’s deeper messages. You have totally convinced me to check this one out. Thank you for contributing your first-rate write-up to the blogathon!

What an absolutely perfect choice for the blogathon. Chaplin had a lot to say about serious issues and wove them into a complex and comic coat. And of course, he simply could not resist that hilarious boat scene with the great Martha Raye. Thanks for a lovely and thought provoking post.

I avoided this film for years because I felt I wouldn’t like it, but I really fell under its spell when I finally did see it.

Casting Martha Raye was a stroke of genius.

Well written! I’ve considered watching this many times but haven’t gotten around to it. Will definitely make it more of a priority.