It’s not very often that a filmmaker gets to remake his or her own movie. Directors are lucky enough to make two separate movies let only the same movie twice! There are however a few examples of a director looking back to their earlier days to revamp and redo a past project: Abel Gance with J’Accuse (1918 and 1938), Alfred Hitchcock with The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934 and 1955), Yasujiro Ozu’s with A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) and Floating Weeds (1959), and Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956) just to name a few.

Perhaps no filmmaker found more critical and box-office success when remaking his own movie than Cecil B. DeMille. He remade his 1923 immensely popular biblical epic The Ten Commandments in 1956 with the likes of Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, and Edward G. Robinson, collecting critical acclaim and one of the largest box-office hauls in Hollywood history. While many are familiar with this 1956 remake, largely thanks to ABC’s long-time tradition of showing the film on Easter weekend, the 1923 original is often only a footnote when discussing its remake. Let’s try to fix that by giving the film a second look.

Lead up to The Ten Commandments

Long before the film’s release, the film was a HUGE DEAL! Cecil B. DeMille at the time was one of Hollywood’s biggest and most established directors. As a director working for Paramount Studios, he had made a star out of Gloria Swanson with his popular risqué comedies such as Male and Female (1919) and Why Change Your Wife (1920). DeMille was also known for his extravagance and penchant for showing his audiences the everyday lives of the rich and glamorous. Naturally, a big-budget project by DeMille, based on a story from the most well-known book in the Western world, would be a topic of interest for much of the industry and the public.

The idea itself was part of a publicity stunt that only could have happened in the Golden Age of Motion Picture magazines. In an article in the Los Angeles Times in October 1922, DeMille announced a contest calling for ideas for his next picture. Eight contestants won the contest by suggesting a film based on The Ten Commandments, with F.C. Nelson succinctly writing “You cannot break the Ten Commandments—they will break you.”

DeMille’s No Strings Attached Contest printed in the October 9, 1922 issue of the Los Angeles Times.

With a theme in hand, DeMille needed a story behind it. Luckily for him, as the Los Angeles Times article states, “he has in Jeanie Macpherson a famous artisan in the construction of finished photoplays”. After toying around with several ideas including an episodic structure that would address each of the Ten Commandments separately, Macpherson and DeMille settled on telling the story of Moses in a long prologue to the film followed by a modern-day morality tale focusing on obedience to the Ten Commandments.

For anybody who has seen the 1956 version, this structure comes as a surprise. You might be thinking on your first viewing that the story is moving extraordinarily fast. Moses starts out old and the film skipped over nine of the ten plagues! A little bit over forty-five minutes in, the ancient Biblical retelling of the Exodus story ends and gives way to a modern 1920s story featuring regular people who never get the two-strip Technicolor treatment. This harsh transition would be no surprise to audiences of the day unless of course the motion picture fan magazines of the day didn’t get delivered to the front porch of the rock they lived under.

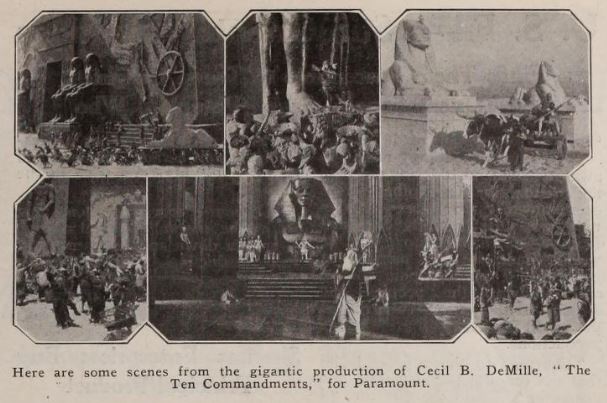

Motion Picture World released these publicity stills of the set months prior to the film’s premiere.

Magazines marveled at the gigantic sets DeMille built for the production of the Biblical prologue. Motion Picture News reported in July that DeMille finished his Biblical prologue and now working on adding cast members to his the film’s modern story. The press and fan news built up to the film’s premiere on December 4, 1923, in Los Angeles to numerous rave reviews, mainly commending DeMille on his epic and grand retelling of the Exodus story.

The film lived up to its pre-production hype with the public as well, becoming one of the biggest blockbuster hits of the silent era. Now in 2020, the film is easily accessible in the public domain and ripe for a second look. Of course, a few things have changed. America and much of the world are much less religious or willing to shell out money for a didactic tale about obedience to the God of Israel; nevertheless, The Ten Commandments still stands as one of the most ambitious entries in all of Hollywood silent film. Not to mention, it is a good film to introduce people to Cecil B. DeMille’s numerous entertaining and well-made silent features. A good public domain version of the film, with the two-strip technicolor scenes, is available free online.

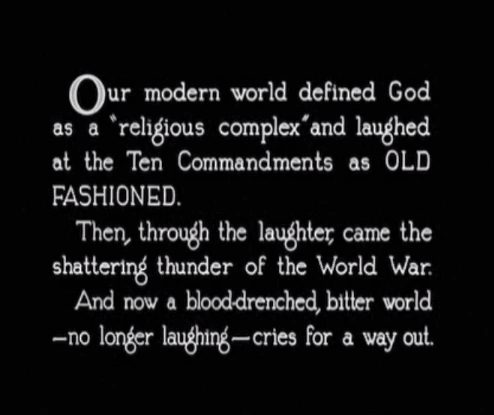

Thou Shalt Not!

The film shows its overarching theme and goal right off the bat just in case the title didn’t clue its viewers into it: follow the Ten Commandments or else! It opens on the children of Israel slaving away as an Egyptian taskmaster, played by the wonderful character actor Clarence Burton who shows up in a lot of the DeMille brothers’ films, whips and berates them. This scene does a good job of showing us the plight of the Israelites while also allowing the viewers to enjoy the huge set that includes not only several large Phinxes but God himself! Well, the living Epytian god some people call Pharoah in all his pomp and glory at least.

Well, roll credits!

After a poor Israelite has been crushed to powder to drive home the point that things can’t get much worse for the Israelites, we cut to Pharoah’s luxurious court. Moses and Aaron come from afar to convince the Pharoah to let their people go. We learn the first nine plagues have already occurred and that this hasn’t softened Pharaoh’s heart at all. Also, we find out the Pharoah’s son is a bit of a brat with terrible manners! (I don’t know if the filmmakers were trying to go for a “kick the dog” trope by replacing it with “whipping the prophet”.) Regardless, Moses leaves the court of the Pharaoh with an ultimatum: let my people go or God will kill the firstborn of every Egyptian.

I mean, Moses did technically threaten to kill the kid two seconds earlier so he can’t be ALL that bad!

Pharaoh finds out that Moses and God sure meant business when all the firstborn sons in Egypt die, including his own son. His heart finally softened, Pharoah lets the Israelites take up all their belongings and leave en masse. The crowd scenes of the Israelites leaving Egypt are stunning, particularly for modern audiences used to CGI armies and hordes. DeMille is able to masterfully interweave the grand and the mundane, cutting between long shots with thousands of extras moving about in organized chaos and medium shots detailing the intimate actions of a few individuals.

A family struggling to hear their small flock of sheep, a woman praying in thanksgiving as she loads her donkey, and a young girl holding onto her doll lost in the hustle and bustle of the crowd. We are caught up in the excitement, hope, and joy of Israel’s emancipation from Egyptian slavery without losing sight of the pain and fear that each Israelite feels as they leave their homes and look forward to an uncertain future.

Are we there yet?

Unfortunately for the Israelites, Pharaoh’s heart hasn’t softened all that much (he did let his son whip a prophet once you know!). Pharaoh chases after the Israelites and has them cornered up against the Red Sea. Little does he know, besides witnessing TEN PLAGUES firsthand, Moses wields the power of God and parts the Red Sea, allowing the Israelites to pass through unharmed on dry ground.

This is by far the most famous scene in the film. Beautiful two-strip Technicolor combined with cutting-edge specific effects brings God’s miracles of fire falling from heaven and the parting of the Red Sea to the screen. In the end, all of Pharoah’s chariots and all the Pharoah’s men couldn’t bring Israel back to Egypt again, drowning in the depths of the Red Sea.

Fun fact: The Red Sea is actually water pouring over jello played in reverse with the children of Israel put into the frame through a well-executed double exposure shot.

The film jumps to the children of Israel in the Sinai wilderness three months later. Moses is up in Mount Sinai getting the Ten Commandments from the Lord. Meanwhile, the restless Israelites thought it might be a good idea to build a golden calf to worship and have an orgy or two. (The scene is pretty calm for a DeMilliean orgy, nowhere near the level of the one in Sign of the Cross).

God does not think that is a good idea (as the Israelites will find out when they read commandment #3) and sends Moses back down to set things straight. Moses hands out leprosy like Oprah, smashes the stone tablets in anger, and calls up for God to destroy the wicked Israelites with lighting, wind, and falling rocks. Sadly if you want to know what happened next to the children of Israel, you’ll have to pause the movie and pick up a Bible and read all the way from Exodus to Joshua. The film fades from death and destruction to a family sitting around the kitchen table reading from the good book itself.

So, I heard you liked Golden Calves?

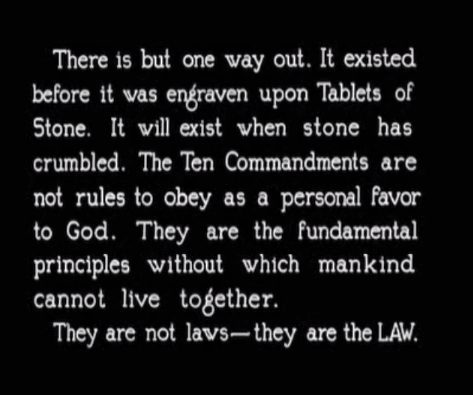

Before we get into the modern story, this is a good place to take stock of the prologue and prepare us for what is to come. The story itself takes little liberties from the original Biblical account found in Exodus, going so far as quoting scripture in many of the title cards. The artisanship and beauty don’t come in the things added to the plot but in the way in which DeMille and his crew depict these well-known events.

Characters have no explicit motivations or backstories. The history of the Israelites or an explanation of their religion and beliefs don’t take center stage. Instead, our knowledge of the story of Moses and the children of Israel brings simplicity to the film that doesn’t force upon us an interpretation of the events onscreen. We see the events unfold as is. The Godly is treated as fact and we as the audience accept it through innovative special effects. It never comes across as preachy, instead playing out as a lesson in Israelite history with a side of morals.

Almost a hundred years later and the special effects are still lit.

The Biblical prologue is the better-known part of the film and remembered for its grand sets and innovative special effects. Critics and audiences of the day universally lauded DeMille’s retelling of the Exodus while the modern story divided critics and audiences alike. Let’s find out if a modern story meant to teach us a Sunday School lesson can succeed while competing with the breathtaking Biblical prologue succeed.

Modern-day Moses

As previously mentioned, one fade takes us from the second millennium in the Sinai wilderness to 1920-something in what looks like a Midwestern American family home. An aging mother finishes reading from the book of Exodus to her two adult sons sitting at the kitchen table. We quickly learn that Dan (Rod La Rcoque) would rather worship a five-dollar coin than the God of the Ten Commandments. John (Richard Dix) on the other hand is a devoted and loving believer in God, the Bible, and the commandments.

Guess who is having the most fun at this family get-together?

An impoverished girl named Mary (Leatrice Joy) enters the picture, creating a love triangle between her, Dan and John. Before John can profess his love for Mary, Dan wins her over and proposes. The newly engaged couple get kicked out of the house by Mrs. McTavish (Edyth Chapman) when they do the unthinkable: dance on the Sabbath! As Dan leaves the house with Mary in tow, he declares that he and Mary will “break all ten of your old Commandments, and we’ll finish rich and powerful!”. We’ll see what God (and the screenwriters) say about that!

Remember commandment number seven, John. Remember commandment number seven!

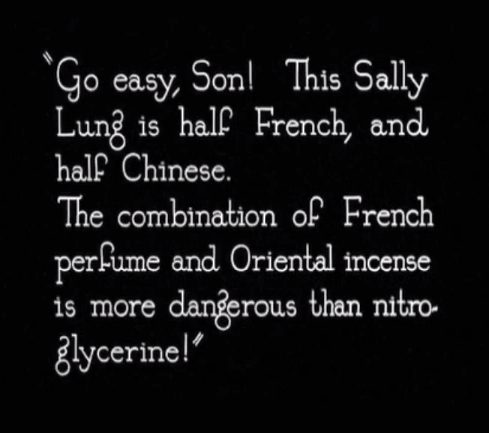

Three years pass and Dan has kept his promise. He has become the state’s most successful building contractor while John is still just a humble carpenter (does that remind you of anyone in particular?). Dan is building a fine career of breaking the Ten Commandments with his latest and greatest sin, lying about the quality of cement used in building a church to save himself a few bucks. Let’s not forget to mention his new half-French, half-Chinese mistress Sally (Nita Naldi) who herself happens to be fresh off a leprosy-contaminated ship from Molokai, unbeknownst to Dan.

After a good run of three years, breaking the Ten Commandments finally backfires on Dan when his building built with weak cement falls on and kills his mother when she comes to visit the church construction site. Mrs. McTavish in her dying words blames herself for Dan’s bad life decisions, bewailing her regret of having taught him “to fear God, instead of to love Him”.

Oh, look. A cold-blooded, heart-wrenching murder! Just one more for disobedient Ten Commandment Bingo. I am loving this!

Dan fails to turn things around following the death of his mother, digging further and further in sin to cover up his immoral business and life decisions. To make matters worse, the law is now after him once he murders his mistress Sally when he contracts leprosy. Dan meets his end running away to Mexico in a speedboat named Defiance, crashing into a rock formation that looks awfully close to two stone tablets. Hmm… I wonder what that could possibly mean?

The film closes as Mary runs to seek help from John who accepts her with open arms, a quality apparently shared by many carpenters. While Mary is afraid she contracted leprosy from Dan, John assures her that Christ can heal anyone, sharing the story of Christ healing the leper from the New Testament (with a brief cameo of DeMille’s previous leading lady Agnes Ayres). The film fades out as John and Mary embrace, both committed to keeping the Ten Commandments and free of leprosy.

In Biblical epics, the Ten Commandments break you!

Sacred or Saccharine?

It’s not very surprising that there are a lot of allusions to the Bible throughout the film and a LOT of motifs. The two stone tablets get enough screentime to warrant a credit in the film, playing witness to the deaths of both Mrs. McTavish and Dan. Leprosy is used as a punishment for wickedness in both the prologue and the modern story. Dan meets a fate similar to Pharoah’s chariot riders, wearing much less fashionable clothing sadly.

The film hits its message a little bit too much on the nose. For instance, the motorboat that Dan takes to run away to Mexico is named Defiance. We even get a close-up just in case you didn’t notice!

Wait, is he defying God or something?

The characters are problematic and simplistic as well. Of chief concern is Sally who is portrayed as the embodiment of sin and lust. Her character is unfortunately exoticized when her heritage is used to show us her dangerous sexuality. It doesn’t help that her seedy place of residence is highly stereotypical of Asian identity of the time period.

The other characters are not much more fleshed out. Dan seems to be only interested in disobedience and immorality while John can do nothing wrong.

Well, that’s racist!

To give it the benefit of the doubt, the film purposefully aimed to paint almost allegorical characters that stood for various types of people. As quoted in Robert S. Birchard’s book Cecil B. DeMille’s Hollywood, Jeanie Macpherson, the talented The Ten Commandments screenwriter, wrote this about the modern story in her treatment for the film:

There are four people in the modern story of The Ten Commandments, and they view these Commandments in four different ways. There is Mrs. McTavish, the mother, who keeps the Commandments the wrong way. She is narrow. She is bigoted. She is bound with ritual. She is a representative of orthodoxy, yet withal she is a fine, clean, strong woman just like dozens we all know.

There is a girl, Mary Leigh, who doesn’t bother about the Ten Commandments at all. She is a good kid, but she has spent so much time working that she hasn’t learned the Ten Commandments.

Dan McTavish knows the Ten Commandments, but defies them.

John McTavish is a garden variety of human being, which believes the Ten Commandments as unchanging, immutable laws of the universe. He is not a sissy or a goody-goody, he is a regular fellow, an ideal type of man of high and steadfast principles, who believes the Commandments are as practicable in 1923 as they were in the time of Moses.

Each character is a representative of one value: Mrs. TcTavish is orthodoxy, Mary is ignorance, Dan is defiance, and John is obedience. While this construction adequately communicates the filmmakers’ belief that obedience to the Ten Commandments remains relevant in the modern-day, this construction fails to get us much invested in the story.

The characters are more abstractions than the people we know in our lives. The choices of the characters are dictated by the morals the filmmakers are trying to teach the audience, not their inner motivations and desires. Dan stands as an example of what happens to non-believers, never reaching a three-dimensional character. The modern story plays out like a Sunday School lesson which depending on your own personal and religious beliefs may be a great or bad experience for you.

I wonder if DeMille used this shot of Christ healing the leper in the trailer for his The King of Kings (1927)?

One part of the modern story that I find interesting and fresh is Mrs. McTavish’s role in Dan’s disobedience. While not accountable for Dan’s actions, Mrs. McTavish realizes that her failure to focus on the love taught in Christianity had a negative impact on her son. The film suggests that there is in fact a wrong way to do good. Mrs. McTavish is just as stubborn as Dan albeit for a much better cause.

Holding onto any standards or rules in any lifestyle, whether religious or otherwise, in disregard of the feelings and thoughts of others is not attainable and leads to destruction. Love, which seems to have been absent in the Biblical prologue, is added as a necessary ingredient to any religious observance or moral guideline. Highlighted by the scene of Christ healing a leper near the end of the film, the forgiving and loving God of the New Testament takes precedence over the God of the Old Testament who destroyed Egyptians and Israelites alike.

Overall, the Biblical prologue sets a high standard of filmmaking that the modern story of the film cannot fully live up to. While by no means a slog, the modern story attempts to match the stoicism of the Biblical prologue but only manages to create many stereotypical and one-dimensional characters in its overly didactic form. Cecil must have agreed with this assessment of the modern story: he cut it out when he remade the film.

As a believing Christian I found this silent version to be a teachable reminder of the depth of the meaning of personal growth in faith. Our reward is at hand!