Homer Croy’s 1918 book How Motion Pictures Are Made has the best case for the earliest attempt at providing a comprehensive history and survey of the film industry to a general audience. Written several years before Hollywood studios solidified a working business model and hierarchal assembly line for mass-producing movies, How Motion Pictures Are Made stands as an invaluable time capsule into the earliest days of film production.

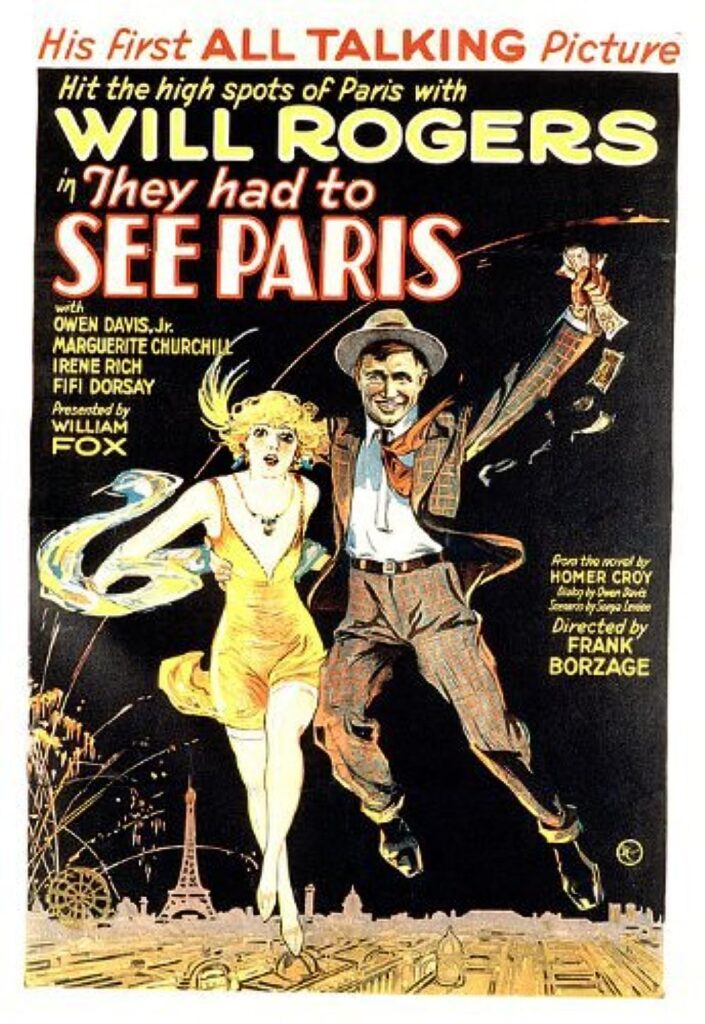

Croy leans on his unique experience directing travelogue shorts in the mid-1910s and exhibiting films to soldiers in World War I France to relay to the layperson the workings in front of and behind the camera. He’d go on to write the biographies of Will Rogers and D.W. Griffith along with several novels that later became their own Hollywood adaptations including Rogers’ first sound film.

(Left) Author Homer Croy and his biggest claim to fame: writing the novel that became the story for Will Rogers’ first talking picture (Right)

The first three chapters detail the development of motion picture technology from Muybridge’s early experimentation with glass plates to the moving picture’s establishment as a lasting entertainment by the turn of the century. This expectedly outdated history is most notable for what is not included. For instance, Croy mentions the Lumiere brothers only briefly mentioned twice instead focusing almost exclusively on the American businessmen and inventors who worked on early cameras and projection equipment.

The real fun begins as Croy dives into his contemporary Hollywood. Following the production of a film from the initial creation of the story manuscript up until its exhibition, the book outlines the basic methods of 1910s filmmakers. It’s striking how most of the basic processes remain essentially the same over a century later. From breaking down the story into different scenes to casting the film’s principal players, modern readers will recognize the workflow albeit with a few slight modifications due to the available technology of the time.

The simple language drives home just how little audiences understood cameras and the filmmaking process in the years before affordable cameras appeared on the market for home consumers. For example, a brief explanation clarifies the meaning of a retake not expecting readers to understand the meaning of this now ubiquitous concept. Even though some of the production methods described seem common knowledge for any Film 101 student today, Croy’s clearly explained examination of Hollywood productions fills in the gaps first built upon what audiences had seen depicted onscreen and read in motion picture fan magazines.

After detailing the production of a motion picture from beginning to end, Croy devotes two chapters to sharing the secrets behind creating special effects in early trick films and later dramatic works. This section stood out from the book, proving a rare look inside the particular practices and in-camera tricks utilized by cameramen to capture double exposure. I’ve never read a more clear and concise explanation of how silent filmmakers created double exposures, stop-motion effects, and in-camera fades.

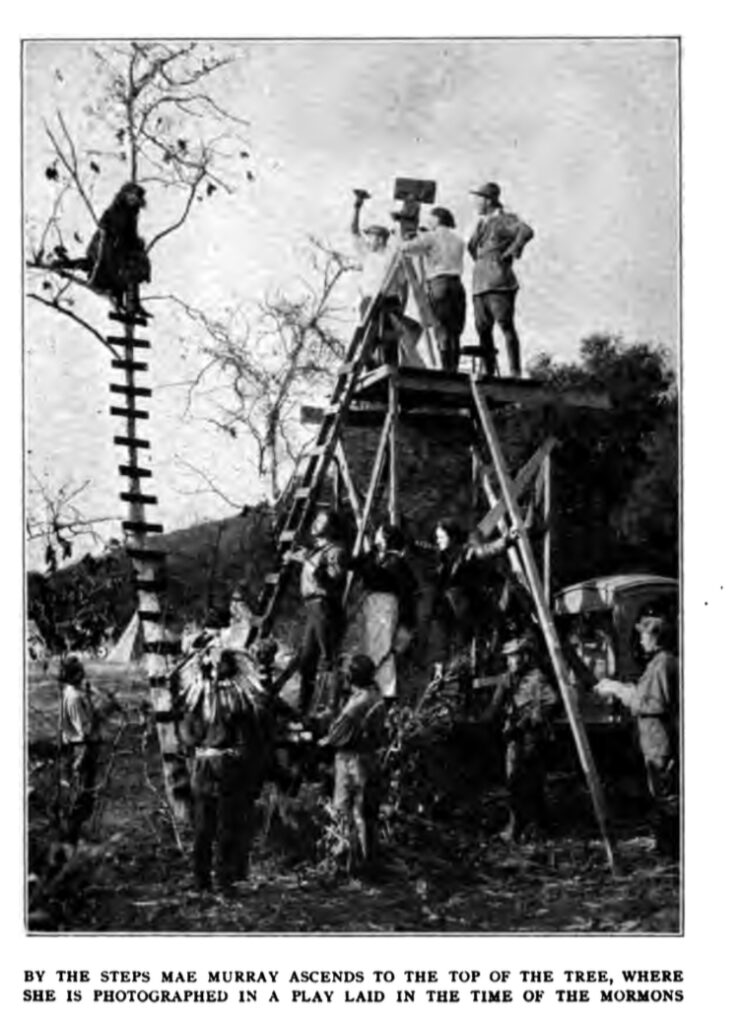

In a couple of instances, Croy pairs his clear explanations with stills and behind-the-scenes shots of cameramen at work. To create the illusion of knives hurling towards their leading lady, a propman pulls knives out of the wall with invisible strings as the cameraman cranks the camera in reverse. A simple but effective practical effect that still captivates audiences today.

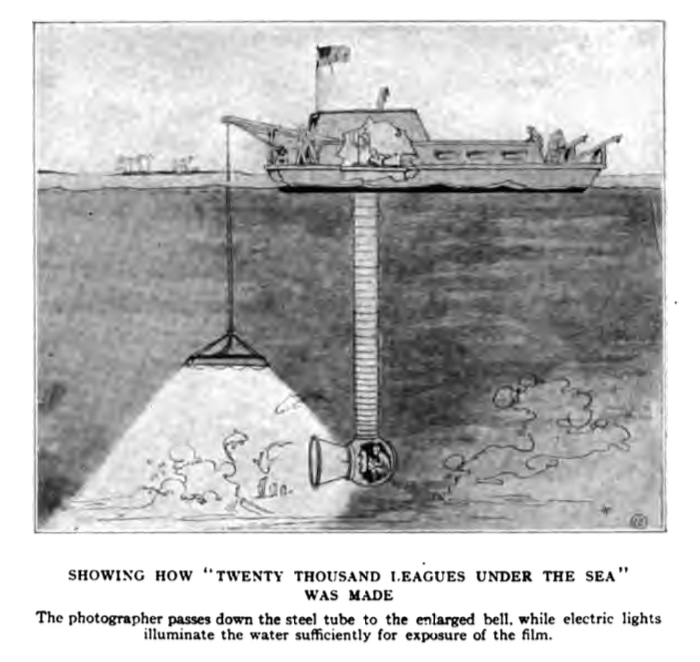

Croy devouts the remainder of the book covering a smattering of topics covering various aspects of motion picture including animation, film advertising, and the secrets of slapstick comedy. The chapters on both color and talking pictures cover a forgotten history of early experimentations with technology that had not yet become commercially sustainable let alone dominant. A chapter on underwater photography contains a deep dive (pun intended) into the filmmaking processes pioneered during the 1916 adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea with some breathtaking photos taken under the ocean only a few years after such technology made this possible.

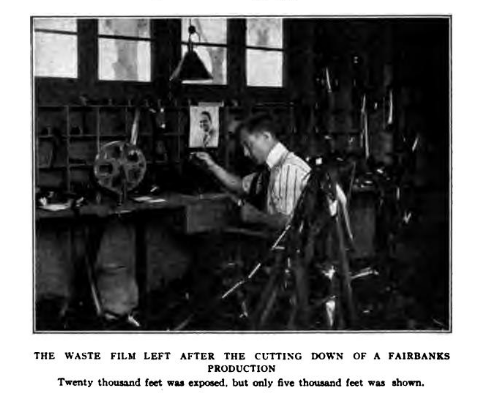

The book is littered with great, but low-quality, behind-the-scenes photographs. We see plenty of candid shots of recognizable stars like Douglas Fairbanks, Alla Nazinova, and Charlie Chaplin alongside numerous unnamed behind-the-scenes talent. I imagine people in 1918 would frequently see popular stars in magazines but rarely any glimpses of those working behind the scenes.

My favorite photographs capture the technicians working hard to create the perfect shot. One features an assistant holding up a screen to reflect sunlight softly onto a couple embracing in a lake. Also, I’ll always get a kick out of spools of nitrate film spread haphazardly across a disheveled-hair editor’s film bench.

As to be expected from a book over a century old, much of the information is out of date or inaccurate. Croy doesn’t cite his sources and sometimes passes anecdotal information as tried and tested truth. Although written with much more authority than many of the era’s movie fan magazine fare, the book tends to present the author’s opinions without much critical thought or further examination.

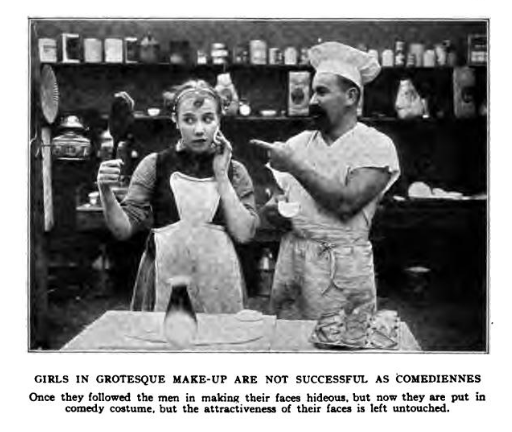

Several assertions made by the author are plain silly. For instance, in the comedy chapter, the author matter-of-factly states that because women can never be funny as men most producers relegate “female players in burlesque to have beauty parts, with the acrobatics left to the men”. Apparently, the man wasn’t a huge fan of Mabel Normand. Or Alice Howell, or Leotine, or Miss Drew, or Florence Lawrence, or literally any funny female comedian of the era. He even has the audacity to place a picture of Louise Fazenda in the middle of anti-comedienne screed.

One fascinating aspect of the book was the lack of specific references to individual films. Today it’s par for the course that any academic, popular, or biographical film book reference numerous films accompanied by the film year’s release. Croy instead simply refers to films as ‘one popular motion picture’ or ‘I once saw a picture that..’ making it difficult to ascertain which film he is referring to and whether it survives for modern viewing.

Considering past films weren’t readable and available for personal viewing this shouldn’t be a surprise but I was a bit disappointed not to hear what films that early on had entered the canon only after a couple decades of movies. Luckily from Croy’s sparse descriptions, I was able to identify some films discussed such as the below picture from the totally bonkers 1917 film A Mormon Maid shown below or an in-depth explanation of the 1906 trick film The Motorist?.

Croy finishes the book with a chapter on the future of the motion picture industry. He predicts quite accurately that in the coming years, mechanical improvements will bring about more complex lighting setups, more realism onscreen, and the frequent employment of motion pictures in the classroom teaching students a wide array of subjects.

In his estimation, color pictures—not talking pictures—will stand as the greatest achievement of cinema in the forthcoming years. Predicting that inventors will in the not-so-distant future accurately reproduce synchronized sound with film, Croy estimates that it’ll prove to be a passing fade as viewers won’t want the spoken word to ruin the illusion of the fanciful worlds created onscreen. Even if he is no Nostradamus, his musing over the power of cinema beautifully captures the allure of silent movies that last today:

The chief source of interest in motion pictures is the constant stimulation they are the means of furnishing to the brain by the fact that part of the story is left out. The mind is stimulated into interpreting the action of the performers on the screen and applying their motives and anticipating their actions more by the fact that the words are missing than if the word were audible.

The observer supplies his own words, in his own language, and after his own manner of thought, as art in its highest form always causes an observer to do…With the words unspoken, the observer enters into the play and imagines himself a participator more than if some omniscient machine supplied them. Without the words he is free; he interprets the actions as befits his age, experience and philosophy.

How Motion Pictures Are Made inaccuracies and occasional dim-sighted views don’t detract from the knowledge contained or the enjoyment of reading this time capsule of 1910s cinema. The book provides us with the perspective of those who experienced firsthand cinema’s early evolution as they began to write the first histories of the young medium.

Anyone interested in the early filmmaking practices employed will no doubt find this an unrivaled well of knowledge long since forgotten as the generation of pioneering technicians of the trade passed away. Untouched by both the disdain for silent films after the coming of sound or the nostalgia of later generations, How the Motion Pictures Are Made comes as close as possible to transporting us to the earliest days of Hollywood filmmaking.

This is my third of six reviews for the 2023 Classic Film Reading Challenge sponsored by Raquel Stecher of Out of the Past. Make sure to subscribe to my email list to get my next summer reading challenge review straight to your inbox:

What an excellent review — despite its flaws, this certainly sounds like a fascinating read, Shawn! I liked seeing the “how it’s done” photos. So funny, though, that the author didn’t mention specific films. I’d love to know the rationale behind that. And I had to laugh at his assertion that women could never be as funny in films as men. This was a great pick for your challenge!

— Karen