1916 marked the 300th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. Naturally, motion picture studios celebrated the occasion by releasing a flurry of Shakespeare adaptations from The Merchant of Venice to Macbeth.

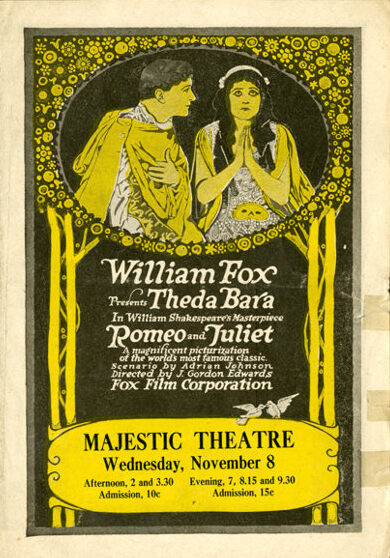

In the case of Romeo and Juliet, two adaptations were released the very same week in late October. Metro Pictures produced one adaptation starring its biggest star couple Francis X. Bushman and Beverly Bayne while the Fox Film Corporation made one starring Theda Bara.

According to the recent documentary This is Francis X. Bushman, Metro had spent considerable money and time to produce a world-class adaptation of the Shakespeare classic only for William Fox to quickly put together his own slightly shorter production to try and ride the wave to sales. Conventional wisdom is that Metro’s adaptation was more successful thanks to its better production values than the rushed Fox adaptation.

Count me skeptical but such a simple victory told by Bushman’s recollections might not be the most reliable way to assess these two respective silent adaptations. Requiring a bit of detective work since both films remain lost, I dig up several reviews and news items to uncover a much more complicated narrative and a fascinating look at the century-old problem of movie studios stepping on each others’ toes.

Screen and real-life couple Francis X. Bushman and Beverly Bayne.

Outfoxing Metro

Unlike many of the early movie moguls who regularly involved themselves in the daily production of their films, William Fox was known much more as an office-bound, shrewd businessman than one who actively visited writing rooms and shooting sets.

Founding the Fox Film Corporation in 1915 a decade after owning his first Nickelodeon, Fox’s business strategy consisted of creating bankable stars and putting them in a high number of mid-budget programmers, increasing the chance of striking a big hit without carrying a large risk. Upon the surprise success of Theda Bara’s vehicle A Fool There Was (1915), Fox used this strategy to amass huge profits with Bara in numerous affordable projects playing her notorious vamp character.

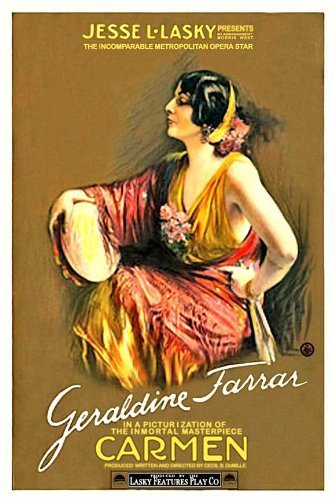

Like any good movie producer, Fox never brushed his nose at a surefire publicity opportunity. Upon hearing opera star Geraldine Farrar signed with Cecil B. DeMille to star in a 1915 adaptation of Carmen, young director Raoul Walsh suggested to William Fox that, in the words of DeMille biographer Scott Eyman, Fox let him “do a quick knockoff version with Fox star Theda Barta and scoop the Demille version”. Legend has it that two days later they were shooting on already existing sets in their Fort Lee studios.

Both Carmens were released in November of that year getting concurrent reviews in the same papers and sometimes even on the same page! While critics mostly agreed that DeMille’s and Farrar’s version was more entertaining and a better adaptation of the original novel (see Moving Picture World review for one example), Fox had successfully made a profit, using the competing films to drum up free publicity and inviting people to see both to compare. 1915’s Barbenheimer if I may.

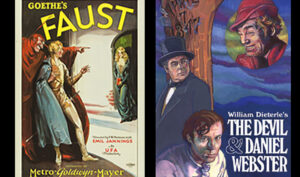

(Left) Poster for Cecil B. DeMille’s Carmen. (Right) Poster for Raoul Walsh’s Carmen.

It’s no surprise that Fox repeated this same strategy the following year after Metro announced its two biggest stars Francis X. Bushman and Beverly Bayne were starring in an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. Fox would pick Theda Bara again to star as the titular role in his copycat film although Juliet proved to be a larger departure from her vamp character than Carmen did.

Reading several movie magazines in the months following up to the release of both Romeo and Juliet films in late October 1916, it’s clear that Metro’s adaptation was months in the making. Metro planted plenty of news stories about the production in movie magazines playing up its large budget and commitment to accurately portraying the spirit of Shakespeare in their film.

Moving Picture World reported that “its leading players are Shakespearean actors and actresses of world-wide reputation… [with] many of them having starred in Shakespearean parts, and nearly every member of the cast has had a classical training”. Its reported $35,000 costume budget and $250,000 total budget, a behemoth in the early years of feature films, let everyone know Romeo and Juliet would be Metro’s centerpiece of its fall program.

(Left) Metro’s Romeo and Juliet Poster. (Right) Fox’s Romeo and Juliet Poster.

Following weeks of movie magazines discussing the writing and shooting of Bushman’s Romeo and Juliet, the earliest mention of Fox’s version in Wid’s Daily is a short announcement in their September 21 issue, “Fox is planning to do “Romeo and Juliet” with Theda Bara. They horned in on Farrar’s ‘Carmen’ and will now try to cop Metro’s ‘Romeo’ publicity” (p. 703).

Within a month of this announcement, both versions were opening in theaters across the country. Motography detailed the success of two theaters only separated by a few buildings in Dallas had great success both running one of the competing adaptations at the same time.

In its article Two Romeos Playing Texas, Motography explained that in the weeks proceeding the films’ releases, “several exhibitors having either the one or the other booked, began to get anxious about his competition booking the other; but the same is true as was the result with both “Carmen’s”—business for each film version has been greater than it would probably have been otherwise” (p. 1081).

(Left) Francis X. Bushman and Beverly Bayne in Metro’s Romeo and Juliet. (Right) Theda Bara and Harry Hilliard in Fox’s Romeo and Juliet.

Not all theater exhibitors were happy however with the two dueling films. After extolling the virtues of Bushman’s version, theater owner George Madison in Motography complained:

I made money on this feature but not as much as I should have and in view of the fact that William Fox of the Fox Film Corporation, in an advertisement in Motography, invited exhibitors to comment on their preference between this production and the one made by his organization, you may place me on record as saying that the Fox production served but one purpose, that of making the exhibitor’s problem more complicated than it already is.

I can see no valid reason why the exhibitor should be made to bear the costs of any internal strife which might be in progress between these two manufacturing companies.

Dec 16, 1916, p. 1313

Other theater owners disliked even the idea of costume dramas at all, arguing they had fallen out of favor with their audience. S. Trinz, a theater owner claiming to serve the ‘better classes” bluntly stated:

Personally, I feel that if there had never been a Romeo and Juliet picture made, all concerned would have been none the loser. People simply do not want costume plays and I can’t figure out why two producers should be breaking their necks to make this one… The stars and not the production were the attraction.

Motography Nov 25, 1916, p. 1162

Despite the naysayers, William Fox’s gambit worked for him again at the box office. But did he fail, as he did with Walsh’s Carmen the previous year, to gain the critical praise of the original production?

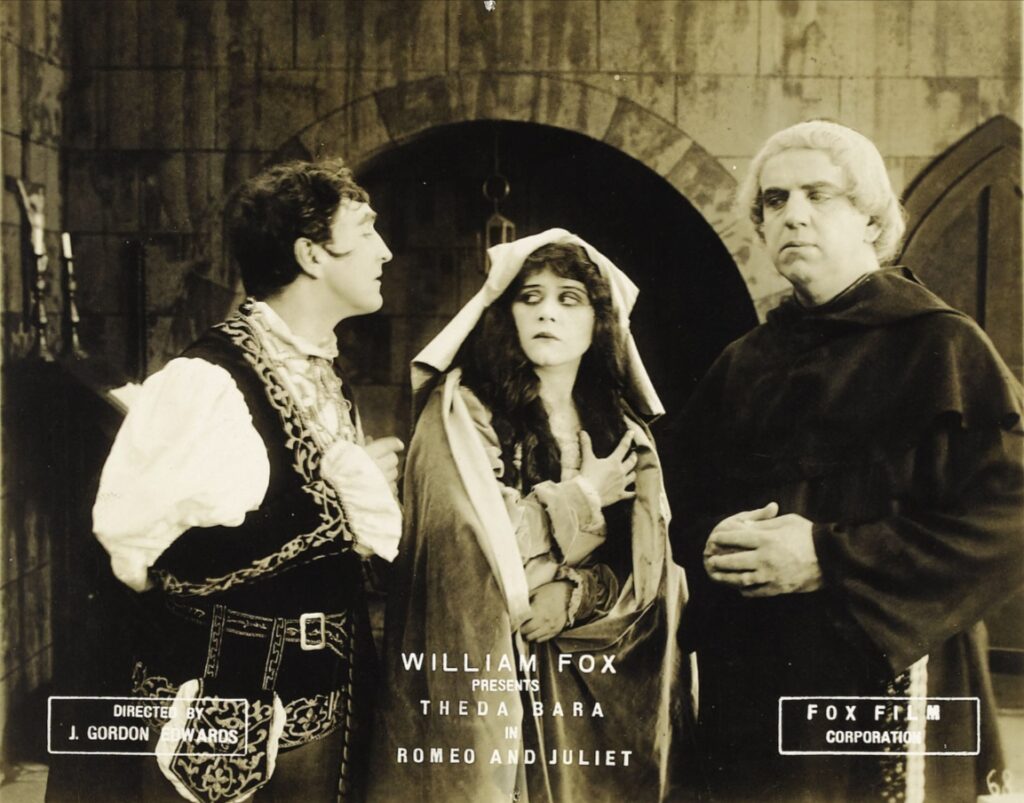

Promotional still for Fox’s Romeo and Juliet.

To Art or Not to Art

Coming out the exact same week, both versions were frequently reviewed side-by-side in the majority of the movie magazines. Critics and theater owners themselves were divided over which version was better, a much more favorable outcome for Fox than in the previous year’s Carmen bout.

Everyone agreed that Metro’s production was the more ambitious of the two adaptations. Taking thirteen weeks to film, every actor spoke Shakespearean lines in front of the camera hoping to have the appropriate atmosphere on set and to remain authentic even for lipreaders in the audience.

For the film’s October 19 premiere at the Broadway theater, two classically trained musicians wrote a score with “motifs for each of the chief characters… and special musical settings which blend perfectly with the situations presented” (Moving Picture World, Oct 28, 1916, p. 531). Lifting pieces from Gonoud’s operatic version and Tschiacovsky’s symphony version of Romeo and Juliet, the composers sought to match the filmmaker’s attempt to make their moving picture high art.

Critics in love with Bushman’s Romeo and Juliet pointed to its authenticity and artistic grandeur as its finest achievements. Motorgarphy proclaimed that “it is the first time the real spirit of Shakespeare has been successfully interpreted in motion pictures” (Nov 4, 1916, p. 1017).

Moving Picture World, declaring the film “easily will rank with the best kinematographic efforts”, lauded the creators who managed to “visualize the story of the world’s greatest love tragedy just as it was penned by the hand of the master [and] have neither subtracted from it in any essential detail nor have they added to it” (Nov 4, 1916, p. 685).

Metro’s version boasted 600 actors and expertly constructed sets.

Even in the most congratulatory reviews, it is easy to see elements of the film that would turn off a lot of people. In their rave, Variety admits that “the film has an unusual amount of titles”, although they assure their readers that this is a benefit to the picture providing so much of the Bard’s written words onscreen. Bushman’s version sought to include every act of the play, running at eight reels or around two hours of running time.

Wid’s Daily took issue with the slow pace of the film declaring in all caps: BIG IMPRESSIVE THEATRIC STAGING TOO SLOW AND TOO MUCH ROMEO. Although giving the production credit for impressive sets and a large cast, the reviewer stated that the fatal error of the production was its inability to frame and light the actors clearly enough to capture their emotions for the audience. Citing a notable lack of close-ups, the reviewer demurred that “the characters in this film, instead of being red-blooded humans, seemed to be actors upon the stage” (Oct 26, 1916, p. 1052).

Immediately following this review of Metro’s Romeo and Juliet, Wid’s praises Fox’s adaptation as a CLASSIC MADE HUMAN AND ENTERTAINING BY DIRECTION. The reviewer admits that he isn’t particularly a big fan of Shakespeare’s theatrical adaptations and remained skeptical that the medium of film could be an adequate medium for such a story.

Praising the film’s expert use of lighting, staging, and editing, the reviewer assures their readers that Fox’s adaptation “moves with a dramatic tempo which compels interest and has been produced by a director who understands the possibilities of the camera in bringing his characters into intimate contact with the audience” (Oct 26, 1916, p. 1053).

Even in the ads, there are several examples of tightly framed shots in Fox’s Romeo and Juliet (Motion Picture News Oct 21, 1916, p. 2533)

Variety, although more favorable to Metro’s version, agrees with Wid’s prognosis that the Fox film caters well to those more averse to Shakespeare and is “very likely to strike a popular note that a more serious effort might miss”. They further expound on the difference between the two versions:

The picture is put forward frankly to please them [Theda Bara fans] and without any great pretentions to artistic purpose… Not that the director has taken any rude liberties with the classic, for he has followed the play fairly evenly, but every artitifce, such as “close ups” and holding Juliet in the conspicuous position of the picture to centre attention upon her, is employed to emphasize the star.

Miss Bara’s followers will doubtless find this arrangement satisfactory, but it does take something rom the sincerity of the effort to ‘bring Shakespeare to the people’…the differenece between the two [adaptations] is typical. The Metro version is finer artistry—artistry being one of the things of which the cinema is in need, and the Fox version one with the more obvious theatrical “punch” of which the screen has had no lack.

Oct 26, 1916, p. 1053

Simply put, the Metro version considered itself high art, aiming to reproduce the feeling and atmosphere of a Shakespeare theatrical play onscreen. The Fox version saw itself more as entertainment for everyone. Personally having seen my fair share of theatric adaptations in the early 1910s, I’d prefer to see Fox’s more dynamic ninety-minute adaptation than Metro’s more serious-minded, proscenium-POV, two-hour extravaganza.

It’d be hard to pass up seeing Theda Bara playing an innocent ingenue, especially compared to her other surviving roles. Of course, I wouldn’t stick my nose up at watching the Metro version if it was everyone found simply to see one of the biggest screen couples of the era.

The climactic finale of Metro’s high-minded Romeo and Juliet.

Two Adaptations, Both Alike in Quality

Given the different opinions expressed in contemporary reviews, it’s fair to say that while Metro’s Romeo and Juliet appealed to more ‘cultured’ viewers, the Fox version proved to be more than just a cheaply made knockoff. Of course, William Fox probably cared more about the film’s box office receipts than whether critics actually thought his company’s film qualified as high art. Wid’s Daily at the opening of their laudatory review for Fox’s version admits:

Surface indications would suggest that “Bill” Fox decided to do “Bill” Shakespeare’s classic—after learning that some one else was working on it. That sort of thing has been done before by different people, but, even though that might be the case, we’ll certainly have to give Mr. Fox credit for going out and making a real production when he did start.

Oct 26, 1916, p. 1053

It certainly wasn’t the last time two studios competed head-to-head at the box office with similar movies or adaptations at the same time (A Bug’s Life and Antz, Armageddon and Deep Impact, White House Down and Olympus Has Fallen to name a few modern examples). To the studios and theaters, a flurry of competing versions might be a massive headache but proves an opportunity for the average fan to find an adaptation to enjoy.

In 1916, classical Shakespeare fans could enjoy Bushman’s high-art, theatrically staged Romeo and Juliet while a couple of blocks away casual theatergoers could enjoy the more zippy, modern Fox version. And of course, as attested by Wid’s Daily reviewer, fans debated and compared the two versions just as much as the critics and theater exhibitors:

I believe, however, that we will have a repetition of the “Carmen” situation, with wild-eyed discussion by the people, who have made up their minds before they saw either film, which one they were going to like; each insisting that the other is wrong after they have seen both films, the net result being that they will both do record-breaking business.

As a sample of the way in which some people judge this sort of a thing, I can tell you that in leaving the theatre I heard one lady remark, “Oh, but hasn’t Mr. Bushman such awful pretty legs!” There will be some who will know before they go to see the film that Mr. Bushman is going to be a wonderful Romeo.

Oct 26, 1916, p. 1053

Sounds an awful lot like modern theatergoing albeit with Marvel and DC rather than Fox and Metro or Bushman and Bara! Unfortunately, we’ll never be able to argue over the merits of either 1916 Romeo and Juliet until they appear in someone’s attic or in the depths of the archives. Until then we’ll have to make do with competing new releases and find solace in the fact that even after a hundred years some things never change all that much in Hollywood.

This post is a part of Silver Screen Classic’s 2023 Classic Literature on Film Blogathon. Visit the blogathon’s main page to read other great reviews of cinematic adaptations of literature’s finest works.

Interesting to see how little Hollywood has changed in this regard. Even so, it’s a shame both films are lost. It would be a treat to see either one!

The press around the Metro version sounds a lot like the hoopla around the 1936 MGM Romeo and Juliet with Norma Shearer and Leslie Howard– a lot of stress on the movie being “high art” and true to Shakespeare. I’m with you– I’d probably prefer the Bara version. I love Shakespeare, but the best Shakespearean films tend to take more liberties.

I want my Shakespeare either scene for scene like Branagh’s gargantuan Hamlet or a loose adaptation. Most things in between are usually gonna be better onstage.

Fascinating! There was definitely more to Theda Bara than the vamp thing–it would be interesting to see her play Juliet.

Thank you for this interesting and informative post, Shawn. It’s a shame that these films are lost. I certainly wouldn’t mind seeing Theda Bara as Juliet. Thank you, also, for mentioning the Francis X. Bushman documentary — I’d love to see it.

Thanks! They played the doc on TCM a little while ago so I bet it’ll show up again sometime soon. I’d only seen him as Massala in Ben-Hur so excited to watch his surviving films when he was at his height as a star in the teens.