Film censorship is almost as old as film itself. By the 1910s in America, several states had stringent film censorship boards that would review films and cut out parts deemed to be immoral. After a litany of Hollywood scandals in the early 1920s, calls for government censorship grew louder from a small portion of the American public. Censored: The Private Life of the Movies was published in 1930, the same year the Production Code’s list of “Do’s and Don’ts” was officially adopted by the Motion Picture Producers and Directors Association. While the code would not be stringently enforced until 1934, strict censorship at the time seemed only like a matter of time in the American film industry.

ACLU lawyer Morris Leopold Ernest and film critic Pare Lorentz use Censored to expose how corrupt and inefficient American film censorship was in 1930. The book is very grounded in current events being much more concerned with the current state of censorship instead of its history. The authors hoped that exposing the ridiculousness of censorship would help encourage people to try to stop what they saw as the inevitable march towards more censorship at the expense of freedom of speech.

The most fascinating part of the book was the author’s detailed descriptions of the six major state censorship boards in a chapter snidely titled ‘The Saints at Work’. The authors break down who makes up each state board, whether it be politicians, volunteers, or religious leaders, and describe their system for censoring films. Each state board had a different personality and its own pet peeves: New York was terrified of depictions of political corruption, Maryland stuck its nose up at kisses on the neck, and Kansas stood ready with scissors whenever characters were shown drinking alcohol.

Apparently, this scene from Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) was too steamy for Maryland audiences.

Using films from 1930 and the late 1920s, the authors include specific cuts each state censorship board ordered or requested for specific films. I was surprised by the number of films mentioned that I was familiar with and loved. For instance, I couldn’t imagine that anyone would be as audacious as to cut Murnau’s silent masterpiece Sunrise. But that is exactly what the Maryland board did! The board ordered the beautiful scene between the husband and the city girl lying together in the weeds near the murky swamp to be cut before screening in the state. My heart goes out to whoever had to see even a slightly truncated Sunrise in Maryland or any other state.

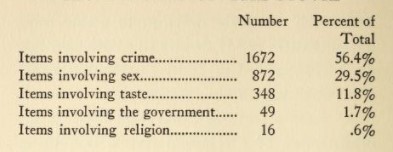

Alongside various examples of cuts these boards would make, the authors include an informative graph that tracks the reason behind each cut (pictured below). While it only shows films censored in 1928, it is fascinating to see what state censorship boards were most concerned about. While I generally thought that sex and violence were the main culprits, I was surprised by how many cuts were made related to crime. I also have no idea what nose-thumbing refers to or why it was seen as such a big deal.

A breakdown of the number and percentage of the reasons for why a film was cut or edited in 1928.

Building upon the specific examples of cuts, Ernest and Lorentz succinctly contextualize how the movie industry had become beholden to censorship. For them, Hollywood was a well-oiled machine brought to their knees by religious activists and local chapters of women’s organizations for the almighty dollar. Speaking of the top Hollywood brass, they surmise that:

These men are bound to protect their companies, to increase production. Any deviation from the movies of the leading political party or the leading church means trouble. And trouble cuts down sale. Theirs is a simple formula.

Page 193

Unlike our fearful authors, freedom of speech and the press mean nothing to those in charge of producing and bankrolling the movies. Money incentivized the studios to submit themselves to censorship without much of a fight. Money also would incentivize Hollywood to standardize the censorship process by creating the Production Code Office instead of following the arbitrary rules and varying morals of different state censorship boards.

Besides the in-depth information about the state censorship boards and its snapshot view of censorship in 1930, the book really falls flat. The authors grandstand for too much of the book, dragging censorship through the mud without saying anything novel about why we shouldn’t do it. Reading the book long after the decline of the Production Code, it reads more as a historical relic of 1930s America than a useful argument against censorship. Luckily the authors littered the book with their fair share of snarky comments to make the more fluffy parts of the book still entertaining to read.

If you’re curious to hear an anti-censorship perspective in 1930 America or lists of edits made to late silent films and early talkies, Censored is a fine book to check out. If that doesn’t sound too interesting, I’d recommend spending your time instead enjoying a Pre-Code film with the full satisfaction that the state board of Pennsylvania would be very disappointed in you watching a film full of over-passionate lovemaking, vulgar dancing, and worst of all nose-thumbing.

I’ve included a few of my favorite snarky comments from the book for your own enjoyment:

This book review is part of the 2021 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge hosted by Raquel Stecher’s Out of the Past blog. Check out all my classic film book reviews and great reviews from others participating in this summer’s challenge.