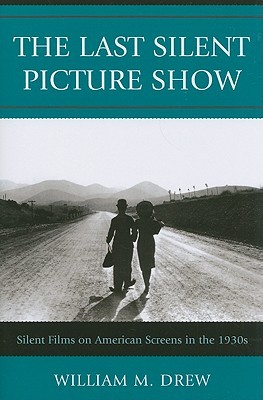

The transition from silent pictures to all-talking and all-talking sound films is often told as a simplistic narrative: The Jazz Singer‘s success in 1927 revolutionized Hollywood as studios scrambled to convert their studios and theaters to sound as quickly as possible. William M. Drew’s The Last Picture Show complicates this narrative as he examines silent films’ continued existence in 1930s America. He makes extensive use of contemporary reviewers and columnists to explore the film industry and its audience’s relationship with silent films in the early days of the talking picture.

In The Last Picture Show, Drew charts silent film’s transition from the dominant style of filmmaking in the late 1920s to becoming a special event relegated to tent shows, arthouse theaters, and university classrooms by the end of the 1930s. While Hollywood fully embraced the sound film by 1930, Drew shows the voices in the film industry that hoped silent films could continue alongside talkies in some form.

For instance, the documentary The Silent Enemy in 1930 and Murnau’s Tabu and Chaplin’s City Lights in 1931 proved if well-made or connected to strong screen personas, silent films could garner positive reviews and modest box office returns. The early chapters are littered with quotes from contemporary critics, industry insiders, and stars arguing that silents could and should play a role in a cinematic landscape dominated by sound, a thought inconsistent with the simple teleological narrative of Hollywood’s fast transition to talking pictures we often tell today.

The Silent Enemy was advertised as an educational experience to persuade a curious public to venture to see a silent film in 1930.

Despite some calls for the continuation of the silent tradition, it became clear by 1931 that Hollywood studios saw little potential in creating new silent films or even routinely re-releasing silents in their back catalog with synchronized scores and sound effects. Drew examines the various venues where silent films continued to appear on American screens throughout the rest of the 1930s.

In the early 1930s, theaters that could not afford to upgrade to sound, mostly found in rural areas, continued showing previously released silent films or the silent versions of recent sound films. As these silent theaters went out of business or were lucky enough to scrape up the money to convert to sound by the mid-1930s, silents films circulated in marginalized and non-traditional spaces from left-wing political organizations screening revolutionary Soviet pictures to local theaters in Little Tokyos and Chinatowns showing Chinese and Japanese silent films. By the end of the 1930s, silent film screenings resided almost exclusively in educational venues fueled by the efforts of private collectors and newly founded film archives such as Iris Barry’s collection at the Museum of Modern Art.

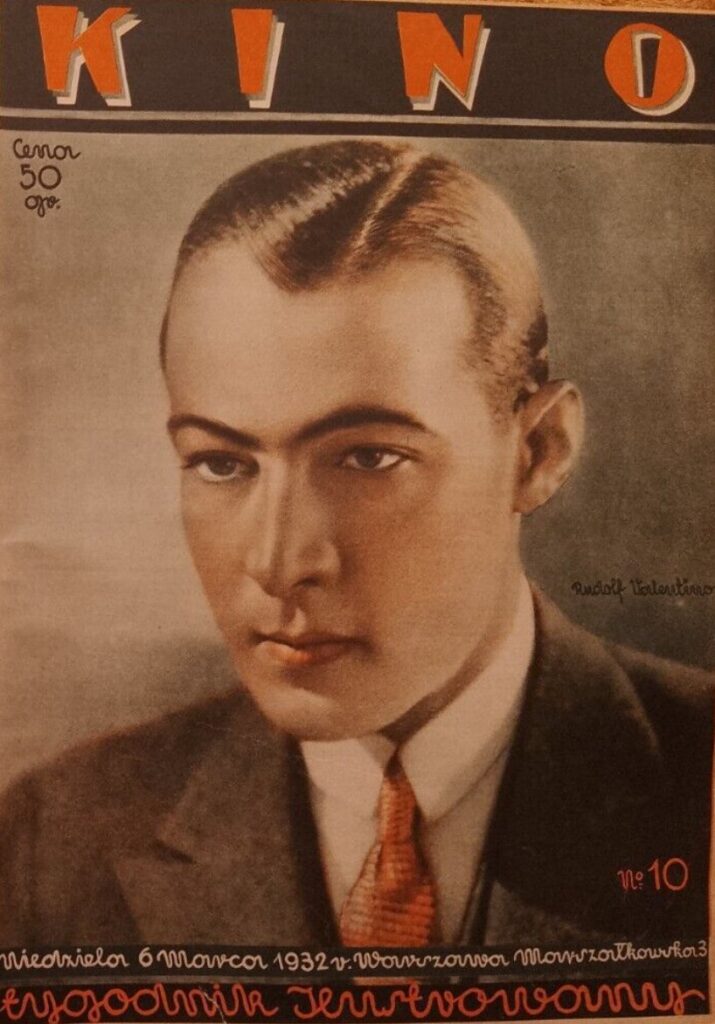

As The Last Picture Show moves through each of the various venues where silent films continued to be screened in the 1930s, he pays special attention to how audiences reacted to these films. He includes quotes from snooty critics looking down on silent films to promote new sound pictures, passionate Valentino fans happy to see their favorite matinee idol on the silver screen again, younger audiences unimpressed at re-releases of yesteryear’s classic silent hits, and newly immigrated Americans enjoying films produced in their home country and native language. It becomes clear very early on in the book that the response to silent films in the 1930s and beyond remained mixed despite the studios’ dismissive attitude towards its older films.

As a silent film fan, it was quite refreshing to hear 1930s Americans who cherished films from the silent era. It always amazed and saddened me to read so many accounts from moviegoers, stars, and industry insiders that bashed on the silent films they themselves had watched, made, and enjoyed only a few years after sound films entered the scene. Drew balances these derogatory voices with positive reactions to silent films screened. For every negative review of a silent re-issue or account of a rambunctious, disrespectful crowd at a MOMA screening, Drew includes accounts of Valentino youth fan clubs into the late 1930s and reviews praising re-released and foreign-made silent films in the 1930s. Drew’s discussion of mid-1930s silent masterpieces from Soviet, Chinese, and Japanese made me excited to check out more silent films produced abroad in the 1930s as well as revisit some of my favorite silent classics that attracted 1930s American viewers.

Valentino remained a popular name long after his death as shown by this 1932 cover for a Polish fan magazine six years after Valentino’s death.

One of the most fascinating, and admittedly depressing, aspects of The Last Picture Show is its attempt to provide context to the negative attitude towards silent films in the 1930s. As maddening as it is to read accounts of studios neglecting, discarding, or sometimes destroying their silent films, Drew helps to contextualize these decisions and indecision although it never could quite take the sting away from thinking all the films we’ve lost from the era. As early as 1920, theater exhibitors held The Old Time Movie Show, a program of Nickelodeon era films screened for the audience to laugh at the film’s crude filmmaking. (Just imagine if today we screened early 2000s films to make fun of their ‘primitive’ filmmaking styles!)

This attitude of mocking past films as primitive, outdated, and worthy of ridicule first introduced in the silent era only accelerated when Hollywood studios and theater exhibitioners sought to cash in on the sound film’s triumph by contrasting it with the days of silent filmmaking. In many ways, the battle wasn’t so much silent vs. talkie but old vs. new. Even with organized efforts to save and preserve films for future generations, the personal prejudices and blindspots of archivists and collectors with the best of intentions still managed to fail to save a large portion of the silent era. Look no further than Iris Barry’s disregard for American silent blockbusters and genre pictures in her MOMA collection.

Despite the gut-wrenching accounts of studios burning their films or letting them rot in an uncontrolled storage area, the book ends on a positive note. Drew argues that the total lack of disrespect the industry had for the silent era motivated numerous film aficionados around the world to save the studios’ films themselves and get serious about film preservation. As collectors and archivists successfully preserved silent films and screened them for audiences, films of the previous era became worthy of respect instead of objects of laughter and ridicule. Today’s current film culture of respecting and revisiting classic films, despite some detractors, owes a lot to the pioneers of the film preservation movement.

Overall, The Last Picture Show‘s fascinating look at a subject largely forgotten by history is a must-read for silent film fanatics and anyone in love with films from the 1930s.

This book review is part of the 2021 Summer Reading Classic Film Book Challenge hosted by Raquel Stecher’s Out of the Past blog. Check out all my classic film book reviews and great reviews from others participating in this summer’s challenge.