Anyone with experience watching classic films has undoubtedly been taken out of an otherwise engaging, entertaining viewing experience when a film swerves into a heavy dose of racism against African Americans. Even well-made and still remembered Hollywood films like The Lost World (1925), Swing Time (1936), and Gone with the Wind (1939) feature jarringly racist depictions of subservient, dumb black servants, uncomfortably long blackface musical numbers, and/or glorification of Jim Crow southern life.

While even the general public is aware of the most egregious examples of racism found in films such as Birth of A Nation (1915), most aren’t familiar with the many creatives working inside and outside the Hollywood system who fought to create realistic and sympathetic African American characters and stories. Whether in independently financed vehicles produced by black directors and producers or in big-budget Hollywood pictures helmed by white directors and producers, there are numerous classic films that aimed to change a less-than-flattering image of African Americans onscreen.

In celebration of African American history month, let’s celebrate the films, filmmakers, and stars that went against the grain to create realistic, empathetic screen portrayals of African American culture and life that set the foundation for many influential modern black filmmakers and actors. Here are ten great classic films with compelling African American characters:

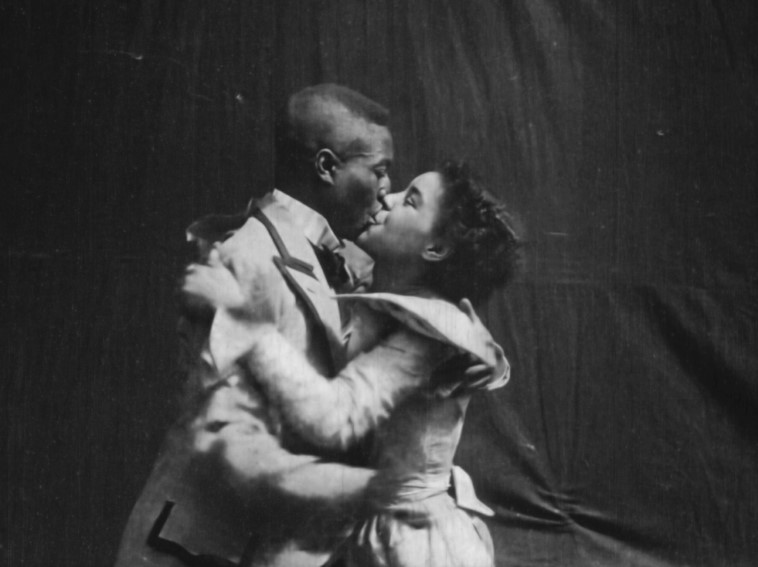

Something Good—Negro Kiss (1898)

Stage performers Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown share a brief smooch.

Early film is brimming with some of the most obtuse and jarring racist depictions of African Americans; however, in 2018 at the USC film archive, this less-than-a-minute-long film emerged showing a young couple sharing a passionate kiss. An updated version of 1896’s The Kiss, Something Good doesn’t rely on exaggerations and stereotypes that many films of the 1890s and 1900s employed. Instead, we share the joy of the two young black performers sharing a kiss, beautifully capturing the feeling of young love for the earliest screen audiences.

Within Our Gates (1920)

A brutally realistic flashback brilliantly reverses A Birth of Nation‘s depictions of predatory black men.

Creator of the earliest surviving feature-length film directed by an African American, Chicago-based Oscar Micheaux overcame budgetary restraints to produce, write, and direct this searing tale of racism in early 20th century America. Within Our Gates follows Sylvia, a black school teacher struggling to find benefactors for her severely underfunded all-black school. Through Sylvia’s quest to gain funding from largely white socialites and memories of her own traumatic upbringing, Mischeaux exposes us to varying levels of racism, antipathy, and sympathy amongst both white and black characters.

Numerous state and local censorship boards threatened to suppress or dramatically cut the film, largely over a jarring depiction of a black man’s lynching at the hands of white farmers. Thought lost for decades, the film was recovered in a Spanish archive in the 1970s and restored by the Library of Congress. More than a century later, Within Our Gates stands as a gripping and devastating look at various forms of racism that black Americans experienced decades before the Civil Rights Movement.

Flying Ace (1926)

Shot in Florida, the film has a distinctive look compared to Hollywood pictures of the era.

While Mischeux’s hard-hitting films critiquing 20th-century American racism are more well-known today, several independent filmmakers produced light-hearted pictures primarily created for segregated black theaters in the Southern United States. The Norman Studios’ The Flying Ace is one such ‘race’ film with an all-black cast that centers on an escapist tale of romance and drama.

The Flying Ace provided black audiences with a chance to see themselves depicted in an easy-breezy fun adventure film. For example, the film’s main character is an African American World War I pilot even though only white men were allowed to fly in the United States Army at the time. It remains an entertaining feature film filled with optimism that allowed black audiences to look hopefully to the opportunities that lay ahead once in a less predujiced future.

Imitation of Life (1934)

Business partners and friends Delilah (Louise Beaver) and Bea (Claudette Colbert).

Nominated for Best Picture at the seventh Oscars, Imitation of Life received critical acclaim portraying a friendship between a black and white single mother who rise up the social ladder after founding their own restaurant chain. The black woman’s storyline receives equal dramatic weight compared to her white partner. Louise Beaver, one of the most talented sought-out black actresses in 1930s Hollywood, shines in one of her rare roles more substantiative than her usual maid and mammy characters foisted upon her by the studios.

Rare for studio-produced Hollywood films of the era, Imitation of Life frankly examines racial identity. A central subplot revolves around Bea’s daughter, playing by Fredi Washington, struggling to accept her black identity as a lighter-skinned woman able to pass as white. While the white woman’s romance sucks out most of the dramatic tension in the latter part of the film, Imitation of Life stands as a fascinating character study of race in Great Depression-era America.

Of Mice and Men (1939)

Crooks (Leigh Whipper) Lenny (Lon Chaney Jr.) bond over their social isolation.

This adaptation of Steinbeck’s classic novella easily could have written out Crooks, a black ranchhand; yet, director Lewis Milestone and actor Leigh Whipper bring this character to life in a key scene. Forced to live in a solitary hut separate from the ranch’s white workers, Crooks connects with Lenny on a personal level as two social outcasts, frankly discussing Crook’ss loneliness from being excluded simply due to his skin color.

Released in the same year as Gone with the Wind, Milestone’s humanistic, if brief, depiction of a black working man devoid of the stereotypes common in Hollywood at the time shows an alternative path available to classic filmmakers that too many bothered to take.

Stormy Weather (1943)

Bill Robinson, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway in a publicity still for the film

After the explosion of jazz as an artistic movement in the 1920s, mainstream white American culture became increasingly infatuated with black music and culture. To capitalize on this interest in white audiences and to cash in on revenue from segregated black movie houses, Hollywood studios produced a select number of all-black films filled with popular black musicians and celebrities.

One such film, Stormy Weather uses a loosely structured backstage romance to highlight nearly a dozen of the era’s most talented and popular African American performers and musicians. With appearances from tap dancer Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinso, jazz legend Fats Waller, and Cab Calloway and his band the film easily sweeps you with its vast amount of talent, catchy songs, and extraordinary dance numbers, most notably the jaw-dropping dance number performed by the acrobatic Nicolas Brothers in the film’s final scene.

Lifeboat (1944)

Survivors of a German U-Boat attack in Hitchcock’s Lifeboat.

In the spirit of togetherness, Hollywood films during World War II softened the image of their black characters onscreen. War-time films like Sahara and Bataan (both 1943) depicted black soldiers in racially diverse military units working alongside their white compatriots as equals devoid of the genteel southern slang all too often imposed on black characters at the time.

Of these World War II films, Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) best stands the test of time. A group of Americans during World War II are stranded with a German prisoner on a lifeboat in the middle of the ocean after their boat has been sunk by German submarines. Actor Canada Lee portrays the only black member of the group Joe Spencer. Spencer plays an integral part through the film’s runtime, proving to be just as vital as any other member of the lifeboat in their struggle for survival.

Moonrise (1948)

Rex Ingram was one of the more prolific black actors in classic Hollywood.

Hollywood in the post-World War II era gradually gave more substantial roles to African American performers. During this era, the deep-voiced Rex Ingram, who originally got his start playing stereotyped native characters during the silent era, took advantage of the increase of less stereotyped roles slowly being written in mainstream Hollywood productions.

The best of his performances is in a supporting role in director Frank Borzage’s late-career success Moonrise. While the role leans heavily into the magical negro trope of an elderly black man acting as the spiritual guide to a central white character, Ingram imbues in the character a humanity and charismatic charm that perfectly matches director Frank Borzage‘s mystical dramatic style.

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959)

The racist Earl (Robert Ryan) and Johnny (Harry Belafonte) butt heads while planning a bank heist.

By the end of the 1950s, black stars proved that they could headline major studio films and successfully crossover to white audiences. The charismatic Harry Belafonte does just that opposite Robert Ryan in the film noir Odds Against Tomorrow. Centered on a bank heist carried out by a black man working together with a vehemently racist man played by Robert Ryan, the film highlights Ryan’s insecurity as the root cause of his racial prejudice.

Working as a well-tuned bank heist, the film expertly integrates mid-20th-century race relations into the mix without sacrificing the entertainment value of the film. Contemporary audiences also recognized the film for its timely themes, gaining a nomination in the short-lived Golden Globes award for Best Film for Promoting International Understanding.

A Raisin in the Sun (1961)

The Younger family fiercely debate whether moving into the white suburbs is worth the opposition they’ll face.

The 1960s breathed new life into numerous African American careers in front of and behind the camera as the Civil Rights Movement gained nationwide attention and Hollywood’s Production Code gradually loosened. Adapted from Lorraine Hansberry’s award-winning play, Daniel Petrie’s A Raisin in the Sun features a star-studded all-black cast headlined by Syndey Poiter and Ruby Dee.

A captivating drama, A Raisin in the Sun centers on the Younger family’s debate amongst themselves as they decide how to best use their grandmother’s $10,000 insurance policy. Featuring multiple black perspectives from male and female, young and old, brash and meek characters, the film captures the variety of 1960s black Americans’ struggles, personalities, and dreams. Poiter, on the cusp of becoming one of America’s greatest movie stars, and the rest of the cast create dynamic, three-dimensional characters that both manage to break your heart and capture your empathy despite their flaws and insecurities.

l really enjoyed this excellent post, Shawn! Both Flying Ace and Within Our Gates are included in a box set I received for Christmas, and I am looking so forward to watching this both. I was glad to see Odds Against Tomorrow included; it’s such an excellent film in so many ways. I was so surprised to read about that Golden Globe category. I need to give Moonrise a rewatch, too — I haven’t seen it in more than 20 years! Thanks for this first-rate write-up on these outstanding performances.

Thanks! Within Our Gates and The Flying Ace would be a fascinating double feature for sure.