With only a small handful of Easter related films, DeMille is easily the director most associated with the holiday. A lot of that has to do with the longevity of his 1956 remake of his silent epic The Ten Commandments which ABC has aired on Easter weekend for fifty years.

Another reason for DeMille’s Easter supremacy is his penchant for historical epics heavily tied to religious subjects. DeMille himself was quite aware of his own close ties to Biblical and Apocryphal stories, calling The Ten Commandments (1923), The King of Kings (1927), and The Sign of the Cross (1932) his Biblical trilogy.

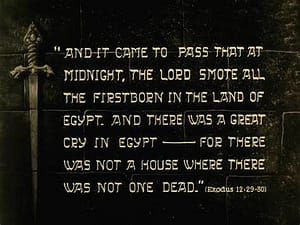

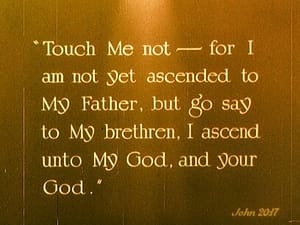

The Ten Commandments and The King of Kings relied heavily upon the Bible ripping verses straight out of the Old and New Testament to serve as title cards. The Sign of the Cross, the only sound film of the trilogy, stands out as an adaption of William Barret’s popular 1895 stage play of the same name. Despite the popularity of the play and its 1914 screen adaptation, audiences had much less familiarity with The Sign of the Cross’s plot allowing DeMille more flexibility to change the story to his liking.

Title cards in The Ten Commandments (left) and The King of Kings (right) go as far as citing which Bible verse the text originally came from.

The major plotline of the film follows the Prefect of Rome Marcus Superbus (Frederic March) who falls in love with a Christian woman Mercia (Elissa Landi) and works to free her from Nero’s (Charles Laughton) extermination decree. Empress Poppaea (Claudette Colbert) meanwhile unsuccessfully seduces Marcus and eggs on Nero’s persecution of the Christians to punish Marcus for rejecting her advances.

The Sign of the Cross is easily one of the wildest, most sexually frank films of the Pre-Code era. Local censor boards had a field day cutting out scenes including Colbert bathing nude in goat milk, decapitations, a sensual lesbian dance, and lions eating a naked woman covered partially by flowers.

I wasn’t kidding when I said Pre-Code.

The original 19th century stage play was much more saccharine and largely aimed to strengthen a Christain audience’s own faith. The playwright’s daughter Dorothea Barrett told a British newspaper upon the film’s release that:

Ever since my father’s death I have done my utmost to guard against irreverent presentations of The Sign of the Cross. I have the very strongest views on how it should be produced. It should not on any account be done as a grandiose spectacle. As little money as possible should be spent on it, and the scenery and costumes should be as simple as they can be.

The Citizen, 31 January 1933

Barrett’s took umbrage both with what she saw as DeMille’s irreverent portrayals of sex and violence and with his trademark glamorous costumes and sets. Just like modern audiences who drudge up the film to watch the shocking Pre-Codeness of the film, Barrett focuses solely on what she found offensive overlooking DeMille’s positive portrayal of the early Christians. There is a lot more going on than merely DeMille wanting to show off numerous scantily clad women (although he very much wanted to do so).

DeMille explained the film’s message when contextualizing it with the two previous entries in his Biblical trilogy:

The Ten Commandments is the giving of the law. The King of Kings was the interpretation of the law, the fulfillment of its promise. The Sign of the Cross will be the preservation of the law, the struggle of humanity to live up to it.

Cecil B. DeMille: The Art of the Hollywood Epic by Mark A. Viera & Cecilia DeMille Presley

Interestingly enough, the film does not show much struggle amongst the small Christain community to live the law given in The Ten Commandments and reinterpreted in The King of Kings. Other than some doubts over dying for their faith, The Sign of the Cross is not extremely interested in the individual Christain characters’ conflict with living up to the law.

Instead of showing the virtues of Christain philosophy through individualized conflict, DeMille investigates this struggle through the stark juxtaposition between the Romans’ and Christians’ behavior and ideology. The Romans clothe themselves in fancy togas and expensive jewelry; the Christians wear cheap, humble sackcloth. The Romans battle for power and manipulate each other seeking power and domination; the Christians form a loving community to find peace in the face of persecution. The Romans waste an absorbent amount of goods and labor to decorate their palaces and fill their baths with goat milk; the Christians scrape by and place little value on worldly possessions. The Romans torture and kill for sport; the Christians willing die for eternal salvation rather than fight.

One Roman’s entertainment is another Christian’s torture.

The contrast between the lascivious Romans and the pious Christians presents two distinct paths for humanity to follow. Although the film’s characters remain convinced of the invincibility of Roman philosophy and imperial might—Marcus tells Mercia that “Rome and mankind will go on as they are forever; your Christianity will be stamped out and dead within a year”—the audience know quite well the fate of Christianity and the Romans in the ensuing centuries. We can stomach a tragic ending knowing that humanity wouldn’t always be doomed to follow the Romans’ basest desires of gluttony, pride, and lust.

DeMille’s approach to portray two warring philosophies rather than individualized conflict of faith led him to change the character arc of Marcus Superbus. Unlike the original play, Marcus never converts to Christianity and remains motivated only solely through his love for Mercia. Depending on an audience members’ interpretation of the film, Marcus’ love for Mercia could simply be completely out of lust; however, Marcus could plausibly love Mercia because of her Christian lifestyle and humility that he never found in any of his Roman female companions.

While DeMille’s slight changes to the story and themes of the original play make for a more nuanced portrayal of faith, it also introduces its own problems. Take the ending for instance. SPOILERS Keeping the ending from the play, Marcus and Mercia walk hand in hand to their deaths at the hands of lions for an impatient crowd at the Coliseum. The original ending, Marcus becoming a martyr, is a much stronger motivation to give up own’s life than for a woman one meet only several days before.

Before meeting their death, Marcus tells Mercia that “I believe in you, not this Christ”. The Christians Marcus dies alongside with have complete faith in an eternal award awaiting their gruesome deaths. Marcus simply walks to his death on the odd chance that there is an afterlife where he can be with Mercia. Even for a notorious Roman womanizer, that is a whole new level of horniness only possible in a DeMille film. END SPOILERS

Now this couple has definitely got some sex appeal to them!

If the leads had off-the-chart chemistry we could perhaps overlook this rather weak plot point. Unfortunately though, March and Landis fail to bring much life to DeMille’s typically grandiose dialogue and never convey much passion into the onscreen relationship. Marcus might say he is completely enraptured with Mercia but we as the audience never feel this passion he flowerily describes.

This lack of strong emotion is also a problem for the Christian characters in general. Because the only conflict is simply a matter of survival and not an internal struggle to live up to revolutionary religious philosophy, the Christians feel less like individuals and more like a generic portrayal of everything good. It’s hard to care for a bunch of faceless individuals dressed in unassuming clothing after being introduced to a devilish Nero and a slinking Empress decked to the nines with jewels and personality. Every time Marcus is amongst the Christians, the film drags a bit.

And perhaps this is the most fatal flaw of DeMille’s approach. Juxtaposing the Romans and Christians isn’t entirely successful because of how delicious the Romans are. The violence adequately demonizes the bloodthirsty Romans in contrast to the longsuffering Christians who just want to practice their religion of peace uninterrupted; however, the salacious Romans provides the bulk of the film’s entertainment and shock value while the Christians provide no such magnetism. Perhaps this strategy would work for a 1930s audience repulsed by frank displays of sexuality. As a modern audience though you can’t expect us to vilify a whole group of people because they wear revealing clothing and enjoy more orgies than your average person.

We clearly needed more screentime from Nero, Charles Laughton’s first American screen appearance.

Even if though The Sign of the Cross doesn’t successfully throw all our support and interest into the Christians, you have to appreciate a change of pace from previous early Christain dramas. Simple Christian conversions are a dime a plenty in Hollywood, take Vincius’ conversion in the various versions Quo Vadis for another epic taking place in Nero’s Rome. I can forgive some of the issues with the film largely because DeMille wasn’t afraid to inject his own vision into the story and swing for the fences.

At worst, The Sign of the Cross, is a bloated historical epic with little splashes of some of the most shocking Pre-Code scenes of sex and violence. At best, it is a nuanced portrayal of humanity’s struggle to live up to a higher, nobler purpose. Whichever side you land on, it’s easy to see the film as a signature DeMille vehicle that highlights his ability to craft films with a little bit of everything for everybody.

A Motion Picture Herald ad for Paramount 1932’s offerings.