To deepen my knowledge of the silent era on the European continent, I created the European Silent Cinema Project. I review two European silent films each year starting in 1895 and ending in 1930. Visit the project’s main page for a comprehensive list of films and reviews.

Film #1: Mr. Delaware and the Boxing Kangaroo (Das boxende Känguruh)

Director: Max Skladanowsky

Country: Germany

Film #2: Jumping the Blanket (Le saut à la couverture)

Director: Louis Lumiere

Country: France

The invention of cinema can’t be claimed by any one person or country. Cinema as we know it took decades of technological advancements and dozens of inventors, businessmen, and entrepreneurs to fully develop early film technology into a well-oiled, international industry. 19th-century advancements in film technology such as the Lantham loop, Maltese cross, or flexible and durable celluloid film were invented and created by early pioneers of cinema largely concentrated in the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

Perhaps the most important development in the formative years of cinema was none other than the film projector. Before 1895, the greatest commercial success of film exhibition was Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope, a device that allowed one viewer at a time to see a rotating loop of about 20 seconds of film for a few cents. Kinetoscope parlors did decent business in the United States and in select European cities in late 1894 and early 1895, making Edison and his company hopeful of their device’s financial potential.

While Edison was busy producing short films in his Black Maria film studio to supply his Kinetoscopes, American and European inventors and entertainers alike were busy creating film projectors that could show films for large groups of people. Perhaps Europe could have achieved the act of film projection years earlier if not for the mysterious disappearance of the oft-forgotten father of cinema Louis Le Prince.

It is often repeated that the French Lumiere brothers were the first in the world to project moving picture film to a paying audience but there were several public screenings on both sides of the Atlantic prior to their famed December 28th, 1895 show. (For the earliest known paying audience to see a projected moving-picture show, look no further than the Lanthams and the Eidoloscope). One of those who projected films to a paying audience before the Lumieres was another set of European brothers who worked in Germany.

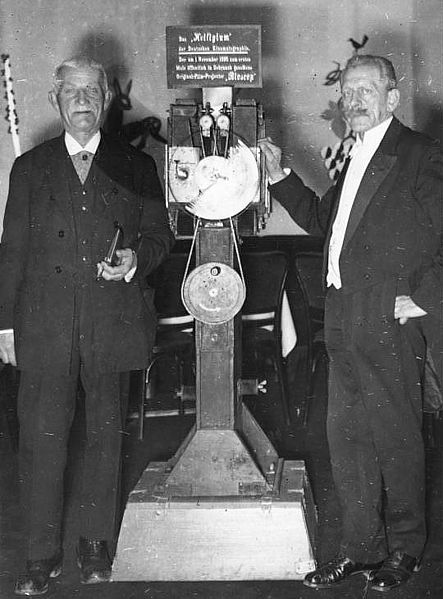

The Skladanowsky brothers with the Bioskop in 1934

Max and Emile Skladanowsky screened a program of a handful of their own films in Berlin’s Wintergarden Ballroom on November 1, 1895, as part of a three-hour mixed variety nightly program. Originally working as magic lantern showmen with their father Carl, Max and Emilie turned their attention to adding films to their program. Max handmade his own camera by 1894 and invented a film projector he dubbed the Bioskop.

The camera used perforation-less 44.5 mm wide celluloid film produced by the Eastman company while the projector utilized two lenses that resembled dissolving magic lantern devices that Max had previously worked with. In order to run the films on the two-lensed projector, the brothers had to cut every other image onto one reel and the other half of the images onto a second reel. The two reels would run simultaneously with each lens alternatively projecting one frame at a time to achieve the illusion of movement onscreen.

While the technologically complicated Bioskop failed to catch on and the Skladanowksy brothers only made a couple dozen of films in the mid-1890s, their early output of films is worth a closer look. Their films more closely resemble Edison’s Black Maria output than the Lumiere brothers’ early actualities with many of their films capturing popular vaudeville performances.

The subject of the Skladanowsky brothers’ films shown in their first public exhibition of the Bioskop included scenes of a traditional Italian peasants’ dance, a wrestling match, a juggler, and a Russian dance. The films were mostly shot in front of a white background that perhaps may have been a sheet draped behind the action. One has to wonder if the Skladanowsky brothers were influenced by and had seen Edison’s films at a Berlin kinetoscope that had arrived in March of 1895, two months before they started filming on their own.

Mr. Delaware and the Boxing Kangaroo

My favorite of their 1895 films is just one of many examples of boxing in early film. Instead of two cats boxing each other in the 1894 Edison film, a man takes on a kangaroo, each of them donning gloves for the bout. Besides showing that animal cruelty laws in entertainment have dramatically improved since 1895, this highlights early’s film connection with other entertainment genres prevalent in the 19th century. The simple framing of the film, full-body shots of the subjects against a plain, white background, mirrors the ideal framing seen in a theater’s front-row seats.

Attention is fully centered on the man and the kangaroo for the audience to fully appreciate the spectacle. Even though the shadows falling behind the boxers onto the white background indicate that the film was most likely shot outside in daylight, the Skladanowsky brothers still decided to frame their subjects to mirror a front-row view in a theater. The theatric framing calls attention to the fact that what we are watching is not just a natural occurrence but is the product of skill and showmanship.

The Skladanowsky brothers are just one set of numerous motion picture technology pioneers in the early and mid-1890s who created and used their own cameras or projectors but failed to create substantial business for their efforts or achieve much more than a footnote or an aside in film history textbooks.

While names like Max and Emile Skladanowksy, Otay Lantham, or William Friese-Greene may be vaguely familiar to a few, the Lumiere brothers are the most recognized figures in early cinema history, only rivaled by Thomas Edison and George Melies. Originally photographers, Louis and Auguste Lumiere turned their efforts to creating moving pictures after their invention of the cinematograph. The machine, patented on February 15, 1895, could record, develop, and project films and was small and light enough to carry around with relative ease.

The early Lumiere films provide a different vision than the canned vaudeville routines offered by Thomas Edison and the Skladanowsky brothers. A major distinction is the lively backgrounds of the 1895 Lumiere films. Instead of white sheets or dark black backdrops framing the films’ subjects, these films captured the everyday backgrounds of busy people walking about, waves crashing against the ocean shore, and leaves blowing in the wind.

Audiences ecstatically responded to seeing leaves blow in the wind in the background of the Lumiere brothers’ 1895 film Baby’s Meal.

The Lumieres’ subjects onscreen are aware that a camera is observing their actions just like Edison’s and the Skladanowskys brothers’ vaudeville performers are; however, the Lumiere subjects are acting out real-life events instead of following a previous stage routine. It is perhaps these blurred lines of actuality and performativity that have crowned the Lumieres’ early films as the face of the birth of cinema and continue to stand as engaging and fascinating documents of the 1890s over a century later.

Of the ten films shown at the Lumiere brothers’ first paying audience on December 28, 1895, in Le Salon Indien du Grande Café, only Cordeliers’ Square in Lyon can be considered a snapshot of everyday life, capturing people as if the camera is not watching and recording their actions.

The rest of the films involve subjects who, if not minutely directed by the cameraman such as in one of the first narrative fiction films The Sprinkler Gets Sprinkled, are at least aware of the camera. In these films, the subjects are performing specifically for and towards not just the cameraman but to the film’s future audience as well.

Jumping Onto the Blanket, the eighth film shown in the program demonstrates how these early Lumiere films blur the lines between actuality and performativity. The film features four men holding a blanket, one onlooker, and a man trying to jump into the blanket and perform some sort of flip. At first glance, the film looks like a vaudeville routine being performed outside; however, as the man runs towards the blanket, he fails at his attempt. It takes him a couple more tries to jump into the blanket and successfully perform a flip. The film ends with the man having failed a subsequent flip and being bounced up and down by the men holding the blanket.

Jumping Onto the Blanket

There is no denying the men were framed to fit inside the camera’s vision. The Lumieres simply didn’t just happen upon six men in the countryside playing around and asked to film them. Despite the film’s staged nature, it feels free of routine or plan. It seems as if the cameraman placed the men in their positions to stay inside the camera’s sight and set them loose to record their actions, even accepting failed attempts and deviations in the original plan. We become not concerned with the man’s success but the process, his failures and successes, finding a way to enjoy them both.

The Lumiere brothers captured scenes not from the stage but from everyday life instead, creating a new genre of media instead of capturing a preexisting form of staged entertainment in a new format. This new language of film sought to expand what subjects could be filmed, inspiring other early European filmmakers like George Melies, Alice Guy-Blache, and R.W. Paul to further develop the newfound medium of film.

The achievement of film projectors by both the Skladanowsky brothers and the Lumiere brothers in 1895 set in motion European cinema’s dominant place in silent film history, beginning nearly a two decades run of worldwide domination and burgeoning innovation. While today these short 1895 films of boxing kangaroos and blanket acrobatics seem primitive, both their technological advancements and aesthetic choices are central to understanding the development of cinema in Europe and around the world.