The Hollywood Blacklist in the 1950s really cut short a lot of interesting careers and forced promising talent to relocate to other countries. This is what happened to director Cy Endfield who was just getting some public and critical attention in 1950 with two film noirs, The Underworld Story and The Sound of Fury. Watching these films you can definitely get a sense of why the House of Un-American Activities would have suspected Endfield to be a communist.

Several years ago the Film Noir Foundation and the UCLA Film and Television Archive teamed up to restore The Sound of Fury to bring this forgotten film to light. One of its claims to fame is that is based on the same real story that Fritz Lang’s 1936 film Fury is: the kidnapping and murder of Brooke Hart in 1933. While it comfortably fits into the mold of a cynical, post-war noir, the film unravels in a much different direction than what I thought it would on my first viewing.

The film starts off like many noirs with a man down on his luck. Howard Tyler (Frank Lovejoy) has a wife (Kathleen Ryan) and a child with another on the way he’d like to provide for but he can’t find a job. After hitchhiking around the valley, Howard runs into a man named Jerry (Lloyd Bridges) who can provide him with a job opportunity, albeit a “I’ll pay you in cash” kind of job. Howard reluctantly drives the run-away car for Jerry’s gas station robberies but can now buy premium ham for his family.

So this is what they mean by bringing home the bacon!

The first job Howard assists Jerry in excellently shows our protagonist’s conflicted conscience. Howard pulls the car up across the street from a small gas station and is told by Jerry to keep it in gear. Jerry calmly strolls into the store whistling, ready for some quick easy cash.

Even as Jerry is walking away, the camera stays focused on Howard sitting nervously in the driver’s seat. We see Howard trying to stay calm while breathing heavily. He constantly looks in the mirror and turns his head anxiously every time he hears a honk or a car passing by. He’s clearly torn, trying to decide which is worse: holding up a small gas station to provide for his family or being unemployed and letting his wife and son starve.

We stay fixed on him fidgeting about for almost an entire minute, the audience waiting alongside Howard to see what will happen. When we finally cut to Jerry in the store holding up an elderly couple while pillaging through the cashier, the initial thrill of robbing a store has already passed. The film doesn’t care to show all the fun, slick Jerry is having, instead focusing on Howard’s new life as a reluctant criminal.

Dark frame, dark souls.

Intercut between Howard’s fall into a life of petty crime is the story of a local newspaperman Gil Stanton (Richard Carlson) who is convinced by his boss Hal Clendenning (Art Smith) to cover a string of local robberies for some extra cash. The articles dramatize the crime problem by declaring a “crime wave” in order to sell more papers. Dr. Vito Simone (Renzo Cesana), a house guest of Gil and his wife, is the voice of reason, confronting Gil about his yellow journalist writing and reminding him of his responsibilities to the public.

With Jerry’s ambition to move on to bigger crimes with bigger paydays and Howard’s persistent conscience urging him to quit the business, Jerry decides to carry out one last crime: kidnap a millionaire’s son for a large sum of ransom money. Like in many noirs, the job goes terribly wrong when Jerry decides to kill the millionaire’s son by bashing him in with a rock and dumping his body in the lake against Howard’s best efforts.

The day following the murder, Jerry plans a double date for him and Howard as an alibi to use when they mail the ransom letter. Howard is despondent with his bottled-up conscience only growing as he spends a night with another woman, lying to her about his marital status to stay in character. Despite Jerry’s instructions to relax, Howard stays tense and turns to the bottle for some fleeting comfort. When Howard returns home from his and Jerry’s double date and sees the newspaper headlines announcing the discovery of their victim’s car, he breaks down and confesses to his date from the previous night.

I’m an accomplice to murder!….and I’m also married.

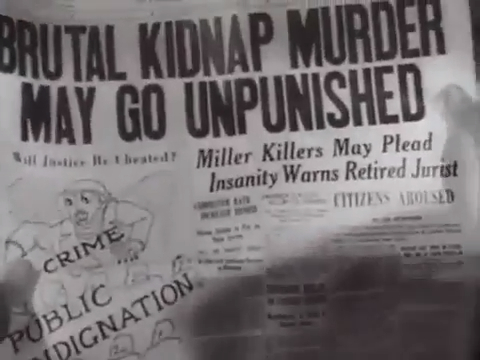

The film takes a sharp turn away from Howard’s personal battle with his conscience. With Howard caught and Jerry on the run, Gil builds up public outrage against the two “monsters” despite local law enforcers and the sheriff telling him to go easy on the reporting and not condemn the men before receiving a fair trial. After a visit from Howard’s wife and a good philosophical talk with Dr. Simone, Gil changes his tune, admitting that he “used words as criminally as they used that rock” and vows to do what he can to make things right.

Gil frantically tries to change his original headline for the upcoming newspaper to something more just and fair. It may already be too late to set the record straight as the crowds have already gathered outside the jail after the law brings Jerry into town. The town has gathered to get justice. If the courts might not punish them, we will.

I could see why Gil might want to change that article!

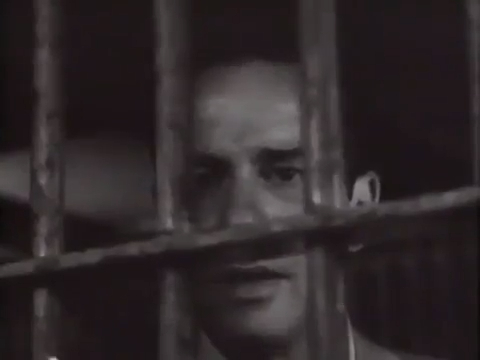

The camera work depicting the growing crowd works beautifully to emphasize the chaos and energy amongst the crowd. Handheld camera shots give this scene a documentary feel, not being afraid of getting close to individuals in the crowd or being in the middle of the action. There is no singular character the camera chooses to focus on, floating between faces in the crowd and their efforts to break through the line of policemen to enact justice on the two monsters being held inside the jail. The crowd shots feel much more like documentary footage from the 1960s protests than anything in the 1950s. The crowd is fed up and will do anything to stand up to the law and justice system to accomplish their task.

Maybe Howard and Jerry aren’t the only ones that should be locked behind bars!

In response to the rowdy crowd, the prison moves all of the inmates besides Jerry and Howard to a different location to keep them out of danger. Gil visits Howard with the chief of police to apologize for his defamatory articles and to offer his helping hand. The sheriff pragmatically informs Howard that they’ll try their best to safeguard them from the mob outside even though it doesn’t look good for him and Jerry.

The police have their hands full guarding the jail with the impatient men and women gathered outside. The men lead a charge into the jail, spraying the police guarding the jail with a pressure hose to break into the jail. The mob knocks out both Jerry and Howard and holds them up to the crowd waiting outside. In their eyes, justice has been served, these murderers receive the same treatment as their victim did.

Gil and Sherrif listening to the sound of fury.

Gil, Hal, and the Sherrif dejectedly listen to the crowd cheer in the aftermath. The sheriff holds back from saying “I told you so” but tells Gil to never forget the sound of the mob. Gil epically vows that he’ll do him one better: he’ll never let the people forget the sound of that night. Hal leaves to print tomorrow’s newspaper, just another day in the journalist business. The camera glides out the window showing us Gil walking off with his wife as a voice-over of Dr. Simone wraps up the film before it fades to black. “Violence is a disease caused by moral and social breakdown. That is the real problem. And it must be solved by reason, not by emotion with understanding not hate.”

Overall the film tackles some interesting material although it is guilty of becoming preachy in parts. The whole character of Dr. Simone has no relevance to the plot and is just an excuse to spoonfeed moral philosophy straight to the audience. Gil doesn’t need a scientist to lecture him on his moral responsibilities as a journalist. His change of heart occurs when he interacts with Mrs. Tyler and learns what type of person Howard is learning in the process that his yellow journalism condemned a good, everyday man who made a string of terrible mistakes.

The film’s transition from focusing on Howard’s struggle with his conscience to devoting its energy to warning its viewers about the media’s role in creating mob mentality is a bit clunky. The last half becomes more concerned with teaching the audience a moral lesson than with what happens to the characters.

For instance, we’re never given a solid reason for the mobs being there. Yeah, the yellow journalism might have riled them up but Donald Miller doesn’t seem like someone they’d rally around. Maybe I’m thinking too Marxist but I don’t know if a brutal murder of a rich kid would rally hoards of people to demand vigilante justice. Maybe that is just me being de-sensitized to violent crime. The transition from Howard as our protagonist to Gil might pull us back from the characters but helps to drive home the critical lens of the film.

Lloyd Bridge’s winning smile

On the positive side, Lloyd Bridges gives a great performance, exuberating with energy and charisma. He perfectly nails an overconfident petty criminal who bites off more than he can chew, believing in himself to pull off a good of a lifetime only to screw it up. Also, the crowd scenes are a great example of early documentary-style filmmaking in narrative features and really help show an effective example of the film’s suspicion of the media and the voice of people, two staples of American democracy.

While not a complete home run, The Sound of Fury is definitely worth a watch for any film noir fan or Communists that are out there.