Aviation and film took the world by storm in the early 20th century. Just eight years after the Lumiere brothers’ famed 1895 projected screenings, Orville and Wilbur Wright took their first flight in December 1903. By the 1910s, film had exploded into an international entertainment industry while aviation had become more reliable and technologically advanced, playing an important role in World War I.

It should be no surprise that the two young, exciting inventions would collide often in the first decades of the 20th century. Filmmakers in the 1910s increasingly began incorporating aeroplanes into their films. Mack Sennet used several for comedic effect while other prestige filmmakers of the 1910s shot aerial footage for wartime dramas. While many of these films showed brief clips of planes taking off and landing, more risky aerial stunts would only become a mainstay in Hollywood films after World War I.

Left: Mabel Normand on a date in the sky in 1912 Biograph comedy A Dash Through the Clouds. Right: Mary Pickford standing next to stunt pilot Glenn Martin in a film still for Allan Dwan’s lost 1915 film The Girl from Yesterday.

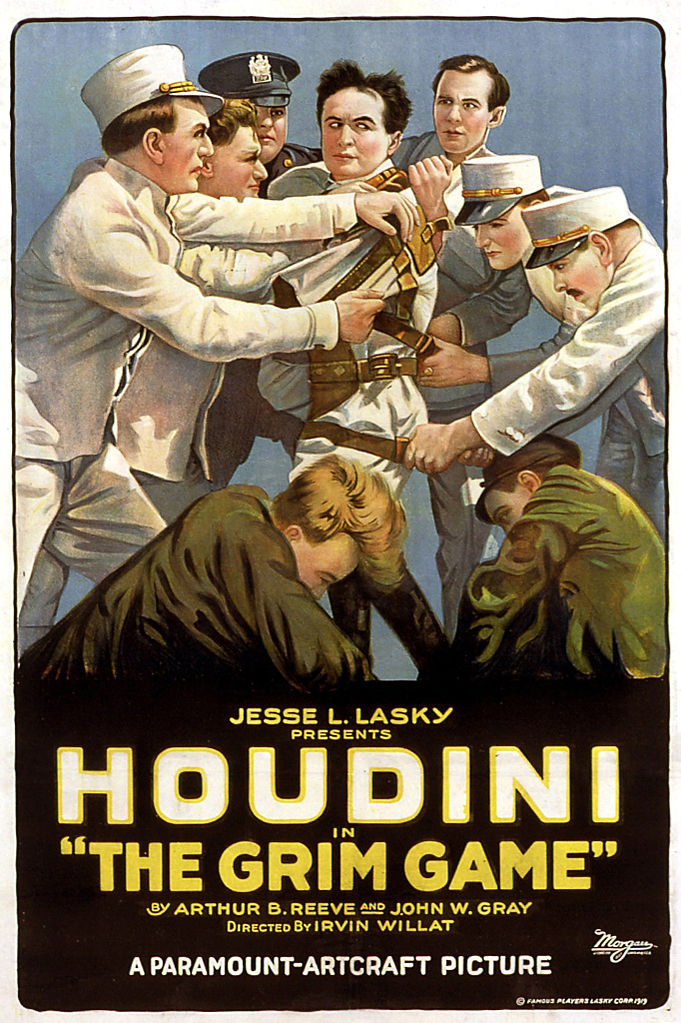

1919’s The Grim Game was one of the first films after the First World War to take advantage of the several hundred stunt aviators touring the country wowing audiences with their death-defying flights. Starring world-famous magician Harry Houdini in his feature film debut, The Grim Game became a media sensation after its scripted aerial stunt almost ended in the death of its two pilots and stuntman. Caught on film and used in the finished product after the script was rewritten, The Grim Game‘s electrifying aerial collision paved the way for dozens of aviation-themed pictures centered around death-defying stunts in the 1920s.

This review of Harry Houdini’s first feature film The Grim Game is part of Taking Up Room‘s Aviation in Film Blogathon. To read other great aviation-themed articles, visit the blogathon’s main page.

Houdini’s Tricks On Ground and In-Air

By the time they started filming in early 1919, Harry Houdini had spent more than a decade as the world’s most famous magician known for his fantastical, highly publicized escape tricks. He had previously incorporated filmed footage of himself in vaudeville acts and had starred in the 1918 serial The Master Mystery. The Grim Game, however, was his first feature film. The film’s plot is heavily aware that people were there to see Houdini in action, giving us several Houdini tricks and escapes.

Right from the get-go our hero Hanford, Harry Houdini’s audacious newspaper reporter, uses his expertise to open a locked door while breaking into his uncle Dudley Cameron’s large estate. A simple trick but a great introduction to the later stunts performed by our protagonist. Hanford is there to see his miserly millionaire uncle’s caretaker Mary. Despite their obvious infatuation for each other, Mr. Cameron has plans to marry off Mary to his doctor Dr. Tyson, in turn giving him the whole Cameron fortune.

Locks won’t stop Harry Houdini!

After setting up our main protagonist and his love interest, the film takes a while before we are treated to another Houdini trick instead getting bogged down in exposition (although there is a short scene when Houdini breaks out of handcuffs that his coworkers place on him as a joke). We learn that Hanford’s boss Clifton Allison owes Cameron a substantial amount of money that is threatening to bankrupt his newspaper The Call. Cameron’s lawyer Richard Raver, close friends with Tyson and Allison, has been secretly siphoning off tons of money from Cameron’s estate.

To save his job and The Call, Hanford devises a scheme to increase the circulation of the newspaper and raise enough money to pay off Cameron once and for all. The plan is to fake Cameron’s death, hide him away in a small cabin in the country for several days, and deliberately leave circumstantial evidence to implicate Hanford as the murderer. After The Call rakes in large profits and increased circulation from having the inside scoop of the murder case, the group would bring Cameron out of hiding to clear Hanford’s name and create an even larger media sensation. When Hanford pitches the idea to Tyson, Allison, and Raver, they all heartily agree, hoping to use the plan to get back at Cameron and settle their own scores with the miser.

At first, the plan works perfectly: the newspaper’s inside scoop on the sensational murder has the town in a frenzy and buying tons of newspapers while Hanford waits in jail. Unfortunately for Hanford, Cameron’s body is unexpectedly found at the bottom of a well as the film dives headfirst into several escape tricks and stunts performed by Houdini.

These guards wouldn’t be laughing if they knew who they were dealing with.

Stuck behind bars without any way to find the real killer to clear his name, Hanford slips out of his handcuffs and a ball and chain, climbs out his window, and down the three-story building. After his recapture, Houdini wriggles out of a straight jacket while hanging over the edge of a six-story building before landing into an awning that breaks his fall, capping off his glorious second escape. Building up to the eventual airborne finale, Houdini also performs several other small stunts, from escaping a bear trap in the woods to climbing out of an underwater trap door.

All previous stunts in the picture pale in comparison to the climactic finale. After being discovered, the real murderer attempts to run away in one of the newspaper’s delivery airplanes. Unbeknownst to the murderer when taking off, Mary was hiding in the passenger seat waiting for Hanford. Hanford rushes to Mary’s rescue, hopping into another plane to save Mary and capture the murderer. Hanford lowers the plane overtop the murderer’s mid-flight and climbs down a rope to land on the plane to save Mary; however, the two planes collide and crash down below. All survive unharmed as the police grab the murderer from the crashed plane’s cockpit. Mary and Hanford live out their lives happily ever after with the Cameron estate all to themselves.

Houdini dangling over on the edge tied to a rope and stuck in a straightjacket.

While Houdini’s stunts are exciting, they must have paled in comparison to seeing him perform live. It feels like his escapes from handcuffs and a straightjacket are rushed perhaps to make sure that he never exposed his techniques to those watching closing. Even if we don’t have time to marvel at the difficulty of Houdini’s tricks, we definitely see glimpses of Houdini’s showmanship, escalating the difficulty of his stunts by adding unique challenges to each. Any amateur magician can escape a straightjacket but what about while hanging upside over the edge of a building?

Houdini also does really well in more traditional movie acrobatics. He convincingly slides under a car and hangs on during his first escape from jail. He shows off his athleticism when hanging from the ceiling to bounce on an unsuspecting hoodlum. Even though some of Houdini’s trademark escapes aren’t as exciting on film because they are too rushed in favor of sticking to the film’s over-the-top plot, most of his tricks land quite well. We might not be wondering how Houdini escapes or worried whether he’ll survive the trick but are still on the edge of our seats. Even if the climatic airplane collision overshadows the rest of the stunts throughout The Grim Game, Houdini proves to be a decent actor with the knowledge of how to transfer his onstage talent and persona onto the screen.

A Grim Stunt Gone Right

Other than being Houdini’s first-star vehicle, The Grim Game is mostly remembered for the story behind its spectacular aerial footage, and rightfully so! The script called for Robert E. Kennedy, Houdini’s stunt double and a former flight instructor in the Air Service, to climb down a rope attached to one plane’s wings and jump onto the top wing of the other plane. The stunt was a variation of the popular traveling stuntman Ormer Locklear’s “Dance of Death” where two pilots would switch planes mid-flight.

Originally scheduled to shoot in the early morning on May 31, 1919, maintenance and camera issues delayed shooting the airborne stunt until the afternoon when a slight wind had picked up that had not been present in the morning. Two stunt planes flew parallel to each other, Kennedy’s flying several feet above the second plane, while a third plane carrying a mounting camera flew alongside the other two planes.

2500 feet above the ground, the two stunt planes struggled to keep a consistent distance, oscillating between six and twenty feet making it difficult for Kennedy to climb down from one plane to the other. During the attempt, Kennedy’s legs came within inches (as seen in the film) of the plane’s propeller. Then:

Just before Kennedy released the rope to drop on Thompson’s top wing, a gust or air pocket caused the two planes to collide. Thompson’s wing tore into Pickup’s landing gear and the two Jennies were entangled. Thompson’s plane turned upside down and swung around until it was almost nose to nose with Pickup’s machine. The pilots cut their engines as the shattered wooden propellers threw bits of wood, metal, and fabric around the sky. With no parachutes, the three flyers fell toward certain death as the enmeshed airplanes continued down in a flat spin. Kennedy dangled in space at the end of the rope while Thompson and Pickup frantically worked their controls in hopes of dislodging the two airplanes. Kennedy closed his eyes and waited for the inevitable end… Approximately one thousand feet above the ground, the centrifugal force of the spin miraculously separated the two airplanes and the pilot regained control.

H. Hugh Wynne, The Motion Picture Stunt Pilots and Hollywood’s Classic Aviation Movies p. 11

Both planes managed to land safely, one near Santa Monica Canyon and the other in a nearby bean field. Both pilots were largely unscathed while Kennedy had only suffered several bruises and minor cuts from being dragged along the ground while still holding desperately onto his rope.

The mid-air collision captured onscreen remains thrilling and breathtaking even one hundred years later. The shots beautifully capture how far away the planes are from the ground as the audience nervously watches. The insert shots of Houdini in the cockpit of a plane clearly shot in a studio don’t take you out of the moment.

Left: Kennedy dangles on a rope as the planes attempt to get into position for his drop. Right: Both planes begin their freefall after a gust of wind causes a crash.

The filmmakers and studio instantly recognized they had their hands on some extraordinary footage. They quickly changed the script to include the spectacular footage of the mid-air collision. Instead of Hanford’s character commandeering the plane to rescue Mary, police manage to seize the murderer amidst the rubble of the crashed planes.

Unfortunately for the brave stunt pilot who barely escaped death, Houdini not Kennedy received exclusive credit for performing the stunt to maximize the public’s interest in the film. Kennedy debated filing a civil suit against the studio before deciding against it due to a lack of funds. Kennedy would continue performing aerial stunts until the 1930s eventually dying a natural death on the ground in 1974.

A small snippet from Variety erroneously claims Houdini performed Kennedy’s stunt, adding a broken arm for dramatic effect.

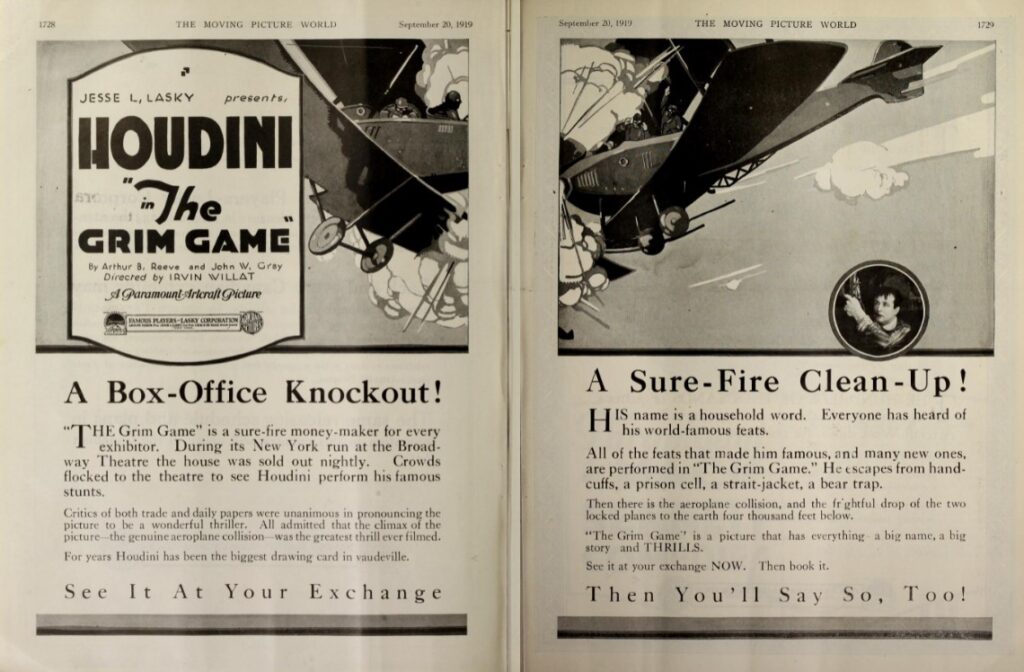

The advertisements leading up to the release of the film capitalized on the stunt, emphasizing the airplane collision over the more traditional escape tricks Houdini performs throughout the film. Many of the ads at the time lauded the airplane stunt as Houdini’s finest trick, even though it wasn’t him dangling from the end of the rope.

Moving Picture World encouraged theater owners to follow the studio’s lead and blend Houdini’s popularity with the sensational colliding aeroplanes. In their weekly advertising aids for theater owners, Moving Picture World instructed theater owners to “above all, boom the airplane smash. Advertise that this is the first real aero accident ever filmed… Tell them that sensation is Houdini’s business, has been for years, but this outdoes anything he ever tried to do because it is an accident”. The public ate up the press and enthusiastically showed up to watch Houdini in his first feature.

Moving Picture World features a full-page ad with a dramatic illustration recreating the film’s climactic mid-air collision.

While The Grim Game was by no means the first film to capitalize on the public’s fascination with aviation, its release and successful aviation-focused advertising campaign encouraged other filmmakers to center entire films on aviation and capture more and more risky, thrilling mid-air stunts. In the ensuing years, films like The Great Air Robbery and The Skywayman both unfortunately now lost, starred famous aerial stunt performers like Ormer Locklear of the day performing their death-defying stunts on film. Such films would build up throughout the 1920s until Wings (1927) and Hell’s Angels (1930) became the ultimate versions of World War I aviation best remembered today. Hairraising aerial stunts would become less prevalent in films over the next decades as aviation became an accepted everyday part of life instead of a novel, exciting invention.

Not only is The Grim Game an important film in the history of aviation onscreen, but is also quite a fun if not sometimes over-the-top star vehicle for Harry Houdini. Even if the spectacular finale stands head and shoulders above the rest of the picture, watching Houdini complete various escapes and tricks is well worth the price of admission. Despite not being the man who risked his life to perform a trick thousands of feet in the air, Houdini successfully performed the admirable trick of transitioning his talents from the stage to the screen.

Whoa, it was nothing short of miraculous that no one was killed attempting that aerial stunt! I guess one of the best tricks of all was the publicity dept. convincing people that Harry himself survived it. Kennedy got the last laugh by surviving into the ’70s. Great stuff!

I just can’t get over the fact that Kennedy survived while hanging from a rope the whole fall!

Another example of what I like to call the “Blog-a-thon Rule of Discovery.” I had no idea this existed, now I must find it!

Whoa! That crash in mid-air! I was holding my breath just reading about it. I’m glad it ended so well, but sorry to hear Kennedy didn’t get the credit he deserved.

I’ll definitely be watching for this film. I’m another one who hadn’t heard of it before.