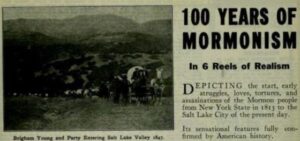

When plucked by Daryl F. Zanuck from Paramount to helm the production of 1940’s Brigham Young, director Henry Hathaway initially told Zanuck that “the two dullest things are wagon trains and religion”. Despite Hathaway’s and others’ correct assertion that the project didn’t scream box office success, Zanuck pushed forward with the historical epic of the Mormon trek westward. Just add Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell to the cast and any concerns about the budget should work itself out, right?

Although a two-hour multi-million dollar epic centered on America’s favorite polygamist Brigham Young seems like a strange project choice to us today, Zanuck’s reasoning doesn’t seem so out there when taking the late 1930s political climate into account. Zanuck and screenwriter Louis Bromfield saw a direct correlation between the persecution of 1930s German Jews with the struggles of 1840s Mormons. Critics certainly took notice and the film received many favorable reviews despite failing to gain a profit for 20th Century Fox.

Promotional poster misleadingly giving top billing to Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell.

If not for devoted fans of Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell, I wonder if Brigham Young would even be remembered today. As someone with a family tree littered with Mormon pioneers, Brigham Young is an endlessly fascinating reflection of the stories and legends I heard ad nauseam growing up in my family and congregation. (And as you can see from my previous blog posts this ain’t my first Mormon movie rodeo.)

Along with the usual review of the film, I’ll dive briefly into the historical angle of it all before ending with a special focus on Linda Darnell’s role in the film. So buckle up, grab a plate of jello and a p of caffeine-free diet Coke, and get ready for the Mormon historical epic of Brigham Young.

Wagon Trains and Religion

While in the later years of the 1930s Zanuck had received a few outlines and treatments for a story centered on 19th-century Mormons, Zanuck committed to the idea following the 1938 success of Vardis Fisher’s Harper-winning novel Children of God that chronicled Mormon history from Joseph Smith’s youth to the present day. Although 20th Century Fox later bought the rights to Fisher’s novel, a non-religious Mormon himself, screenwriters Lamar Trotti and Louis Bromfield crafted their own narrative with heavy involvement from Latter-day Saint leadership’s input.

Brigham Young was a sharp turn from the previous Mormon characters portrayed onscreen. A string of films in the 1910s, which I affectionately call Mormon exploitation films, depicted Mormons as backward, wife-snatching polygamists. Thus the filmmakers had two challenges in producing the film: explaining Mormon history to the average American and gaining audience sympathy for the titular infamous Mormon prophet.

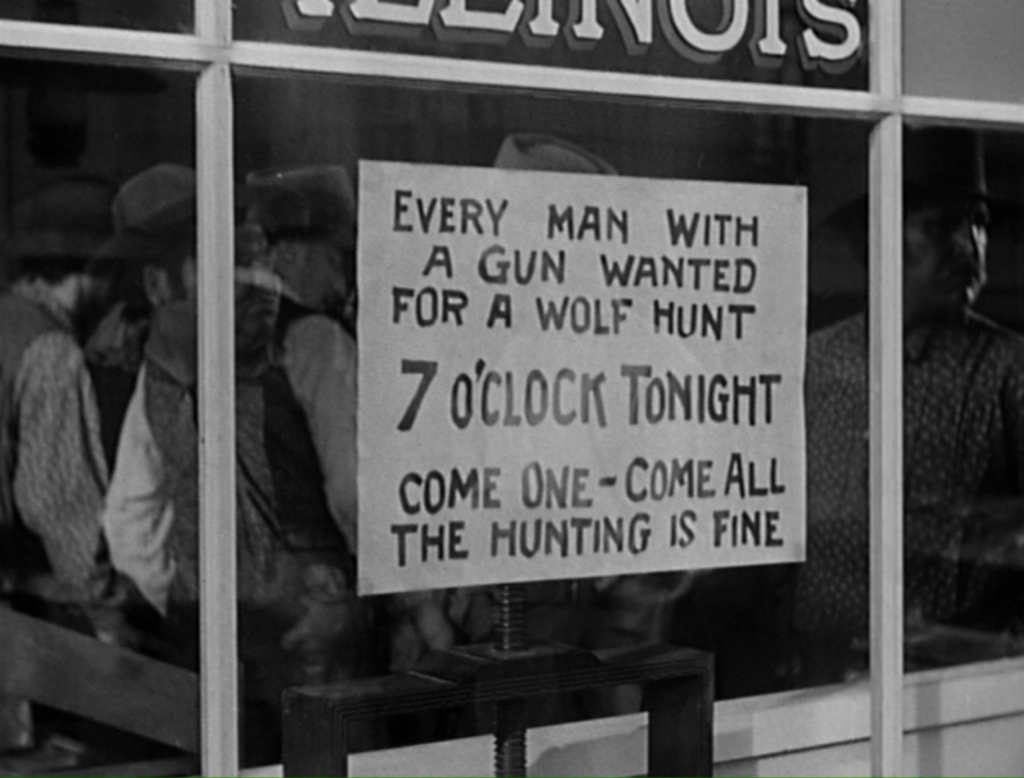

The film succinctly accomplishes both tasks in the opening scenes. Immediately after the opening credits fade, the camera eerily looms into a handwritten sign calling for a town wolf hunt. Cutting to a large group of armed men rubbing their faces with mud, we quickly realize the local Mormons,—not wolves— were the real target of the night’s hunting party.

A signposting inviting the local townsfolk to retaliate against the Mormons.

The men ride up a hill overlooking the Kent residence, a local Mormon family hosting the Webbs, their new non-Mormon neighbors for a family gathering. Zina Webb (Linda Darnell) and Johnathan Kent (Tyrone Power) are hitting it off over a shared affection when the men attack.

The mob shoots Zina’s father in the back, beats Jonathan’s father to death, and burns down the house and barn before riding away into the night. Opening with such a grisly, cold-blooded act of violence squarely places our sympathy with the Kents and their fellow Mormons.

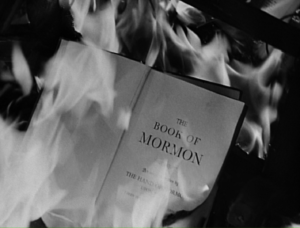

A brief mention of “The Mormon Bible”.

With the hook placed and our lot thrown in squarely with the Mormon people, the film smartly pulls back the scale and sets up key exposition. After Jonathan reports his father’s death to church leaders, we follow Joseph Smith, played by a young Vincent Price, and his top advisors discussing their next steps amidst the string of violence revving up in Nauvoo.

We stay with Smith during a trial for treason as Hollywood once again provides their exposition in a courtroom scene. The prosecuting attorney clearly outlines the local Illinoisians’ griefs with the Mormons: their previous history of controversy in New York, Ohio, and Missouri, the blasphemy of adding additional scripture onto the Bible, and amassing immense political and military power in Illinois.

Here in the courtroom we finally meet the film’s titular character nearly fifteen minutes in. Standing in defense of Joseph Smith in front of the jury, Brigham Young further establishes his own personal ties to Joseph Smith and his reason for believing in Mormonism. Focusing on boilerplate religious aspects that would have largely appealed to the average mid-century Protestant American, Young’s testimony firmly establishes him as a defender of his people’s right to practice their freedom of religion rather than a fierce proponent of polygamy, the most well-known feature of the historical man and his church.

Brigham Young (Dean Jagger) stands up to defend Joseph Smith (Vincent Price) at his treason trial.

By the time of Joseph Smith’s murder and the saints’ subsequent expulsion from Nauvoo, all the key characters and information has been laid down. The only dangling question is whether they’ll ever get around to mentioning polygamy.

Surprisingly, the exposition-filled first half hour of the film stands head and shoulder above the remaining hour and a half of the film’s running time. After the Mormons move out far from the Illinois mobs, the tension built from the violent acts in the first reel immediately dissipates. What starts out as a tight, fast-paced film turns into a rather generic westward expansion movie that only slightly differentiates itself with its Mormon characters and some hints at polygamy.

For the remainder of the film, the main struggle comes as Brigham Young staves off challengers who question his role as Joseph’s successor while leading a large, destitute group of refugees thousands of miles across the American frontier. Meanwhile, Zina and Jonathan work through some slight relationship issues amidst the struggles of adapting first to the rugged Western terrain on the trail and then to the dry environment of the Salt Lake Valley.

Zina and Jonathan traveling on the trail together.

The fact we know going into the film that Brigham Young and his people found long-term success in Utah saps the film from needed dramatic tension. If it didn’t work for them in Salt Lake, I don’t know how you’d explain the dozens of soda chains or double-digit kid families that litter the state of Utah. Brigham Young‘s anti-climactic finale, featuring the much embellished Mormon tale of seagulls rescuing their crops from a horde of crickets, acts as if this simple miracle answers all our lingering questions or solves any conflict that hadn’t been wrapped up over twenty minutes ago.

We can assume Jonathan and Zina get married but have we no idea whether they’ll remain happily together in a monogamous relationship. Brigham finally feels secure in his role as leader but we already felt he was pretty capable once he shepherded his people West. It also doesn’t help that the film leaves off at a point in Mormon history right before things get really interesting.

The Salt Lake Temple circa 1940.

The film ends with shots of then-contemporary Utah with Brigham Young’s voiceover promising to build a great city. The shots of the Salt Lake Valley and the iconic temple come out of nowhere and feel so unearned. mention of the temple Better yet, wouldn’t arriving at the valley have been a more satisfactory dramatic conclusion?

Even if much of Brigham Young fails to entertain its audience much outside of Nauvoo, it has plenty of historic value and oddity to fascinate anyone willing to spend some time with the film.

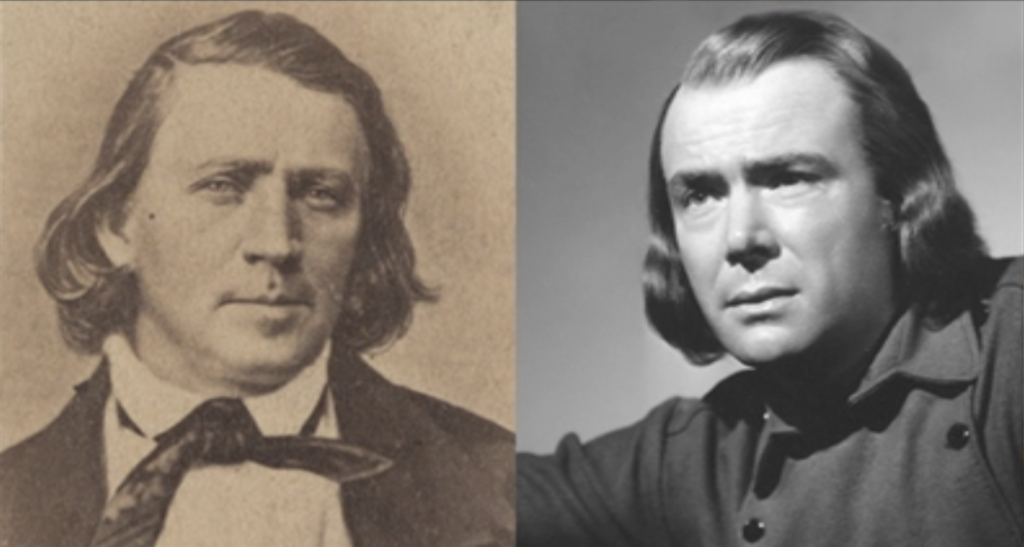

Brigham Young in 1853 at age 52; Dean Jagger in 1940 at age 50.

Brigham Young: Fact or Fiction?

Any history nerd knows Hollywood, especially in the classic era, rarely— if ever—paints a 100% accurate representation of historical events. So it is no surprise Brigham Young occasionally plays loose with the facts.

For instance, the seagulls vs. crickets battle occurred when Brigham Young visited Nebraska in 1848 so he couldn’t have been there to give a stirring speech to the people. Such a simple rearranging of chronology to smooth a narrative out is completely forgivable; however, I hold three major complaints against the film’s portrayal of historical events that either distort or radically change the nature of historical events.

Dean Jagger in costume with the Latter-day Saint liaison to the film George Pyper.

1. Real Brigham Young vs. Reel Brigham Young

By all indications, casting the largely unknown Dean Jagger as Brigham Young proved fortuitous. A church consultant to the film George Pyper, 17 at the time of Brigham Young’s death, remarked that Dean Jagger bore a similar resemblance in looks and manners to the real-life Mormon prophet.

My first issue lies not with Jagger but in how the film paints Young as a timid leader unsure of his standing with God or authority to lead the people. Brigham Young’s doubt in himself wildly contrasts with the real-life figure’s oversized confidence and bombastic public speaking. You don’t get the nickname ‘The Lion of the Lord’ without ruffling a ton of feathers. Just read a few quotes from the man and you’ll get a much more combative, forceful leader than the one portrayed in the film.

Narratively a contrite Brigham works rather well, making him more likable and similar to the everyman persona Price’s Joseph Smith comes off with in the opening act. On the flip side, papering over the power vacuum and chaos created by Smith’s violent murder leaves an opportunity on the table to heighten the dramatic tension of the film’s latter part.

Of course, the film didn’t have time to individually portray the various persons with claims to take Joseph Smith’s self-proclaimed prophetic mantle; however, it definitely shouldn’t have insinuated after Smith’s trial that Joseph tasked Brigham with taking care of the people. Would it have been that hard to include a couple of lines about various groups of Mormons that choose to follow someone other than Brigham Young and head west? (My personal favorite being James Strang, the self-appointed king of Beaver Island).

The Mormons look back at their city shortly after their expulsion.

2. Jews and Mormons: A Faulty Comparison

Since the filmmakers saw a direct link between the contemporary discrimination of Jews in Europe as analogous to the violence perpetuated against Mormons in 1840s, it makes sense to paint the Mormons as pious, pacificists who want to be left alone to worship how and what they may.

But that’s not a great comparison in the first place. Besides both being religious groups facing persecution, the comparison fails flat. The Jews in Europe were systematically being denied rights and killed by their actively anti-Semitic government while Mormons faced mob violence in a frontier climate dominated by states’ rights and a weak federal government. The Nazis deliberately sought out Jews while the American federal government either didn’t think it had the authority to or didn’t care to intervene in a state’s legal or military affairs on behalf of the Mormons.

Clearly, any persecution or violence is a terrible human tragedy but the two religious groups have important distinctions that drastically shift their circumstances and the scale of their plight. For instance, there were legit concerns many non-Mormon Illinoisans had about the ever-growing population of Mormons—who had their own militia not answerable to the state government I might add. The attorney slightly alludes to the local peoples’ fears that the Mormons would vote as a block and make their laws but the film simply dismisses his concerns as the rabid hysteria of the anti-Mormon mobs.

Am I getting lost in the weeds a little bit? Maybe. But I’d argue making the film thematically more about the 1930s European political climate than 1840s Mormon history inserts presentism that fails to tackle the historical events accurately. The story of early Mormonism intersects with tons of fascinating historical developments in American history from the Second Great Awakening to colonial expansion to the shifts in Constitutional law.

I can’t get too upset at anyone trying to mobilize support for the Jews in the days before America entered World War II. At the same time though, Mormon history deserves a more thorough reexamination on a mainstream scale that grapples with both the inspiring and unsavory aspects of both Mormon and American history.

I didn’t know Brigham had a daugh—oh wait a minute…

3. Ducking the Unsavory

Finally, I take issue with how the film papers over the uncomfortable aspects of Mormon history and beliefs. The most obvious example is the fact that Brigham Young feels it can get away with only one scene directly addressing polygamy mixed with a couple of humorous jokes about the practice. I love a great polygamy joke, just look at 1905’s A Trip to Salt Lake City or Raymond Griffith’s 1926 comedy Hands Up! for some great examples, but a biographical picture of America’s biggest proponent of polygamy isn’t the place to simply dismiss polygamy as a harmless joke.

Without inserting a comprehensive thesis on the topic, it’ll suffice to say that heavily encouraging a bunch of traditionally monogamous former Protestants to live polygamously caused a ton of unnecessary heartache, especially for Mormon women. If Brigham Young wants to make its subject an American hero, it better deal with the lasting impact of his polygamous teachings that still negatively affect current Mormons long after the Latter-day Saint church’s discontinuation of the practice in the early 19th century.

Other than polygamy, Brigham Young ignores or downplays the Mormons’ settlement of Ute territory in the Salt Lake Valley, violence perpetrated by various Mormons, and any difference between mainstream Protestantism beyond brief mentions of polygamy. Perhaps the filmmakers didn’t want to risk losing the audience’s sympathies but you can still portray the tragedy of their expulsion from Nauvoo while realistically portraying the society’s troubling aspects. Believe it or not, you don’t have to be completely innocent to be the victim of religiously motivated violence.

I could write an entire tome about Mormon history relating to the film so I’ll leave those wanting a more comprehensive landscape of Nauvoo-era Mormonism to check out the recently published book Kingdom of Nauvoo. These three major complaints I have with Brigham Young‘s portrayal of history should suffice and leave me hopeful one day either on the big or small screen we’ll get a more authentic, realistic retelling of early Mormonism’s history.

Autographed publicity still of Linda Darnell sent to George Pyper.

Linda Darnell vs. Polygamy

Now back to the two big stars from Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell. A lot of modern-day criticism around the film describes Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell as superfluous characters given nothing to do. While it’s true that they get lost under Dean Jagger’s spotlight, I find that Darnell actually plays a key role in the film not just as a box office draw but as the audience surrogate.

The only non-Mormon character involved in the film from beginning to end, Zina’s presence in key scenes allows the Mormon characters to lay exposition down in a natural manner for non-Mormon audiences. For instance, Mrs. Kent (Jane Darwell) explains to Zina while they hide from the mob in the cellar that the men are there simply because of their hatred for Mormons.

At least the publicity stills were a little more forthright about Young’s polygamy than the film.

Zina also has the unenviable position of being the film’s only character to seriously broach the topic of polygamy. Up to this point in the film, there have been various hints at polygamy with Brigham surrounded by several women or his first wife Mary Ann (Mary Astor) almost broaching the subject. The elephant in the room finally appears amidst a fight between Zina and Jonathan before he leaves on a months-long scouting trip ordered by Brigham Young.

In a striking scene that stands out from the rather bland latter part of the picture, Linda Darnell gets the rare chance in the film to shine when Tyrone Power’s character brings up his previous proposal of marriage to her:

Zina: Oh, but your Brigham Young’ll want you to marry a Mormon girl won’t he? Several of them. If you’re gonna be rich, you’ll have to have a lot of wives, won’t you?

I’ve been wonderin’ how you’re gona go about askin’ ’em—one at a time or all together. Maybe it would be easier if you said “Sisters, will you kindly marry me?”

Then after you’ve married 20 or 30 of them suppose you get to lovin’ one more than all the rest put together? Then there’s poor Jonathan, loving one and divided by 30.

Kent: Zina you’re talking nonsense.

Zina: There they’ll be, all darning the same sock an cooking for the same man and all talking about their husband. Just imagine, 30 wives combing your beard!

After listening to Zina’s concerns over his religion and Brigham Young’s orders, Jonathan simply asks about their marriage again and kisses Zina. The screen goes black and we never get an answer from Jonathan or the film about Zina’s questions regarding polygamy. In fact, the next scene features Porter Rockwell (John Carradine) comedically telling Jonathan he plans to marry as many women as possible to birth hoards of Mormon babies as part of his duty to the church.

Even if the film treats polygamy much like parents broaching ‘the talk’ only addressing it quickly out of necessity, this brief scene anchored by Darnell is rather extraordinary. Zina’s questions have a comedic tone to them but with a dark undercurrent. Essentially she asks Jonathan if he will blindly follow his church leaders to the detriment of their relationship. A pretty valid question if you ask me.

Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell sleep in the same wagon divided by “the walls of Jericho”

Whether intentional on behalf of the screenwriters or not, Zina’s line of questioning reflects the documented feelings of many Mormon women who found themselves just one in a parade of wives to their husband. (For those curious you can actually read a compilation of dozens of Mormon polygamous wives’ journals.) The women bore the brunt of the emotional scars of polygamy, constricted by a double standard that too often reduced them to one of many child-bearers and glorified domestic servants.

Even more shockingly accurate, Zina’s assertion that in order to be rich Jonathan would have to marry multiple wives reflects the reality. The majority of polygamous Mormons, around 20% of the religion’s population at the height of polygamy in the 1850s and 1860s, were either wealthy or high-up in church leadership. During the Utah period, Mormon men wanting to be taken seriously as future leaders had to marry multiple women in order to show their faith and gain cache in the community.

Jonathan having a personal relationship with Brigham Young would likely indicate a future in leadership at some level. It’s not a stretch to believe Jonathan would have been heavily pressured by Young himself to live the principle of polygamy shortly after the credits roll.

Shoutout to my fourth great-grandmother Sarah Brown who at age 19 married Wilford Woodruff, age 46, becoming his fifth wife.

Linda Darnell’s righteous indignation is a key ingredient to the scene that wouldn’t quite work without it. Zina sees polygamy from an outsider’s perspective that most of the audience of the time, and today, would hold. Sadly the film is all too accurate to real history. Jonathan and the men never take the concerns and desires of the women involved with any level of seriousness.

Given that in the eighty-plus years since Brigham Young, modern films rarely tackle Mormon polygamy in a straight, dramatic manner, it’s absolutely breathtaking to find such blatant criticism of Latter-day Saint polygamy coming from a woman in a classic film. Even Latter-day Saint-helmed productions—with 2018’s film-directed independent film Jane & Emma starring Danielle Deadwyler being the rare exception— treat polygamy simply as a harmless joke.

Darnell can claim something few modern actors and none of her contemporaries can: playing—if only briefly—the voice of the many forgotten women of Mormon history.

Moroni Olsen (left), the only Mormon in the cast, plays the small part of Doc Richards.

The Next Mormon Epic?

I don’t expect Brigham Young, constrained by the Production Code and mid-20th century American culture still hesitant to criticize religious institutions, to be the definitive portrayal of Mormon history. Instead, I think it’s a fascinating artifact of not only Mormons’ place in 19th-century popular culture but also Hollywood’s relationship to adapting historical events.

Every time I revisit the film, I appreciate the filmmakers were willing to stick their necks out, go against the grain from previous Mormon portrayals, and cover such a fascinating and near-to-me part of American history. Compared to the Latter-day Saint church’s depictions of these events that rarely acknowledge polygamy ever happened, Brigham Young at least succeeds in depicting Mormon events without the white-washed, evangelical slant that many Latter-day Saint filmmakers have fallen into.

I would still love a hard-hitting movie or HBO series covering both the inspirational and deeply troubling stories of Mormon history. Obviously, it’s a pretty big part of my identity and past but I think the history of Mormonism holds key truths about the identity of America as a whole and is ripe for rediscovery by a larger, more mature American audience.

And plus, my family says my chinline mirrors my fourth great-grandfather’s Wilford Woodruff if Hollywood ever wants to cast me in the role! Until that happens though, I’ll still have the historical oddity of Brigham Young to have very strong opinions about.

My post on Brigham Young (1940) is a part of Musings of a Classic Film Addict‘s Linda Darnell Blogathon celebrating the career of the gifted actress on what would have been her 100th birthday. Visit the main blogathon post to read other great articles diving into Darnell’s career and films.

Really enjoyed this interesting, informative, and epic post, Shawn! I’m sure I’ve heard of this movie before (I think), but I’ve definitely never seen it. I’m not sure, after reading your take on it, whether I’ll be seeking it out, but if I stumble upon it, I might just give it a try. Thanks for the introduction!

— Karen

Thanks! It definitely is a movie unlike any other classic Hollywood film I can think of.

This is an incredibly well-informed article that gave me so much insight to a film I’ve seen but mostly forgotten. I agree though that Dean Jagger didn’t seem to be quite the leader that the real Brigham Young was and the “glossing over” of the distasteful parts of his life definitely suited the screen. I envy the readers who get to read your piece and then compare to the film! Thank you so much for participating in the blogathon and honoring Linda for her centennial!

Thanks so much for putting the blogathon all together! It’s been great to read through a lot of them while catching up with the films of hers I haven’t seen.

Wow, this is so interesting! I saw the film on TCM years ago but this really makes it make sense.