Outside of film enthusiasts, film gauges aren’t thought about much. In a digital world where the majority of the public under forty have never touched a reel of film, people don’t even know what film gauges are. 35mm, 16mm, and 8mm are just arbitrary measurements instead of compelling stories of technological change and evolution. Celebrating its centennial this year, 16mm might be the most revolutionary film gauge that drastically altered how the industry and the public engaged with movies.

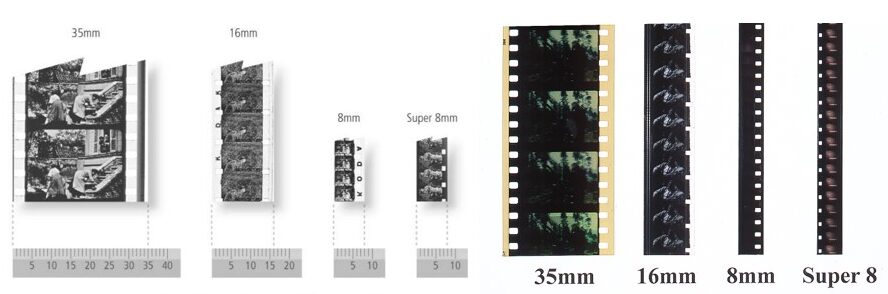

The four most common film gauges: 35mm, 16mm, 8mm, and Super 8.

Film Gauges and the Birth of 35mm

Film gauges describe the width of celluloid film in millimeters. Inventors in the 1880s and 1890s experimented with early moving pictures using film made from different materials and in various sizes. As a nascent film industry sprung up in the late 1890s and early 1900s, setting a standardized size and type of film quickly became crucial for the future of the medium. While a plethora of film formats worked when most filmmakers showed their films on their own equipment in the early days of motion pictures, a reliable international market would need standardized film formats in order to succeed.

35mm, first created in 1889 by Edison’s partner W.K. Dickson by cutting Eastman’s 70mm raw film in half, quickly became the dominant film gauge by the turn of the 20th century. (Edison tried unsuccessfully to claim exclusive patent rights to the 35mm format before a judge ruled against him in 1902.) It took several more years for the industry to settle upon standardized image size and perforations—sprocket holes on the sides of the image that the projector uses to advance the film—for 35m film.

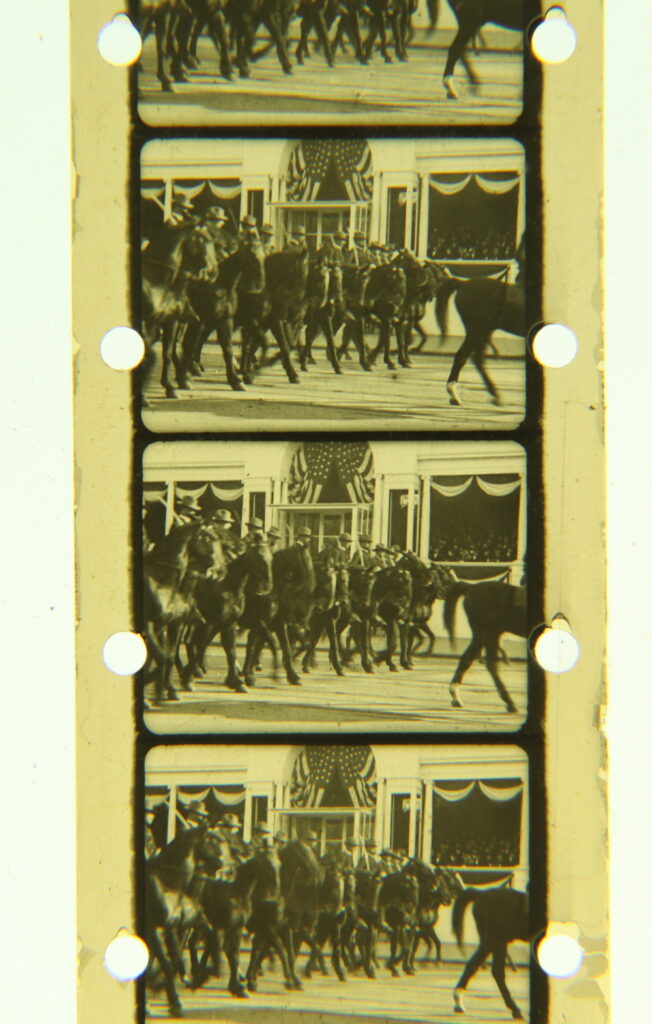

(Left) 1890s Edison 35mm film with four rectangular perforations per image. (Right) 1890s Lumiere 35mm film with one circular perforation per image.

Edison’s aggressive enforcement of his motion picture patents and monopolist business practices might have initially been a major driving force in the standardization of 35mm film but the format also has several positive qualities that fit well for both film production and distribution.

The image remained large enough to view unspooled yet not small enough that the film reels were not too heavy for simple handling or transportation. The perforations, one set punched on each edge of the film, took up only a few millimeters allowing for the projected image with plenty of size and quality to screen for large audiences. Even today 35mm remains the most well-suited film gauge for theatrical distribution.

16mm Film Bursts on the Scene

If 35mm film is the story of standardization, then 16mm is all about accessibility. Before the widescreen explosion of the 1950s, filmmakers and exhibitionists happily stuck with 35mm as the sole film gauge for theatrical distribution; however, enterprising companies quickly saw an opportunity to create a home video market by creating smaller, amateur-friendly film gauges.

Pathe Freres, attempting to add a revenue stream independent of theaters, released 28mm film in 1912. Made with a safety film stock much less flammable than the standard nitrate allowed amateurs to screen films in their homes with no personal danger. The format made some success in Europe upon its release but after World War I gradually lost business to more affordable competing film gauges. In 1922, Pathe would again release a new format 9.5mm film that would prove popular in Europe but never take off in America.

Ads for 16mm cameras and projectors featured in a 1924 issue of the Motion Picture Photography for Amateurs Magazine.

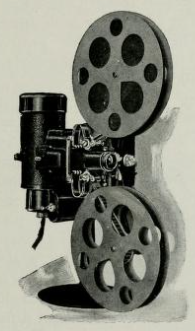

Instead, Eastman Kodak’s 16mm film would become the most important small-film gauge in America and eventually around the world. In 1923, the Eastman Kodak Company released their 16mm camera called the Cine-Kodak alongside a 16mm projector the Kodascope. A major marketing push emphasized both the affordable prices and the ease of using the new 16mm format. Not only could you easily record by just pressing a button, Kodak customers sent their film to the Eastman laboratories where technicians developed the film and shipped it back to the Cine-Kodak user.

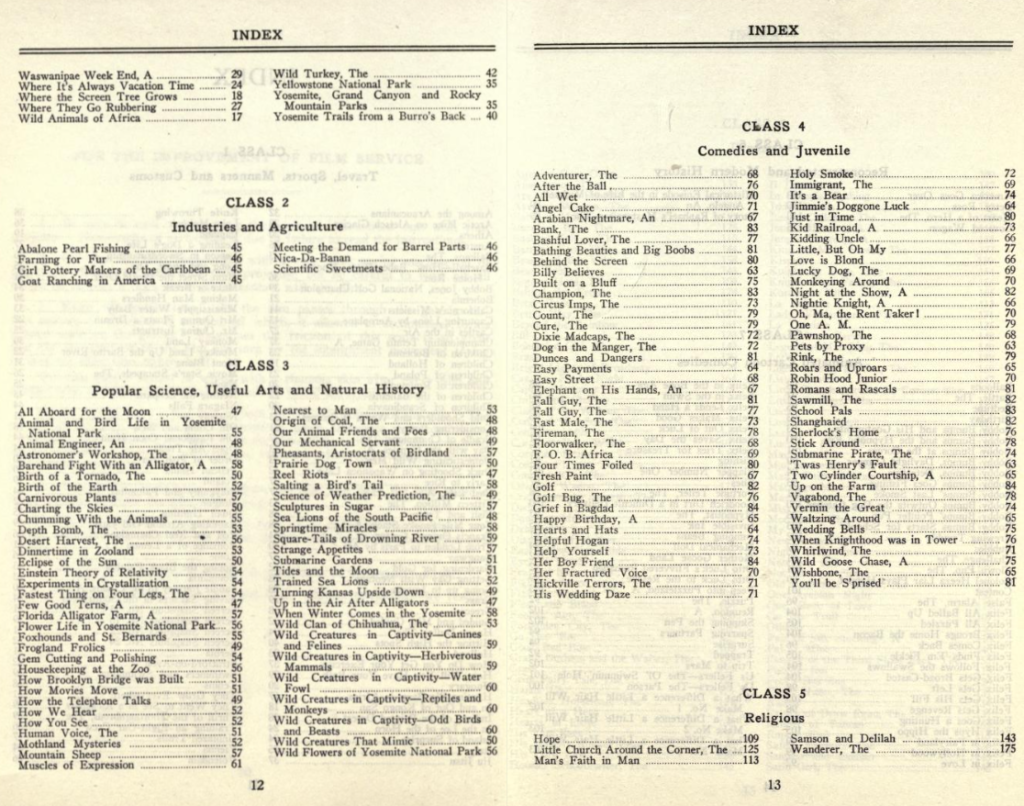

Renting Hollywood movies for your new 16mm projector was just as easy as shooting and developing your home movies. Using their close relationship with Hollywood, Eastman Kodak built up a collection of thousands of films on 16mm to offer for rentals of popular films they named the Kodascope library. Through a subscription service, customers would receive Kodascaope catalogs they could use to order films through the mail. While many of the films were abridged to fit more neatly on fewer reels, it still beat not seeing the film ever again!

(Left) Kodascope mail-in order (Right) Kodascope 1925 Catalog

Costing nearly $6,000 in 2023 for the 16mm camera, projector, tripod, screen, and splicer, only upper-class families could afford 16mm equipment when first released in 1923. Even with the high barrier of entry, 16mm’s success signaled the public’s interest in not only easy-to-use filming equipment but also the ability to watch their favorite films long after their initial first run at their local theater.

Luckily for the eager public, Kodak and its competitors worked towards making a cheaper product with large dollar signs in their eyes. The future of the medium would depend on expanding the accessibility of the medium from the rich to the everyday middle-class American.

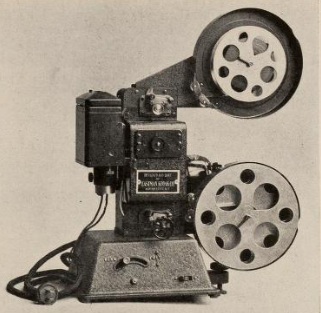

The top 16mm projectors circa 1925: (Left) Bell and Howell (Top Right) Cine Camera (Bottom Right) Kodascope.

The Many Lives of 16mm Film

Initially marketed solely to those interested in shooting and screening films at home for personal use, 16mm slowly grew into a multi-faceted tool for various purposes. The early 1930s saw the addition of optical soundtracks and reliable 16mm cameras and projectors that could record and amplify sound. The Kodachrome, the first widely accessible color photography, was released in 1935.

Because of these new features and the gradually decreasing costs of equipment and film, 16mm became the preferred format for non-theatrical exhibitions. During World War II, the military especially invested in the medium to screen educational and instructional films in military training and to the civilian public. For decades, school libraries held 16mm films for classroom use before the rise of video.

With the release of the more compact and cheaper Super 8 mm in 1965, 16mm slowly lost its position as the preferred film for the home video market. Super 8’s ascension did not prove 16mm’s death knell, however; the 1950s and 1960s saw television and independent film producers latch onto 16mm film. More affordable and portable than 35 mm but with a higher picture quality than Super 8, 16mm straddled the line between the professional and accessible.

John Cassevetes’ Shadows set off a wave of 16mm independent films in the ensuing decades.

For instance, television producers around the world used the 16mm format to shoot their shows. Even after the rise of digital, shows like Scrubs, The Walking Dead, and The Big Bang Theory continued shooting on 16mm despite the increased expense of shooting film with four cameras.

Perhaps the most influential avenue of 16mm production was the independent film. Starting in the late ’50s, filmmakers like John Cassavetes shot low-budget, critically acclaimed films such as Shadows (1959) on 16mm that would inspire a whole new generation of filmmakers. Later, the 1990s saw an influx of cult classics shot on 16mm from Kevin Smith’s Clerks to Peter Jackson’s zombie flick Braindead. The accessibility the 16mm format provided to amateur and low-budget filmmakers not only lowered one major obstacle for aspiring creators but also drastically altered the desired look of even the biggest budget film to a more realistic gritty environment.

What is the Next Century Looking Like for 16mm film?

Just as 16mm fell behind Super 8 in the home market, the format would suffer the same fate with the rise of video and later digital cameras. We might be a couple of generations removed from the golden days of 16mm film but the format has found its small niche in the film industry.

Big-name filmmakers still use 16mm for various uses today. Some shoot on 16mm to recapture a time-specific look, such as the Vietnam War flashback scenes in Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods. Others still use the format to save on production costs such as Kathryn Bigelow on the Best Picture-winning The Hurt Locker, allowing her to shoot with many more cameras and expose much more film than if she had used 35 mm film. Other acclaimed directors from Darren Aronovsky to Wes Anderson champion the format returning to it on multiple projects.

Manhandled (1924) only survives because of an abridged 16mm at-home print.

In the field of film preservation, 16mm is the gift that keeps on giving. According to a 2013 Library of Congress report on the survival rate of American silent films, there are “365 and 432 American silent feature films that survive only in 16mm”. While the studios might have junked their 35 mm prints of these films, personal collectors held onto their 16mm versions for us decades later to view and enjoy. Several notable films only survive their 16mm abridged, show-at-home versions including films from acclaimed directors like William Wyler, Clarence Brown, and Eric von Stroheim.

So while you might not find much 16mm film out in the wild today, you will still find its impact and influence in nearly every aspect of our modern media landscape. Here’s to another hundred years of 16mm!

Going through my families estate I have come across about 15 reels of 16 mm silent films still in original Kodascope library inc cases. I believe the projector is in a box as well. I’m still in the process of going through boxes. After reading your article, I believe it should not be sitting in a box. Any thoughts on who may be interested in purchasing these items?

Very cool find! Probably the best place for them would be to try and see if any collectors would like them, either to buy or just for free depending on their condition and what you want. You could put them up on EBay or on communities that trade film like this exchange thread on Nitrateville.

Would love you hear what titles and from what year these Kodascope films are from!