Whether in a close-up of the glamorous Marlene Dietrich or an alluring wide shot of the Morrocan desert, Von Sternberg’s ability to create a visually stunning image stands unmatched in the annals of film history. Josef von Sternberg might be known for his string of 1930s successes but his films stretch from the height of the silent era to the beginning of widespread independent film production in the 1950s.

So consistent are Von Sternberg’s narratives themes and visual style that you often can identify a Von Sternberg film, like many auteurs, from a small clip. Looking at both his small independent film screen debut The Salvation Hunters and his a final personal project made far away from the antagonistic studio system Anatahan perfectly encapsulates Von Sternberg’s many strengths, passions, and quirks.

Screen Debut: The Salvation Hunters (1925)

After working as an assistant director on several films in the early 1920s, Sternburg sought to become a director in his own right. Along with actor George K. Arthur, Sternburg largely self-financed The Salvation Hunters for roughly $5,000—nearly the equivalent of $100,000 in today’s money.

Salvation Hunters leans into its low budget without looking amateurish. Shoot on dirty city streets and garbage-filled docks, the poverty and despair of the main characters feel palpable and realistic. Especially in the film’s opening scenes, Von Sternberg shows off his penchant for turning the everyday into the glamourous creating vivid visuals with a dirty, grimy dock and rundown buildings. Even from his first picture, the man knew how to frame a shot for maximum effect.

Two striking compositions from The Salvation Hunters in everyday locations.

Although the majority of the actors were extras or bit players before making the film, they never seem out of place or unnatural. Of course, the film doesn’t ask them to do much as Sternberg’s camera seems content merely observing them as they mope about and look off into the distance. Plenty of low-budget films fumble the acting so even getting adequate performances in such a small movie is nothing to stick your nose up at.

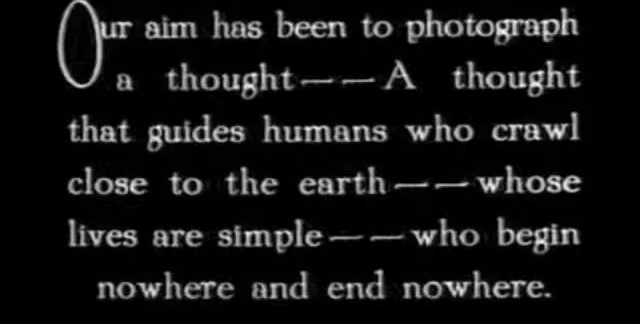

While the photography and production values foreshadow Von Sternberg’s rise as a formidable auteur, the plot and themes of Salvation Hunters make the film feel like a student film. The pretentious opening title cards, declaring that the film attempts to photograph a thought, set the film up to be some deep thought experiment that it fails to reach. Characters remain distant, more otherworldly and glamorous than real and relatable. The plot meanders as Von Sternberg focuses more on creating alluring visuals rather than crafting a compelling story with griping narrative tension.

That’s deep…I guess?

The film follows a young couple and an abused boy who leave their squalor small town environment for the slums of the big city hoping to make a life for themselves. Of course they are immediately taken advantage of and find that the big city holds the same challenges and limited economic opportunities that stifled them back home. The main story arc is the man overcoming his cowardness and gaining the courage to fight for his and his wife’s dignity and future. We end the mostly dour film with a little a bit of hope for the characters even it may be largely unearned. Like I said, not much of a plot. You might even just call it a thought!

During its initial run in New York, The Salvation Hunters flopped hard ultimately failing to last a week on screens. Due to Arthur’s persistence and his connections in Hollywood a print of the film landed up in Charlie Chaplin’s home and screened for a private audience including United Artists’ creatives Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and Joseph Schenck. Lucky for Von Sternberg, the privileged audience enjoyed it—Chaplin especially—who ended up distributing it through United Artists after much fanfare.

The cast of The Salvation Hunters.

Although some of the Coastal critics shared Chaplin’s enthusiasm for the film and recognized Von Sternberg’s rising star, the film failed to win over most audiences. Upon its wider release, Variety absolutely panned the film:

Word came a month or so ago from the west that “The Salvation Hunters” was the work of a new cinema genius, that it was a revolutionary picture, that its theme was original and the treatment masterful. On top of that Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford endorsed it as being the ultra-ultra in picture production.

Applesause.

“The Salvation Hunters” is nothing more nor less than another short cast picture to express an apparently Teutonic theory of fatalism. The derelicts of the world are the characters and a flock of freshman philosophy the theme.

Variety Feb 4, 1925

Ouch. Luckily for Sternberg’s career and image, Hollywood studios and not Variety were in charge of deciding his future. After a brief unsuccessful stint at MGM, who quickly signed Von Sternberg to a contract following The Salvation Hunters, Sternberg solidified himself as one of the most gifted directors at Paramount in the late 1920s with hits like the great gangster film Underworld.

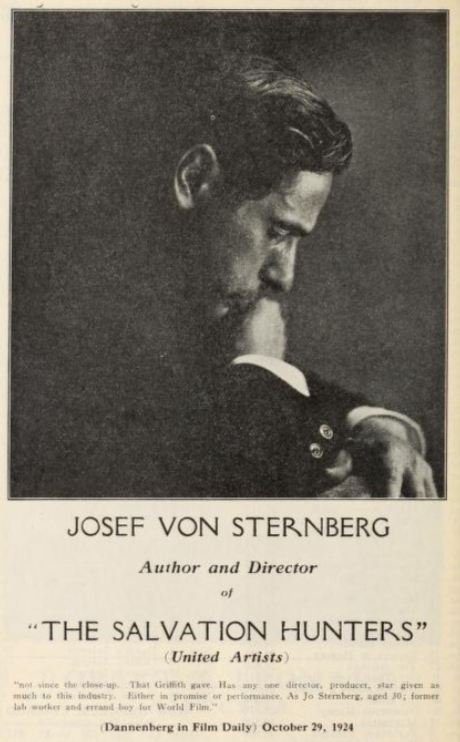

In The Salvation Hunters‘ limited publicity, Josef von Sternberg took center stage as the next big thing.

The Last Hurrah: Anatahan (1953)

After his most successful near-decade run at Paramount came to a close in the mid-1930s, Sternberg bounced around several studios always trying to increase his creative control. To gain near complete control over a film’s direction, script, and cinematography as he had for The Salvation Hunters, Von Sternberg traveled to Japan to make his final film Anatahan.

Anatahan tells the true story of a group of Japanese soldiers stranded on the remote island of Anatahan in the Pacific Ocean during and after World War II. A Lord of the Flies type tale, the survivors slowly lose control and begin fighting over the only woman on the island during their seven-year-long isolation. Although based on a memoir from one of the survivors, Von Sternberg injects the narrative with plenty of narrative flourishes and emphasizes themes that particularly interested him throughout his career.

The Japanese survivors on the small, remote Pacific island Anatahan.

The entire film is spoken in Japanese without any English subtitles. Instead, Von Sternberg himself narrates translating the spoken Japanese when necessary but largely sticking to explaining the events onscreen or detailing the motivations or emotions of the characters. Such a narrative approach might have been an opportunity for Von Sternberg to pull back into his silent film toolkit and tell his story visually. Unfortunately, his monotone narration becomes a crutch that limits the potential of the film.

The jungle sets look quite convincing, made on a sound stage in Kyoto. Like always, Von Sternberg’s camerawork is top-notch keeping his camera constantly moving the jungle landscape. For the majority of the film, Von Sternberg aims for realism restraining from using his trademark expressionistic lighting.

Josef von Sternberg goes out with expressive lighting in his final scene as a director.

Much of the film might not match Von Sternberg’s previous lightning and cinematography of previous outings but the finale does not disappoint. As the survivors return home to Japan, he leaves us with one final stroke of lighting mastery. As one character imagines the dead among their group returning home after their rescue, the dead start as dark silhouettes against a blurry background. The dead move forward into a static light source that slowly illuminates their face bringing them into focus. It’s simple yet effective conveying the lingering effects of the whole experience on the survivors moving forward.

It wouldn’t be hard to see an Anatahan made in Hollywood that heightened the realism and played based on a true story factor. Von Sternberg instead is interested in exploring the human condition and creating a universal category. He is not worried whether he accurately retells the events of the Anatahan survivors but instead seeks to explore natural man’s inner desires.

Male Gaze: The Movie

Much like The Salvation Hunters, Anatahan received rave reviews from a select group of creatives but fared poorly amongst wider audiences. Many Japanese critics took issue with Von Sternberg’s emphasis on general human nature over the particulars of the true story, arguing that such an approach exoticized the films’ characters.

American audiences, whom the film was targeted for with its English narration, similarly felt cold to the film possibly due to either the subject matter reminding them of the war or the more artistic slant. In his review for the Evening Post, critic Patrick Fleet dismissed Anatahan as a film for those only interested in art cinema because “the treatment is generally heavy-handed and at times tedious”.

Von Sternberg never meant for Anatahan to be his final film as he actively tried to get multiple projects off the ground over the next decade. He continued to use his talent as a visual storyteller in his paintings. Even if he never completed another project, Von Sternberg stayed in the film community teaching film classes at UCLA.

The First and Last of Josef von Sternberg

Salvation Hunters and Anatahan might not be among Von Sternberg’s best films but they perfectly reflect Von Sternberg’s masterful use of lighting and his allegorical approach to exploring human behavior in the face of extreme moral and physical obstacles. Both feature a group of misfits thrown together by life’s constant abuse—poverty in one war in the second. Von Sternberg aims to explore if not to answer how humans respond to

Josef von Sternberg has always been a director I admire much more than I love. As seen in both these films, the questions he asks are interesting but I find his method a little offputting. I find it hard to relate myself to the characters as his films typically remain distant from them. In painting these characters as allegorical stand-ins for everyday people, Von Sternberg’s characters often lose the small details and idiosyncracies that make audiences love and relate to characters.

My favorite Josef von Sternberg films are his late silent films which I feel do the best balancing Von Sternberg’s visual storytelling with compelling characters and plots. Underworld is a wonderful, fast-paced gangster film that marries Von Sternberg’s impeccable lighting and mise en scene with Ben Hecht’s snappy script. Docks of New York succeeds in capturing poverty in many places The Salvation Hunters failed and might be Von Sternberg’s most beautiful film which is saying a lot with the amount of talent he had.

Even when I don’t love a Von Sternberg film like The Salvation Hunters or Anatahan, I always come away more confident in calling him the most talented and innovative visual classic Hollywood director. I’ll keep watching his films largely because of my fascination with his talent in framing and lighting his actors in novel ways that often ran counter to the traditional Hollywood editing style of the studios at the time.

This post is a part of the Classic Movie Blog Association Blogathon SCREEN DEBUTS & LAST HURRAHS exploring the first and last films of performers and filmmakers. Visit the blogathon’s main page for more great in-depth analyses and discussions.

Great Post. The Salvation Hunters came to my attention due to my interest in (ok, obsession with) Chaplin because of Georgia Hale. And what wouldn’t we pay to see “The Sea Gull: A Woman of the Sea”? I agree with your admiring more than loving assessment. There is no denying he was a singular artist and made some darn good looking films.

Thanks! It’s really interesting that Chaplin took to the film so much and cast Georgia Hale after seeing it but I guess giving his own upbringing in poverty it makes sense he’d connect to it.

And that one picture of Edna Purviance in fish nets from The Sea Gull looks fascinating. I wonder just how experimental The Sea Gulls would have turned out with a young Von Sternberg.

Wow. This is fantastic and I enjoyed it thoroughly. You make a great case as to why he should be considered one of the greatest ever.

Aurora

Thank you. I know while writing it I felt really tempted to get the three disc set of his late silent films from Criterion. I definitely feel like I need to give Docks of New York a rewatch.

I have not seen The Salvation Hunters or Anatahan, but have seen Von Sternberg’s more celebrated silents and later sound films. I have great admiration for his work and do sometimes love it. His visuals are, for me, irresistible. And, of course, what he did with and for Dietrich is epic. I believe it was among extras for the I, Claudius series boxed set that I saw the remaining footage of his aborted 1937 film version of that book. Definitely worth seeing. And I believe the extras also included a film clip of Von Sternberg discussing/teaching lighting on a small set. As I understand it, Von his last released film was Jet Pilot in 1957. It had apparently been completed many years earlier (and prior to Anatahan) but was held up forever by producer Howard Hughes. All that said, I enjoyed your review of his first and last films very muchy and thank you for giving one of film’s early masters his much-deserved due in this blogathon.

Thanks! I had no idea Von Sternberg had started working on an adaptation of I, Claudius. Charles Laughton really is the perfect fit for the material and now I am curious to watch the remaining footage of the ditched project.

I largely feel the same way about Von Sternberg as you do, where I appreciate his work more than love it. (My favorite of his films is either The Last Command or The Scarlet Empress, for what it’s worth.) Both his first and last films sound interesting in their own rights– strange how both were seen as too “arty” for general audiences!

Thanks for sharing this career First and Last with us. It was surprising to learn his career started in the mid-1920s, but not surprising to learn his talent was already evident.