Legends become so enmeshed in the cultural consciousness that they appear in numerous forms and adaptations centuries after their initial creation. The German folktale Faust is one such tale, inspiring dozens of books, plays, operas, and films since its first iteration in 16th-century German literature. In the tale, the scholar Faust sells his soul to the devil for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. While various versions differ on what Faust does with his newfound demonic power, the story ends with either Faust’s eternal damnation, paying the price for his short earthly excess, or his redemption, traditionally through divine intervention and the grace of the virgin Mary or another virtuous female character.

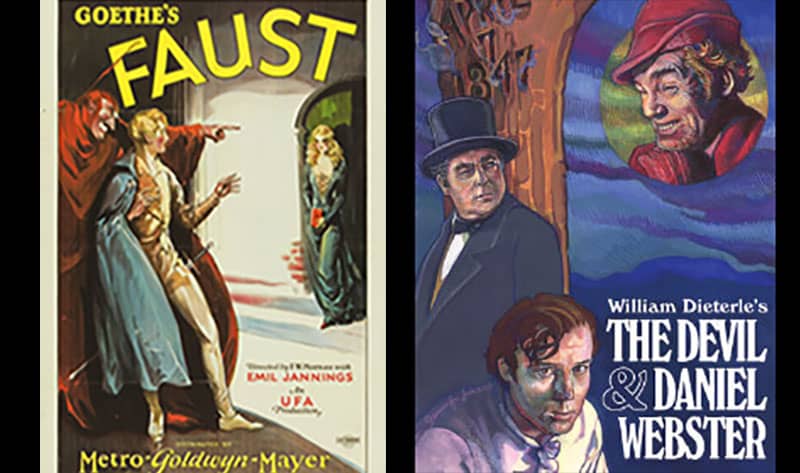

Just as the Faustian legend has been ripe for literary adaptations for five centuries, Faust has been the inspiration for numerous screen classics. Both F.W. Murnau’s 1926 Faust and William Dieterle’s 1941 The Devil and Daniel Webster (also known as All That Money Can Buy) adapt the tale of Faust to great success in their own unique way. While Murnau’s adaptation uses Christian imagery and mythology in his medieval tale to explore humanity’s good and evil nature, Dieterle’s film transplants the Faustian legend to 19th-century America to explore the American soul. Both films’ unique interpretations and high artistic quality stand as a testament to the universality and longevity of the Faustian legend.

This review is part of The 2021 Classic Literature On Film Blogathon hosted by Silver Screen Classics. You can read the rest of the blogathon’s wonderful lineup at the blogathon’s main page.

Faust (1926): Murnau’s German Masterpiece

Murnau’s Faust was his last film in Germany before he moved to Hollywood. One of the most skillful and well-known German Expressionist filmmakers, Murnau spares no expense in bringing his vision of Faust to the screen, creating visionary special effects, haunting Biblical imagery and beautiful cinematography rarely matched in cinema. The film itself takes much of its story from German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1808 tragic play Faust, centering Faust at the center of a battle between the devil and God.

Murnau begins Faust on a cosmic scale, opening with the demon Mephisto (played by Emil Jannings) flying with the Four Horseman of the Apocalypse through the sky to claim dominion over the Earth. An angel appears to protect humanity and defend their inherent good and desire for truth. Mephisto, espousing his doubt in mankind’s goodness, senses an opportunity. He makes a bet with the angel: if he can wrest away Faust’s soul, the most pious man on Earth, from God, the devil gets to rule over humanity and the Earth.

Mephisto spreads the plague across Faust’s village.

Once the eternal stakes of the film have been set, Murnau focuses on Faust’s struggle to help those suffering in his medieval town from the plague personally sent from Mephisto. After his scientific knowledge and prayers to God have failed him and his town, an elderly Faust (played by Gösta Ekman in heavy makeup) burns his alchemy books and Bible in despair. As his books burn, he is enticed by a page that outlines how to call upon the devil and gain his immense power. Hoping to save his town from the plague, Faust calls upon the devil and enters into a pact to have his power for one day, essentially a 24-hour free trial.

Faust’s altruistic motive for signing his soul over to the demon Mephisto is of utmost importance to the narrative. Faust only submits himself to the devil because God and his worldly knowledge have failed him, proving his selfless desires to help others and gain more pertinent wisdom. While the film doesn’t go as far as to suggest that Faust’s deal with the devil is a pious act of faith, it does help justify why a highly esteemed man of God would fall in with the devil.

Denouncing God and His heavenly hosts to gain the devil’s power and glory, Faust immediately goes about miraculously healing the sick in his city; however, the people discover the source of Faust’s newfound demonic healing power and attempt to stone him. Having failed to help his townsfolk with his demonic powers, Faust is stuck between a rock and a hard place. He has no use for the devil’s power but cannot turn towards God, let alone be in the same room as a cross. A despondent Faust tries to kill himself by drinking poison but Mephisto prevents him from doing so. In Faust’s moment of despair and regret, the demon offers to make him young again, an offer Faust willingly accepts. While Faust’s initial agreement with the devil took him down a dangerous path, his decision to use this power for his own selfish desire is the first sign that Faust is in for far more than he initially bargained for.

Faust uses his demonic powers to heal the sick.

With his newfound youth, Faust forgets about his plague-infested town and takes up Mephisto’s offer to spend a night with the most beautiful woman in all of Italy. He’s got a few more hours in his twenty-hour trial so he might as well use it for something. Just before Faust is about to spend the night with an Italian princess, Mephisto appears to notify him that his time has run out. Faust, in the heat of the moment, willingly makes his pact with the devil permanent to continue his night of lovemaking. This is Faust’s point of no return, trading in his eternal soul for fleeting youth, money, sex, and power. Faust is now free to forego his faith and altruism in favor of his own personal desires. Any good that Faust had exhibited prior to this point is lost in a hasty deal with the devil.

After spending some time living according to his own selfish desires, Faust becomes unsatisfied and yearns to return to his home. While the narrative up to this point in the film is typical of most Faust adaptations, Murnau includes a young maiden in the story named Gretchen that was first introduced by Goethe. Faust meets Gretchen, a young churchgoing maiden (played by Camillia Horn), at a large Easter celebration when he returns to his hometown. Mephisto who disapproves of her quips to Faust: “I know more obliging wenches for you here!”.

Even if Faust has indulged in orgies and various other frowned-upon activities, he has never been fully satisfied with his newfound lifestyle and youth. Gretchen provides redemption for Faust. Instead of simply seeking to fulfill his carnal desires, Gretchen’s devotion to the church and her humble, lower-class status shows us that Faust has managed to keep some desire for good.

Mephisto looking to cause trouble outside of Gretchen’s humble abode.

Murnau spends several minutes on Faust’s courtship of Gretchen, a major contrast to Faust’s previous escapades with women and his time spent with the devil. The couple chase each other around a flowering spring garden and kiss each other under a tree, much more chaste behavior compared to Faust’s one-night stand with the princess. While Faust had been unsatisfied with the empty life the devil had given him, Faust finds in Gretchen the joy and innocence he had given up when he entered the pact with the devil.

Mephisto clearly understands what Gretchen’s relationship with Faust represents and will do everything in his power to stop the two of them from spending time together. When Faust sneaks into Gretchen’s house late at night, Mephisto notifies Gretchen’s brother that her sister is about to sleep with another man, resulting in a stand-off between him and Faust. After Mephisto stabs Gretchen’s brother in the back when he is fighting Faust, the demon screams throughout the town that Faust has murdered his lover’s brother. Faust then runs away, leaving Gretchen to face the consequences of bearing and raising their child born out of wedlock in her highly judgemental and religious town.

Gretchen calls out for Faust’s help after he has run away.

Abandonded by Faust and shunned by her community, Gretchen roams the streets with her baby. After accidentally killing her baby in a snowstorm, Gretchen is sentenced to death and calls out to Faust for help. Faust, brooding and bored with his demonic lifestyle, demands that Mephisto take him to stake to save Gretchen. Seeing the devastation his selfish desire for youth has brought upon his innocent love, Faust renounces his pact with the devil and throws himself on the stake alongside Gretchen. The film ends as Gretchen’s and Faust’s spirits are received into heaven. The devil loses the bet and is sent back to hell when the angel from the film’s opening declares that Gretchen’s love has returned Faust’s soul to God.

The film is split into two very different halves, the first detailing Faust path to the devil’s servitude and the second building his and Gretchen’s relationship. We only briefly see how Faust spends his time with the devil leaving us to fill in the gaps (probably a lot of orgies I am guessing). Many literary versions of the Faust tale include numerous escapades Faust undertakes with his demonic powers; however, by slimming down the narrative to Faust’s descent into wickedness and his eventual redemption, Murnau focuses in on the battle between good versus evil.

Faust throws himself onto the burning stake with Gretchen.

Mephisto’s success in quickly turning one of the Earth’s most righteous men into a selfish servant of the devil is a cautionary tale that each of us has the potential to do a lot of good or to do evil. Faust’s fatal flaw wasn’t teaming up with the devil after God and science had failed him but in forgetting his love for others when he uses the devil’s power to pursue his own carnal desires. The remedy for the devil’s influence in Murnau’s tale is love: the love of God and of our fellow man. Gretchen’s redeeming love and influence on Faust echoes the virgin mother’s redeeming power in Catholicism and medieval European Christian theology, giving added depth to Murnau’s Biblical imagery. Just as Faust’s love for Gretchen and his willingness to give up his youth and personal pleasure for her sake redeems Faust’s eternal soul, Murnau’s Faust proposes that all humans can be saved through love.

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941): Faust and the American Dream

William Dieterle, while not as well-known of a director as Murnau, directed and acted in his native Germany in the 1920s before emigrating to Hollywood in 1930. Interestingly enough, he played a small part in Murnau’s Faust as Gretchen’s brother. When he directed his own Faustian tale at RKO in 1941, Dieterle took a very different route, adapting not Goethe’s version of the Faustian tale but Stephen Vincent Benét’s Americanized short story. Benét’s short story and Dieterle’s The Devil and Daniel Webster drastically change the setting of the story, the central protagonist’s motivations, and his path to redemption.

Dieterle’s different tone is apparent in the opening frame. While Murnau couched his Faust tale in a cosmic battle between the devil and God, Dieterle’s Faustian tale opens with a title card reminding the audience that the following story of a humble 19th century New Hampshire family “could happen anytime—anywhere—to anybody… it could even happen to you”.

In The Devil and Daniel Webster, we are not in the domain of eternal gods and devils but in an idealistic, rural America long since in the past. Jabez Stone, our American Faust, is the ideal agrarian of Jeffersonian democracy and early America, a young hard-working farmer surrounded by his pious family and the word of God. Jabez is not a fountain of knowledge and wisdom like Murnau’s Faust but an everyday individual who gets frustrated when things don’t go his way saysing ‘consarn it all’ much more than his patronly mother would like.

Mr. Scratch pays Jabez Stone a visit.

After a streak of bad luck and a series of mishaps, Jabez Stone (played by James Craig) accidentally summons the devil in a fit of rage while working on his farm. The devil, who refers to himself as Mr. Scratch (played wonderfully by Walter Huston), offers Jabez a pile of Hessian gold and seven years of prosperity and ‘good luck’ in exchange for his soul. For Jabez, his hard work on the farm has not been able to provide his family with everything they want, need, and in his opinion deserve. Accepting Mr. Scratch’s offer is much less about cutting corners and more about reaping the rewards of his hard work and devotion to God and his family which have continually been delayed because of his bad luck. With Mr. Scratch’s gold, Jabez initially uses his wealth to pay off his family debts, buy his wife a new bonnet, and gain favor with his local townspeople.

Jabez isn’t the only one who is well acquainted with Mr. Scratch. Miser Stevens, who ruthlessly exploits the town’s out-of-luck farmers, is a long-time business associate with Mr. Scratch. When the famed New England congressman Daniel Webster (played by Edward Arnold) passes through town, we find out that even he is acquainted with Mr. Scratch who has long sought to gain his soul in exchange for making the aspiring Webster the next president of the United States.

Webster, however, has declined the devil’s offers, instead advocating for legislation that would help poor farmers like Jabez. Jabez strikes up a friendship with Mr. Webster and gives a speech on behalf of Daniel, giving him prestige amongst his fellow farmers. Jabez practices what he preaches as well, generously giving his wealth to his farmer friends in need after a hailstorm destroys everyone’s crop but his.

After fulfilling his initial wishes to better provide for his family, Jabez’s conscience nags him. He only made the pact with the devil to finally give his family everything he thought they deserved. Now that his family and friends are taken care of, what could he possibly use the devil for? When he tries to get out of his deal with the devil, Mr. Stratch appears to remind him that there is nothing he can do to release himself from his word. Jabez has all that money can buy until Mr. Scratch will collect his soul on Apri 7, 1847 as per their contract. Jabez, with no way out of his pact and no other ways to righteously spend his money, slowly renounces Webster’s ideals of helping the poor and advocating for local farmers’ needs and begins to succumb to the devil’s temptations to indulge in his own selfishness and greed.

Jabez fails to break his contract with the devil.

Over the next seven years, Jabez becomes the richest man in New Hampshire, largely due to his ruthless business practices that take advantage of his former farmer peers. He neglects his wife, mother, and young child. Instead, Jabez spends the majority of his time with the family’s new maid (played by Simone Simon) in his newly built mansion. Jabez has lost his hard work ethic and religious piety, playing poker and taking long rides on the Sabbath instead of attending church. Jabez has turned into an enemy of the townsfolk, holding burdensome loans over most of his former farmer friends.

The most significant change in this American Faustian tale is how Jabez is redeemed. After years of self-indulgence, Jabez’s conscience returns after he witnesses Mr. Scratch collect Miser Steven’s soul at the end of his contract. Daniel Webster, the symbol of the American values that Jabez once espoused, comes to Jabez’s mansion to denounce his behavior and moral ineptitude. Called out by Daniel and his family, Jabez finally realizes the error of his ways and fears for his eternal doom just as his seven-year pact is about to end. At the eleventh hour, Jabez rushes to Daniel Webster’s side to beg for forgiveness and his help to stop the devil from claiming his soul for eternity.

At the behest of Daniel Webster, Mr. Scratch agrees to conduct a trial by jury over Jabez’s soul, his right as an American. Jabez’s chance at redemption does not come from love or adherence to God but from the American Constitution. Mr. Scratch summons a judge and jury of some of America’s most notorious criminals and traitors, from Edward Arnold to Judge Hawthorne of the Salem witch trials, all of whom made deals in their previous life with the devil for power and wealth just like Jabez. All seems lost in this rigged trial as Mr. Scratch’s prosecution rests his case on the unbreakable contract between himself and Jabez Stone. Despite the almost insurmountable odds, Daniel Webster puts his own soul on the line to make a heroic defense for his friend Jabez Stone.

Daniel Webster defends Jabez Stone in front of the jury of the damned.

Daniel Webster’s defense is not just a battle for the soul of Jabez Stone but for the soul of the young American country. As they are setting up terms for the trial, Mr. Scratch reminds Webster just how important the devil is in America: “When the first wrong was done to the first Indian, I was there. When the first slaver put out for the Congo, I stood on the deck. Am I not still spoken of in every church in New England? ….Tell the truth, Mr. Webster – though I don’t like to boast of it – my name is older in the country than yours”. To the devil, he is as American as apple pie and has done more for America than Webster has ever or will ever do. Mr. Scratch’s argument that America is just as wicked as he is becomes stronger as he parades out his all-star lineup of early American dastards, liars, traitors, and knaves to stand as jury and judge.

Daniel Webster is given one chance to defend Jabez’s soul and the integrity of America (an interesting historical choice given real-life Daniel Webster’s involvement in the Missouri Compromise of 1850). While throughout the film American ideals have been alluded to, Webster’s defense explicitly praises the American spirit and its promise of freedom to all. Daniel Webster asks the jury to honor the America they once served and believed in by giving Jabez Stone his freedom. Ending his case Daniel Webster declares:

“Yes. We [Americans] have planted freedom in this earth like wheat. And we have said to the skies above us “A man shall own his own soul”… You can’t be on the side of the oppressor. Let Jabez Stone keep his soul, the soul which doesn’t belong to him alone but to his family, his son, and his country! Gentlemen of the jury, don’t let this country go to the devil! Free Jabez Stone. God bless the United States and the men who made her free”.

Daniel Webster’s plea to the American ideal of freedom succeeds in winning over the heart of the damned jury to save Jabez’s soul. Mr. Scratch is kicked out of New Hampshire and told to never return. Jabez makes everything better with his family and forgives the townspeople of their debts to him, joining with them in the newly organized farming union. While Mr. Scratch has left Stone’s small town of New Hampshire, he has no plans of leaving America. In the closing scene, Mr. Scratch breaks the fourth wall, searching the audience to find another person to strike a deal with to steal their soul.

Mr. Scratch finds his next victim among the audience.

Jabez’s tale isn’t a religious moral lesson reminding us to follow God or to choose love like Murnau’s Faust; The Devil and Daniel Webster seeks to reinforce old-fashioned, American ideals. Jabez’s downfall and all those Americans who had fallen prey to Mr. Scratch was the rejection of the principles inherent in the myth of America’s founding: hard work, religion, family, and egalitarianism. While Daniel’s climactic speech comes close to hagiographic American patriotism, the film surprisingly confronts some of America’s shortcomings. The capitalist greed of the Mr. Potter-like Miser Steven’s domination over the town’s farmers threatens to overwhelm the common man’s economic freedom. Mr. Scratch calls out America’s mistreatment of Native Americans, a rare admission in classic-era Hollywood. America’s achievements are further legitimized by the film’s willingness to include many of America’s blemishes, showing that if there is hope for someone like Jabez there will always be hope for the soul of an America that sticks to its morals.

Perhaps Dieterle picked this adaptation of the story on the eve of World War II to contrast with the Nazi regime he had fled a decade earlier and whip up American patriotism. Jabez Stone’s unification with his fellow farmers into a union-like grange foreshadows the collective spirit desired in America’s World War II homefront war time efforts. The film’s message to the United States is one of unity and perseverance in the face of evil, coming largely from within our own personal desires. The film reminds us that the devil is still at large roaming the American countryside seeking souls for collection. He is set to continue to play an integral part of America’s internal battle for its soul. This story could happen to any one of us.

Comparing German and American Fausts

Both Faust and The Devil and Daniel Webster are imaginative adaptations of the Faustian legend that create their own unique world. Both films employ various stylistic and aesthetic elements to shape the story around the filmmakers’ intended themes and messages. Every aspect of the film serves to remind its audience that this is not the story of one man’s fight against his demons but representative of the age-old battle of good and evil waged in the heart of every person. The large crowds and cleverly employed miniatures, the Biblical symbolism, and the theatric acting all work to build an elaborate, grand tale. Murnau’s Faust heavily leans into verbose, theatric acting so at home in silent films.

The Devil and Daniel Webster is much more restrained in its aesthetic approach. Jabez Stone’s story is not the manifestation of a battle between God and the devil but stands as a microcosm of America. Jabez’s rural New Hampshire town is full of everyday Americans wearing dirty overalls and long dresses instead of capes and hats adorned with feathers. The biggest spectacles in these farmers’ lives are Daniel Webster’s periodic visits to the town.

Bernard Herrman’s Oscar-winning score for Dieterle’s film incorporates American folk music such as “On Springfield Mountain”, “The Devil’s Dream”, and “Pop Goes the Weasel” fiddled by the devil himself to evoke the mythic spirit of early 19th century America. Large sets would be the antithesis of the film’s portrayal of a small everyday American caught up in the devil’s dealings. While the scale of the film might be much smaller than Murnau’s, Dieterle incorporates plenty of masterful cinematography. His manipulation of lights and shadows throughout the film would have made his fellow German-born Murnau quite proud.

A major difference between the two films is their portrayal of the devil. Both Mephisto and Mr. Scratch represent the things that each of the protagonist’s cultures fear the most and selfishly yearn for. Mephisto is the image of medieval European evil, an all-consuming power with mystical powers mimicking God’s own power. His Mephisto provides his victims unattainable eternal youth and an incessant amount of sex and orgies in an age of mass death and sexual restraint.

Jannings himself leans into the awesome power of the devil, rarely restraining his performance. He dances across the screen with his exaggerated devilish grin and flowing cape. (His role as the devil was good practice for when he would reprise the role in real life as a willing participant under the Nazi regime). Mephisto is out of this world, giving his victims a chance to deceive themselves into being a god of the earth with through the devil’s temporary power.

Left: Mephisto flying with Faust. Right: Mr. Scratch blends in with the townsfolk.

Unlike Mephisto, Mr. Scratch is more human than demon. While he does have immense power, he doesn’t show off by taking his victims on magic carpet rides through the night sky like Mephisto. When he presents Jabez with a pot of Hessian gold, Mr. Scratch simply kicks up a floorboard in the barn to reveal this newly conjured ancient treasure. Mr. Scratch blends in with the townsfolk, acting more like a citizen of the town than the prince of darkness. Walter Huston, in an Oscar-nominated role, exudes enormous amounts of confidence and devilish fun. He equally revels in his power when making his victims’ great men of renown and when he collects their souls mercilessly for eternity.

Mr. Scratch seems to be everywhere, pushing Jabez and others to reject their morals. Mr. Scratch promised power, social clout, and wealth in an age of egalitarian values, hard manual labor, and economic strife. While Mephisto visits Earth in a one-off bet to overtake all of humanity, Mr. Scratch lives among his victims, taking in a wide collection of politicians’ and everyday Americans’ souls. Mr. Scratch doesn’t plan on lording over humanity in the open; he is content to pull the strings behind the scenes by giving power to the richest and most powerful men in business, politics, and society.

Overall, both films are excellent examples of how a similar literary tale can be adapted and molded by the vision of filmmakers to draw out different themes and messages from the same story. Both films are also top-notch examples of different schools of filmmaking, Murnau’s Faust as an example of German Expressionism, and Dieterle’s The Devil and Daniel Webster as an example of classic Hollywood narrative filmmaking, and respective cultures and histories. With the endless possibility of cinema’s storytelling capabilities, the tale of Faust will continue to inspire inventive films in subsequent years and in various parts of the world to remind us of the dangers of human greed and selfishness.

My wife and I saw The Devil and Daniel Webster for the first time just last year. It shares a lot thematically with It’s a Wonderful Life, in that both are about the bad things that can happen to us when we forsake our everyday democratic values and the common man and woman. Walter Huston is very fun to watch and obviously enjoyed the role.

I’ve not seen Faust, but it looks from the screenshots like you could stop it arbitrarily at any point, blow up and print the frame, and have a work of art.

That’s an interesting parallel I haven’t thought of before between the two films. They even both have an extraterrestrial figure as a large part of the film. And Faust is definitely one of Murnau’s more beautiful films which is saying quite a bit.

I haven’t seen either film, but really enjoyed your review of them both. I’m fascinated by the Devil and Daniel Webster–I had always assumed that film was about his role in the compromise. I was obviously way off! The devil character in the second film sounds far creepier–but as you say, in real life, Jannings was the scarier of the two.

That would be a fascinating film in and of itself! He mentions the Missouri Compromise explicitly in the film as if it was a good accomplishment and I had to shake my head a bit. Daniel Webster really feels like such a random person to lionize but it was refreshing to see a different American than Abraham Lincoln.

Both films are fascinating and I learned much from your dissection of each.

During my most recent viewing of The Devil and Daniel Webster I noted that Anne Shirley’s character resembled Janet Gaynor in Sunrise. Was this a little nod from Dieterle to Murnau? -CaftanWoman

Thanks! Janet Gaynor’s and Anne Shirley’s characters really do have the exact same hair. It would interesting to know how much Dieterle was thinking about Murnau’s Faust at the time.