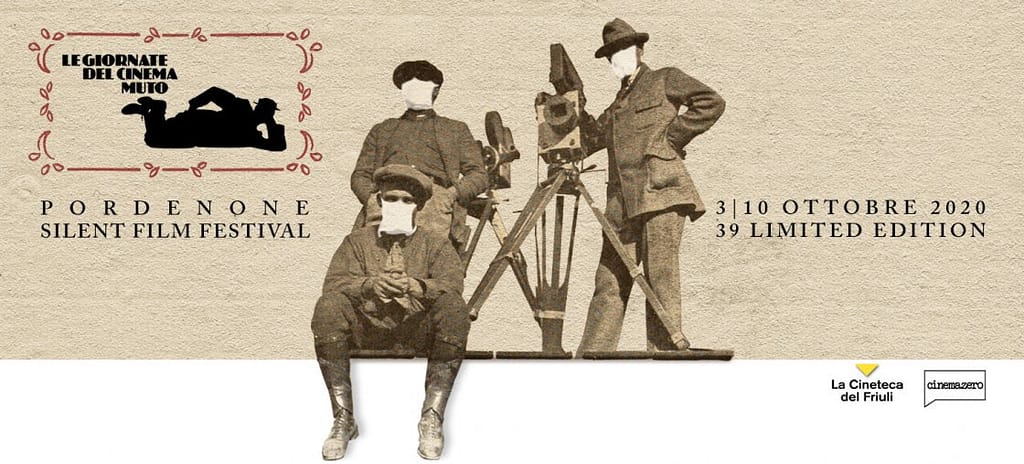

As a poor, young millennial on the verge of entering the full-time job market (if it still exists), I’ve never had the time or the money to attend any major film festivals. While earlier in the year I was planning on buying a short flight to volunteer at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, I would never have dreamed of being able to participate in Italy’s Pordenone Silent Film Festival. An online festival can in no way match the experience and community provided by an in-person festival; however, I’m grateful for the chance I had to watch these rare, diverse silent films which I couldn’t have done otherwise. It also motivates me to save up for attending the Pordenone and other film festivals in the future.

One thing I’ve learned from my online experience is how much effort it takes to schedule time in my day to be able to catch everything. Each time I missed an event or a film, I had a sinking feeling knowing that I might not get the chance to see that film for a long time. If it took a concentrated amount of effort to fit in a few hours each day, I can’t imagine how draining — and exciting — a full-day schedule would be like in person. I was successful in watching several of the book reviews and masterclasses by musicians and most of the post-screening discussions.

Since I was able to catch all of the feature films presented, I’ve listed my reactions and thoughts about each film, ordered from my least favorite to my favorite film. All of the films I saw were beautifully restored and even if a film didn’t quite click with me, I enjoyed myself and deepened my knowledge of the silent era with each new film.

National Customs 國風 (1935)

Li Lili and Luan Ringyu, two of the biggest stars in Chinese silent cinema, star as competing sisters in love with the same man against the backdrop of a modernizing China. Both stars are engaging, especially Lili playing a modernized woman who causes a scandal when she wears makeup (gasp!). The story itself is overly melodramatic and more interested in conveying its propaganda New Life Movement message than in developing well-fleshed-out characters. The most interesting aspect of National Customs was its unique look into the culture and political landscape of Chang Kai-Shek’s China in the 1930s. I was impressed by much of the cast and look forward to seeking out more Chinese silent films (I hear Ringyu’s The Goddess (1934) is a must-see).

Where Lights Are Low (1921)

Sessue Hayakawa plays the Chinese prince T’Su Wong Shih who rejects his royal status to marry his sweetheart Quon Yin, the daughter of a common gardener played in yellowface by Gloria Payton. After Quon Yin is kidnapped by human traffickers in San Francisco, Wong Shih must work odd jobs to collect thousands of dollars and fight gangsters to buy her freedom back. The film includes quite a bit of action, including a frenetic, exciting climactic fight between Hayakawa’s character and the head gangster Chang Bong Lo, played by Togo Yamamoto.

The biggest disappointment of the film was Gloria Payton’s performance as Quon Yin, whose yellowface and uninspiring acting made it hard for me to be fully invested in her and Wong Shih’s love and relationship. Luckily, Hayakawa and fellow wonderful Japanese actor Togo Yamamoto inject the much-needed energy into the film to make it exciting, if not sometimes formulaic, entertainment.

Kill or Cure, La tempesta in un cranio (1921)

This Italian film was perhaps the most unique and unusual film of the festival. Carlo Campogalliani plays a man who is deathly afraid that he will soon go insane because of his ancestors’ history of insanity. His friends take matters into their own hands to prove his sanity unfounded. In many aspects, Campogalliani’s film persona is similar to many of Douglas Fairbank’s 1910s characters, sharing Fairbank’s playfulness and athleticism when facing surrealist situations (The Mystery of the Leaping Fish would be a great short to precede this film). For most of the film, you don’t quite know whether the events are actually happening or merely the results of the main character going insane. While sometimes this ambiguity can drive you mad, that’s part of the charm of the film and is where much of the film’s best comedic touches come from.

Unjustly Accused, Ballettens Datter (1913)

In the early 1910s, Denmark was the king of cinema. Unjustly Accused showcases the concise stories, dynamic framing, and beautiful sets that Denmark’s most prolific studio Nordisk was known for. The filmmaking is top-notch throughout even if the story itself is a little bit underwhelming. A ballet dancer falls in love with a count who agrees to marry her if she will leave the stage. After the count finds that his wife went against his wishes secretly, he duels the theater manager, the man he thinks is having an affair with his wife. For modern viewers, the husband’s misogynistic behavior turns him into the villain, making it hard to see why the ballet dancer would ever want a relationship with him in the first place. While we’re disappointed that the husband does not quite learn his lesson and the couple’s relationship problems never are completely solved, we are satisfied with the twist that comes with the film’s final duel scene.

A Romance of the Redwoods (1917)

A Romance of the Redwoods features two titans of early Hollywood cinema, Cecil B. DeMille and Mary Pickford. Pickford plays an orphan who moves west to live with her uncle. Upon her arrival, she finds her uncle dead and an outlaw (Elliot Dexter), who she naturally falls in love with, having taken her uncle’s identity. The film manages to develop the characters’ romance without it devolving into an overdramatic “good woman changes bad man” trope. Dexter is a bit wooden in the film as a flawed man with little hope of reform but Pickford’s strong persona, alongside a fun turn from a rejected suitor played by Charles Ogle, buoys the film. Pickford even gets to play the role of heroine, saving the day by outwitting the dozens of rough and tough frontiermen.

Penrod and Sam (1923)

If any classic director unfairly gets a bad rap, it’s William Beaudine. While many know him as the B-director of such oddities as Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla, Beaudine’s silent career has been largely overlooked. Penrod and Sam shows Beaudine’s ability to capture idyllic scenes of Americana and his penchant for working with young actors. This coming-of-age tale features excellent child actors and never falls into cheesy or melodramatic territory. Another bonus of the film is the two African American children in the friend group who are represented largely without racial stereotypes or caricatures, sadly a rarity in many American films of that time.

The Brilliant Biograph (1897-1902)

It seems like every month or so someone posts a clip of an early film with added color and inserted frames that didn’t exist in the original print. This compilation, a collection of early Biograph films recently restored by the EYE Film Museum, proves that these early films need no embellishment to enchant modern audiences, just a proper restoration. From snapshots of famous locations to the filming of everyday activities, these early films provide a window into a forgotten world of yesteryear while capturing the magic and potential of a nascent media. Watching an hour straight of these over-century-old short films, some even with hand-drawn color, brought out the variety and inventiveness of these early actualities and got me excited to watch more 19th-century films.

The Apache of Athens, Oi apahides ton Athinon (1930)

This was the biggest surprise of the festival for me, a proto-neorealist picture filmed on the streets of Athens. The film follows a tramp, warmly called “the Prince” by his friends, who is caught between two girls, one a working-class woman and another the daughter of a rich Greek oligarch. A fascinating aspect of the film was the songs used for the film. Since the film was originally released with sound-on-disc technology, restorationists added several songs with lyrics into the film. These classic Greek songs helped to add to the atmosphere of this Greek film and build the romance of the two leads that never felt like a marketing ploy for selling sheet music. The music, the realistic amateur acting, its touches of humor, and the on-location shooting of Greek ruins make The Apache of Athens a lovable classic of Greek cinema.

The Devious Path, Abwege (1928)

The Devious Path is one of G.W. Pabst’s smaller, lesser-known pictures sandwiched between his better-known works, a year after The Love of Jeanne Noy and a year before Pandora’s Box. Brigette Helm plays the wife of a lawyer who, after being cooped up in the house and unsatisfied with her marriage, decides to seek some freedom and find some excitement. The film is a household drama confided to unassuming homes and everyday locations, perhaps except for an exotic nightclub. Pabst beautifully uses shadows and different lighting set-ups to convey the mood of the characters, representing the inner turmoil and dissatisfaction of the main characters. Although marital infidelity plays a central part in the plot, the film works so well because it focuses on the wife’s desires and feelings and withholds judgment on her and her husband. The lack of a didactic moral lesson (despite the poor English translation of the German title), Pabst’s steady direction, and Helm’s energetic performance made The Devious Path the gem of this year’s festival.

Overall, the festival delivered on its promise to provide a diverse palette of great silent films from around the world. Even though the festival is over, many of the post-screening discussions are available at Le Giornate del Muto YouTube channel. I’m excited for the free films from past festivals that will be available on the Silent Stream in the upcoming months which will doubtless keep me excited for the 2021 festival.